A recent visit to the African Record Centre in Brooklyn’s Little Caribbean Cultural District allowed Radhya Kareem, MS Historic Preservation ’24, to deepen her understanding of the neighborhood’s musical history.

“The African Record Centre shows how African music was brought to New York and Brooklyn,” she said. “It’s this distinct site in the neighborhood but also a realm within culture that’s sort of intangible, because, although it resides in space, music is not really about buildings.”

Kareem’s visit was part of a neighborhood tour for the “Little Caribbean Cultural Resource Survey” community engagement course taught by Dr. Sophonie Milande Joseph, adjunct associate professor in the Graduate Center for Planning and the Environment. In the class, students in the Historic Preservation and Urban & Community Planning programs researched the history of the Little Caribbean community in Brooklyn, which encompasses a spacious area between Brooklyn College in Flatbush and the Brooklyn Museum near Prospect Park and is home to the largest and most diverse Caribbean American population. The students also engaged with other important sites in addition to the African Record Centre and learned what it means to preserve something as dynamic and alive as a community that’s continually evolving and includes many intangible elements.

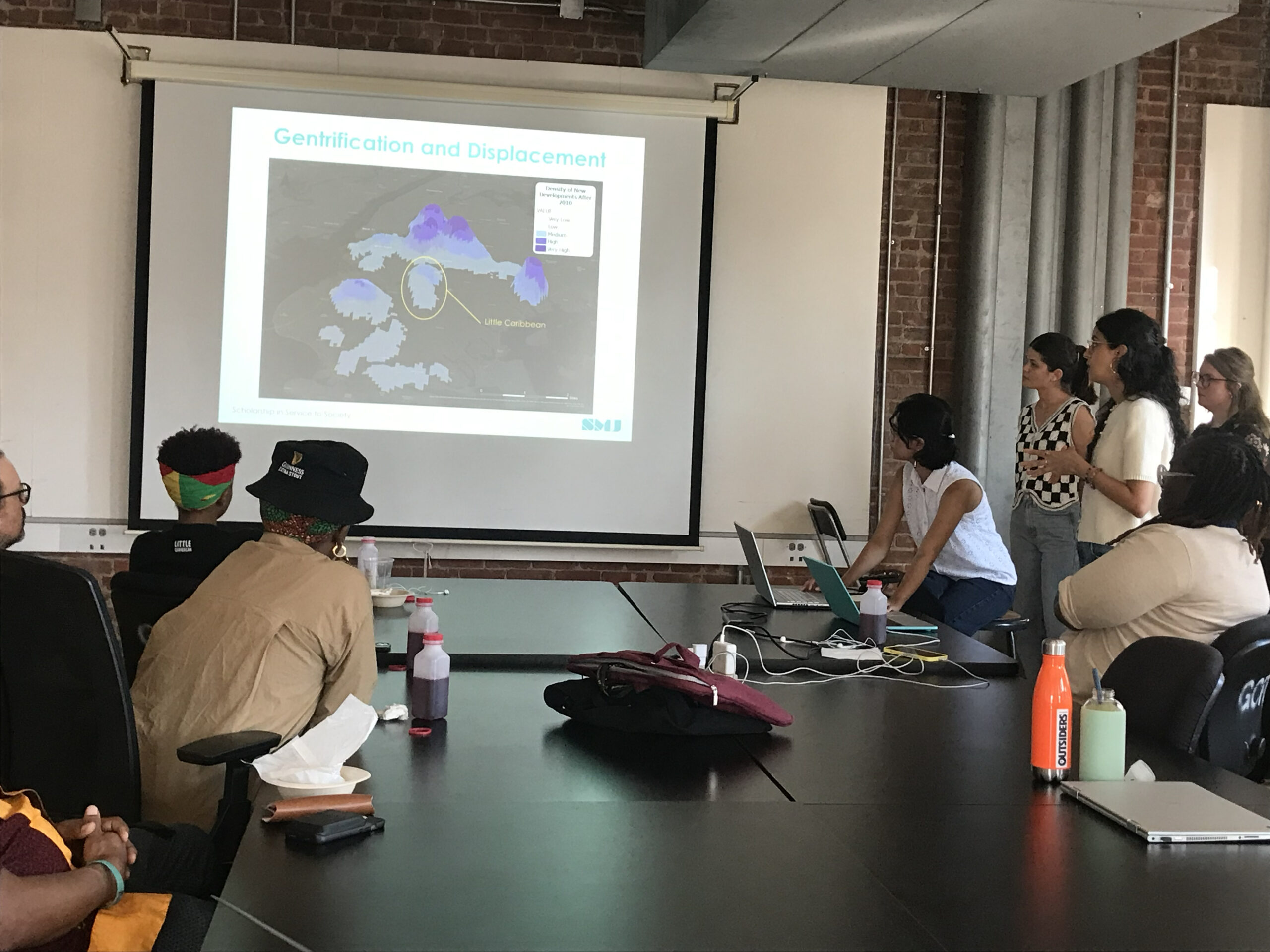

Over the course of five immersive weeks, they worked alongside local community nonprofits to research culturally significant sites within the Little Caribbean community as part of a larger effort to pursue future listing in the National Register of Historic Places. Inclusion would help to mobilize public and private support and funding for historic preservation of the neighborhood’s buildings and cultural practices, in turn mitigating the displacement of longtime residents and legacy businesses caused by decades of gentrification throughout Brooklyn.

In 2017, Shelley Worrell, cofounder of caribBEING, planted the seeds of this effort when she campaigned for the NYC Mayor’s Community Affairs Unit to officially recognize Brooklyn’s Little Caribbean neighborhood.

The neighborhood has a vibrant and thriving cultural landscape, with boutiques, restaurants, beauty salons, cultural centers, and businesses that bring together unique strands of Caribbean life as well as the West Indian American Day Carnival that attracts revelers to celebrate the richness of Caribbean culture each year.

The Historic Districts Council received funding from the Preservation League of New York State and the New York State Council on the Arts, and hired Joseph to work with Little Caribbean, Inc., and caribBEING to conduct a cultural survey of the Little Caribbean neighborhood. As part of the grant’s scope, Joseph’s team will create a Multiple Property Documentation Form (MPDF) that identifies and establishes the cultural and historical significance of key businesses, infrastructure, and traditions of Little Caribbean for the nomination process for the National Register of Historic Places.

“The cultural resources survey of the Little Caribbean neighborhood led us to learn about the greater New York immigrant experience,” Joseph said. “The idea of doing a research survey in this context is new. There was a lot of comparative research that we did with other immigrant groups in the city. We looked at the Little Dominican district, Little Guyana, Spanish Harlem, and other ethnic enclaves to learn what they’re doing to preserve their communities.”

“We had to go into the archives to get logs and maps of the past so we could document changes over time,” she said. “We were doing research across themes of culture, education, and public service, while trying to look at the community holistically in order to assemble different facts into a chronological timeline and coherent story.”

For Ashley Adams, MS Historic Preservation ’24, the studio demonstrated the importance of centering communities during historic preservation efforts.

“Shelley took us on a walking tour of the neighborhood and we met with different local shop owners,” said Adams. “She highlighted the places of importance in the neighborhood both historically and more recently because of the Caribbean immigrants who are coming in, like the Labay Market, whose owner imports all of his produce from his farm in Grenada.”

Adams grew up in Trinidad and finds solace in the Little Caribbean neighborhood, where she’s able to find shops, restaurants, and places of community that remind her of home, especially when she walks along Nostrand Avenue.

“Designating Little Caribbean as a historic district for its cultural significance will hopefully help prevent further gentrification in whatever form it takes, and help preserve a sense of place for the people who live there,” said Adams, who’s applying what she’s learned in the studio to her thesis project that focuses on uplifting local histories in Trinidad through the preservation of gingerbread houses and examination of policy to protect built heritage.

Kareem said that the studio focused on understanding the context and history of Little Caribbean through the eyes and ears of community members. The students listened to what people had to say about their lives, as well as different aspects of the local culture such as festivals, music, and cuisine.

“Something that I really appreciated about Joseph is that she suggested that we don’t just enter the community as outsiders but that we work with community partners and ask them to guide us on how to navigate the area,” Kareem said.

Kareem is now a student assistant for Joseph, along with Olivia Holland, MS Historic Preservation ’24. The team is continuing to research the historical record, interviewing Little Caribbean community members, creating visual assets for the community, developing a neighborhood context statement, and designing a survey so the community members can document, from their own perspective, current and historic heritage. This will culminate in a final report on these research findings to be given to the partners.

In particular, Kareem is delving into Little Caribbean’s musical history, i.e. its sonic genealogy, learning how different strains of music and dance emerged and evolved in the islands over time and were brought to the neighborhood.

“Something interesting that I learned about is a genre called Chutney Soca, a hybrid form of Soca that originated in Trinidad and Tobago and contains South Asian influences of Indian Chutney Music,” she said.

Kareem appreciates how Pratt’s Historic Preservation program provides a global perspective, shedding light on how communities in both New York and beyond have managed to safeguard their built environment and culture. A trip she took to Cuba as part of a Historic Preservation Documentation course influenced her thesis project, which examines how her home city of Karachi can better assess changes in the built fabric that have cultural meaning. The Little Caribbean project, meanwhile, has shown her how communities themselves can shape narratives around their past, present, and future, a message that Worrell emphasized in their meetings.

“All of this work is really about preservation and sustainability, ensuring that our community has its place in New York City for generations to come,” Worrell said. “It’s really important for us to claim our seat at the table and to create and preserve spaces that are relevant to, in our case, Caribbean communities.”

Joseph emphasized that engaging with community partners such as Little Caribbean will be an ongoing and central part of the project’s final phases.

“They are placemakers,” Joseph said. “We should see our neighbors as our colleagues who have a multidisciplinary approach to their work. They have ongoing programming and we can support them by attending their events and engaging with this intentional community-based development.”