More than two dozen New York City neighborhoods are considered “food deserts,” places where it’s difficult to get fresh fruits, vegetables, and groceries. For children living in these areas, inadequate access to nutritious food can lead to health problems and make it hard to learn in school.

This past fall, a group of Pratt undergraduate students worked with the community-based nonprofit Harlem Grown to imagine ways to enhance access to nutritious food for families near two urban farms located in food-scarce neighborhoods. In Harlem Grown: Cultivating the Urban Food Desert, a studio taught by Visiting Assistant Professor of Interior Design Charles Newman, students investigated the spatial, infrastructural, and technological challenges faced by Harlem Grown and worked with them to improve their sites.

For more than a decade, Harlem Grown has transformed vacant lots into agricultural hubs, learning centers, and community gathering spaces, but resource pressures such as lack of reliable access to water and electricity, along with an absence of expensive amenities such as cold storage units, have limited its ability to expand.

“The studio let students grapple with real-world complexities,” Newman said. “We had an external partner that put forward a series of constraints and desires and had a history that we needed to understand. From there we needed to work together to define a path forward.”

Throughout the course, Newman emphasized the importance of community participation, transparent processes, and interdisciplinary collaboration, and encouraged students to consider a range of questions. How would their designs enable Harlem Grown to better serve the wider Harlem community? How would their work help children who spent their afternoons and weekends at the community gardens excel and grow as citizens of their community? How could they develop brainstorming workshops that included and empowered the participants?

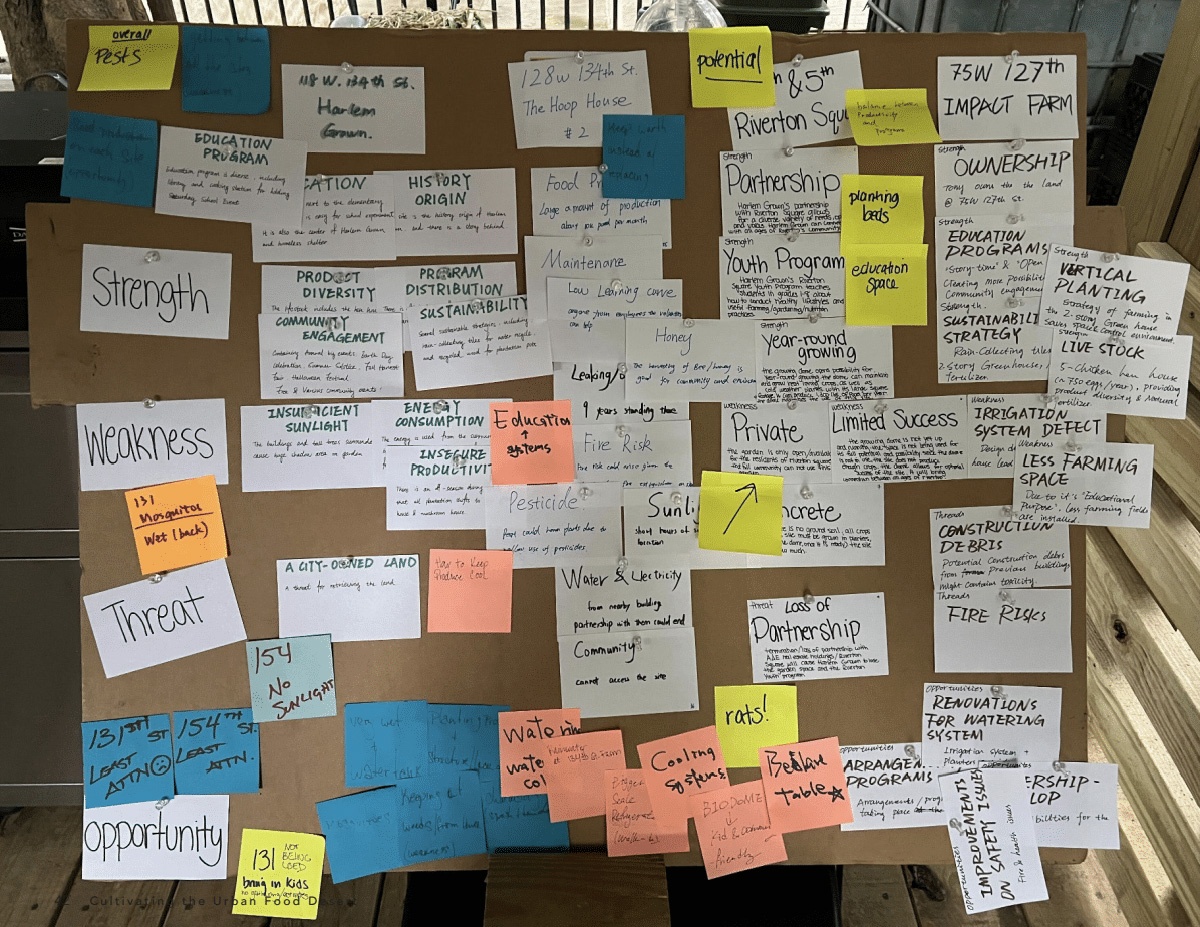

After studying how food deserts affect communities, the class fanned out across Harlem Grown’s 13 agricultural sites to take notes, ask questions, and get a sense of the work to be done. They learned about the different kinds of fruits and vegetables being cultivated, egg and honey collection programs, as well as the various community activities hosted at each site with an assortment of neighborhood partners. They also assessed spatial limitations and possibilities presented by existing infrastructures such as greenhouses and irrigation systems, documented sunlight and weather conditions, and created maps and diagrams for future planning.

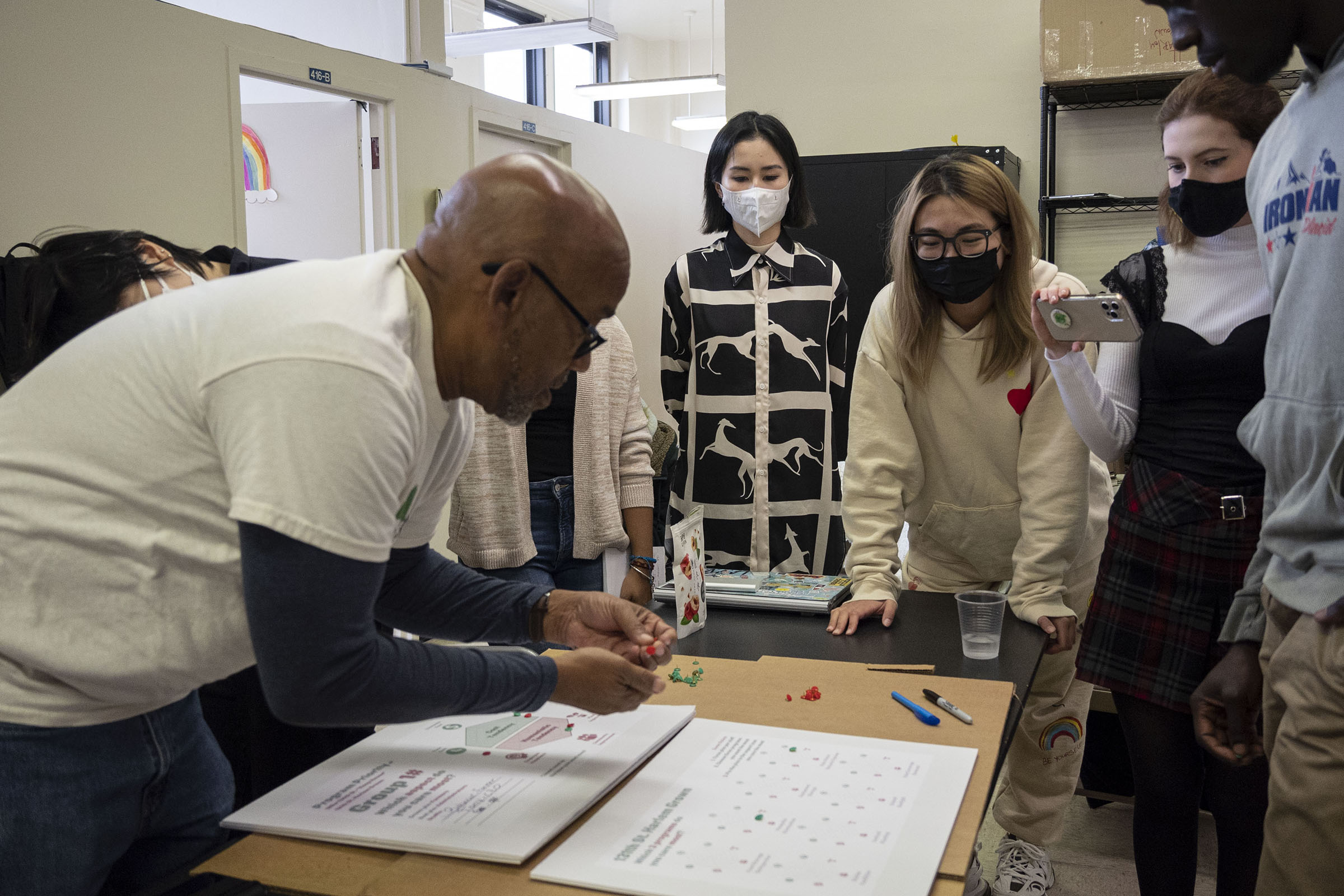

The students then designed a series of workshops to elicit feedback and insights about pain points and areas of interest from the Harlem Grown team. For some of the workshops, Harlem Grown members were given site plans and scaled “game pieces” representing different possible interventions such as a vegetable grow bed, a library, a water point or a gathering space; and were tasked with creating compositions for comparison and discussion. Limited resources and spatial constraints meant they had to prioritize only the most salient renovations. This allowed students to gain a clearer picture of what the Harlem Grown wanted and how to best fulfill their vision.

Gigi Huang, BFA Interior Design ‘23, said that the workshops helped her understand the conflicts that can arise when various stakeholders “go back-and-forth in the design process.” “Communication is an essential skill,” she learned, when navigating a range of viewpoints and accommodating different interests.

“I’m going into architecture school later this year,” Huang said. “I think this studio has really benefited me a lot because I started to think about design through a perspective of architecture and then I was also introduced to this community driven design process.”

The workshops and brainstorming sessions ultimately led to two sites being chosen for the final project. Two groups of students created design proposals for Harlem Grown’s 131st Street site, while two focused on the 134th Street site.

The teams drew on the practical and theoretical skills they had developed in the Interior Design program, making use of diverse building materials and technologies, sustainable design methods, and a growing appreciation for how design can facilitate human movement and behavior.

The first 131st Street group, consisting of Owen Zhao, Linwen Ni, and Jessica Kraemer, addressed water shortages by designing a rainwater recycling system and pond. They also envisioned a library, gathering spaces for community events, and secret nooks for children to play.

The second 131st Street group, consisting of Rebecca Chen, Selina Gong, and Kission Xiong, imagined an open space with ample seating, vertical planters, solar panels, and vegetable trellises to foster a continuous sense of flow. They, too, included rainwater collection mechanisms and a pond.

The two 134th Street groups had to consider different variables such as a greenhouse and a beekeeping program. Both focused on increasing the greenhouse’s yield, optimizing electricity and water usage, and creating spaces for the community to gather and learn about the agriculture taking place. Redesigned apiaries featured in both proposals to ensure that bee colonies survived through the winter.

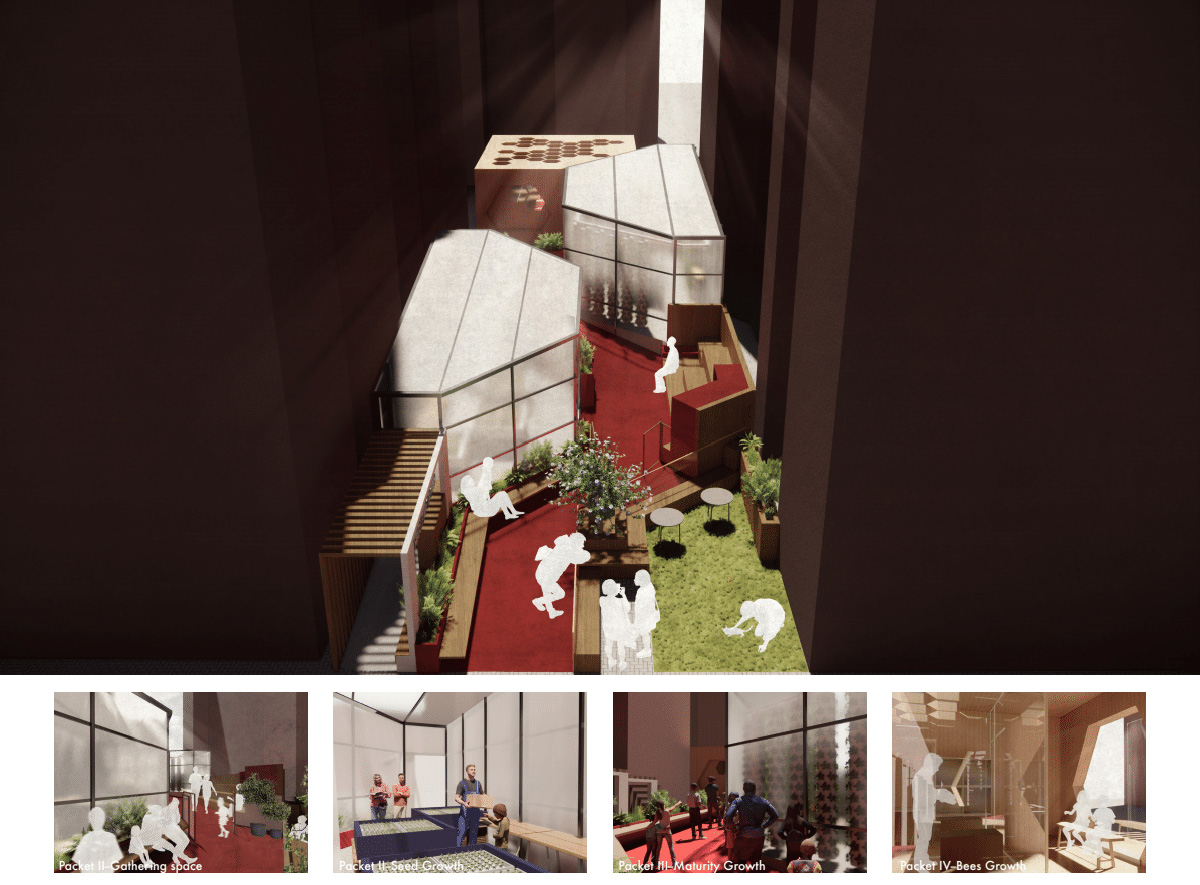

The first group for this location—Mackia Zhu, Azul Castillo, and Ningduan Yang—proposed a multi-tiered structure that allows for vertical gardens sustained by irrigation and airy rooms for education. The second group, consisting of Gigi Huang, Gloria Yu, and Tianyi Peng, imagined a sleek and rhythmic layout of greenhouses, gardens, and sitting areas that leads to a new apiary.

“It’s a really narrow space in between pretty high buildings,” said Huang, who worked on one of the 134th Street redesign proposals. “So we were just thinking about the direction of the sun and the heat energy, how the layout will make people feel safe and attract them to engage more with this farm, and how to make the greenhouse more welcoming from the outside.”

All of the student groups incorporated Harlem Grown’s guiding philosophy: to grow healthy children through urban farming. As a result, the design proposals are rife with ideas for building and fostering community, in addition to ways to increase food production.

“After collaborating with Professor Newman’s class to re-design some of our sites, Harlem Grown’s team has a renewed excitement about the creative ways that we can restructure our spaces to be more beautiful, produce more crops, and facilitate learning,” said Charles Maher, chief operating officer of Harlem Grown.

The studio’s final product—a 110-page book—captures the months-long design process with extensive imagery and design proposals. Moving into their careers and further academic growth, the students will be able to draw upon the lessons of this studio, while Harlem Grown will have a printed resource that it can use to seek out new opportunities and imagine future possibilities.