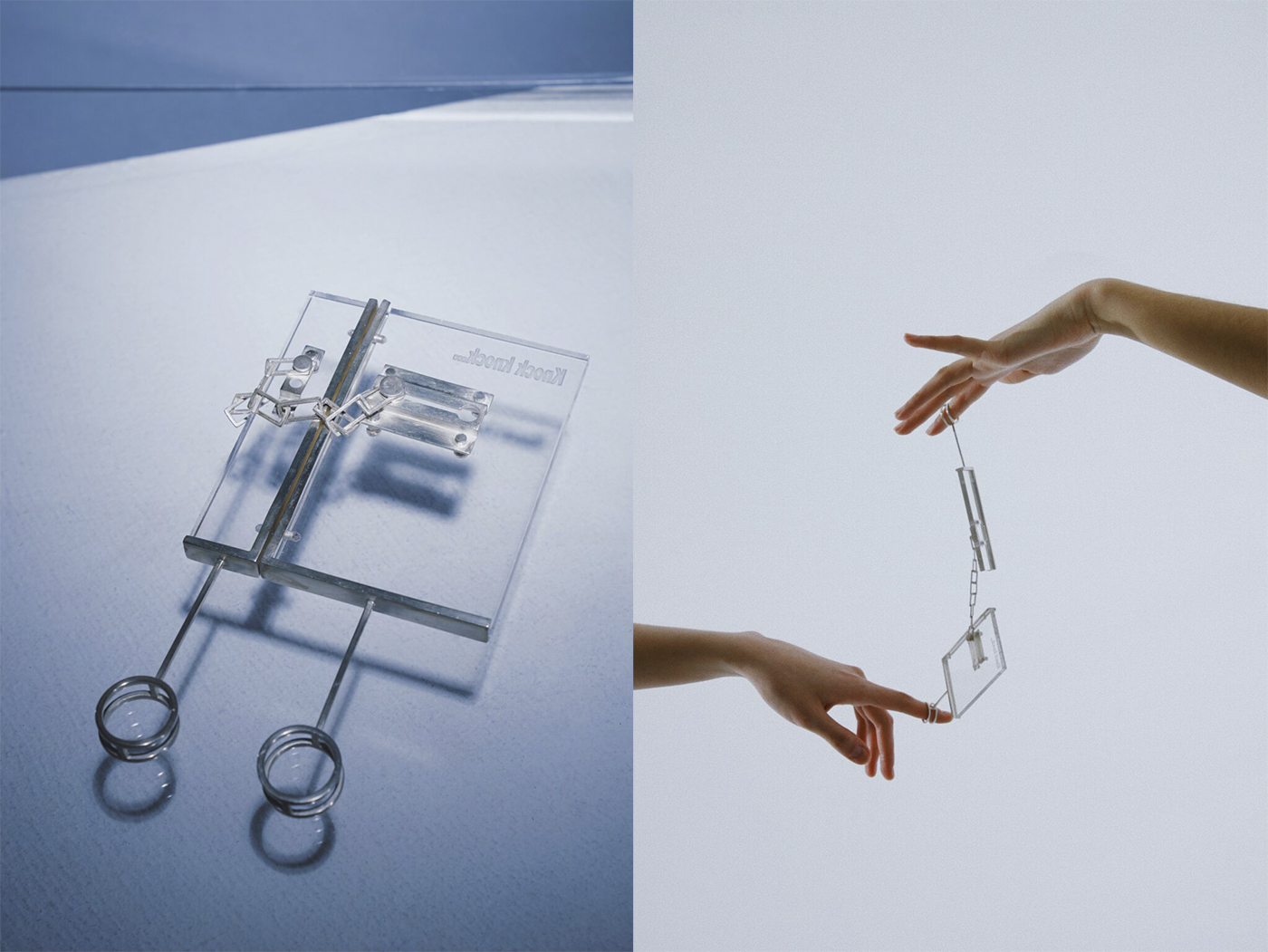

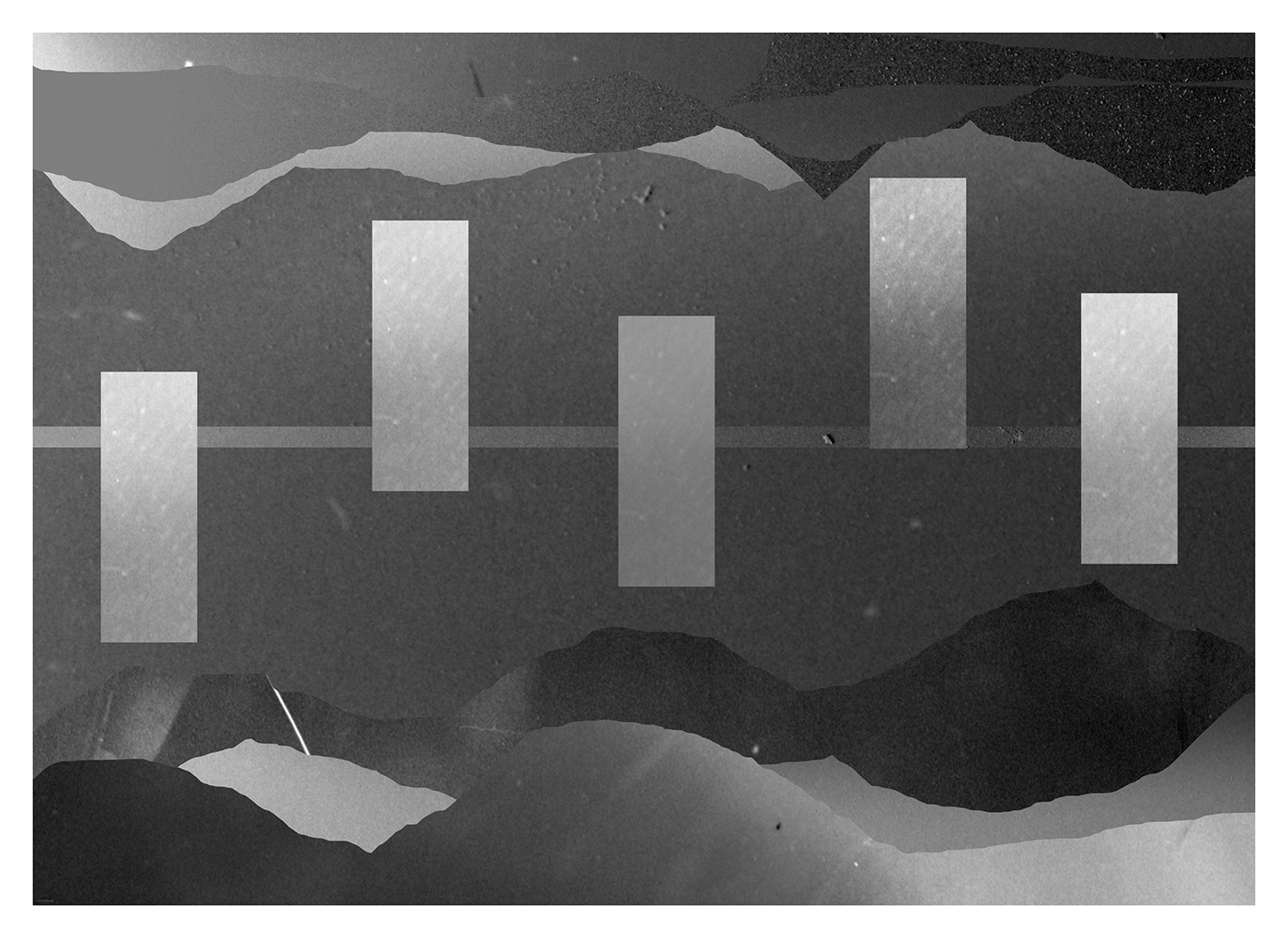

Work by Xiaoqing Rong, BFA Fine Arts (Jewelry) ’21, from the collection “Rebuilding the Verification of Existence”

The ongoing pandemic has changed everything, from the way we learn and create to how we think about the future. At Pratt Institute, students have used their creativity to adapt to these shifts, while addressing isolation, grief, uncertainty, hope, and community into their work. Eight of these students shared how their processes evolved over the past year and what they will carry forward into their future practices.

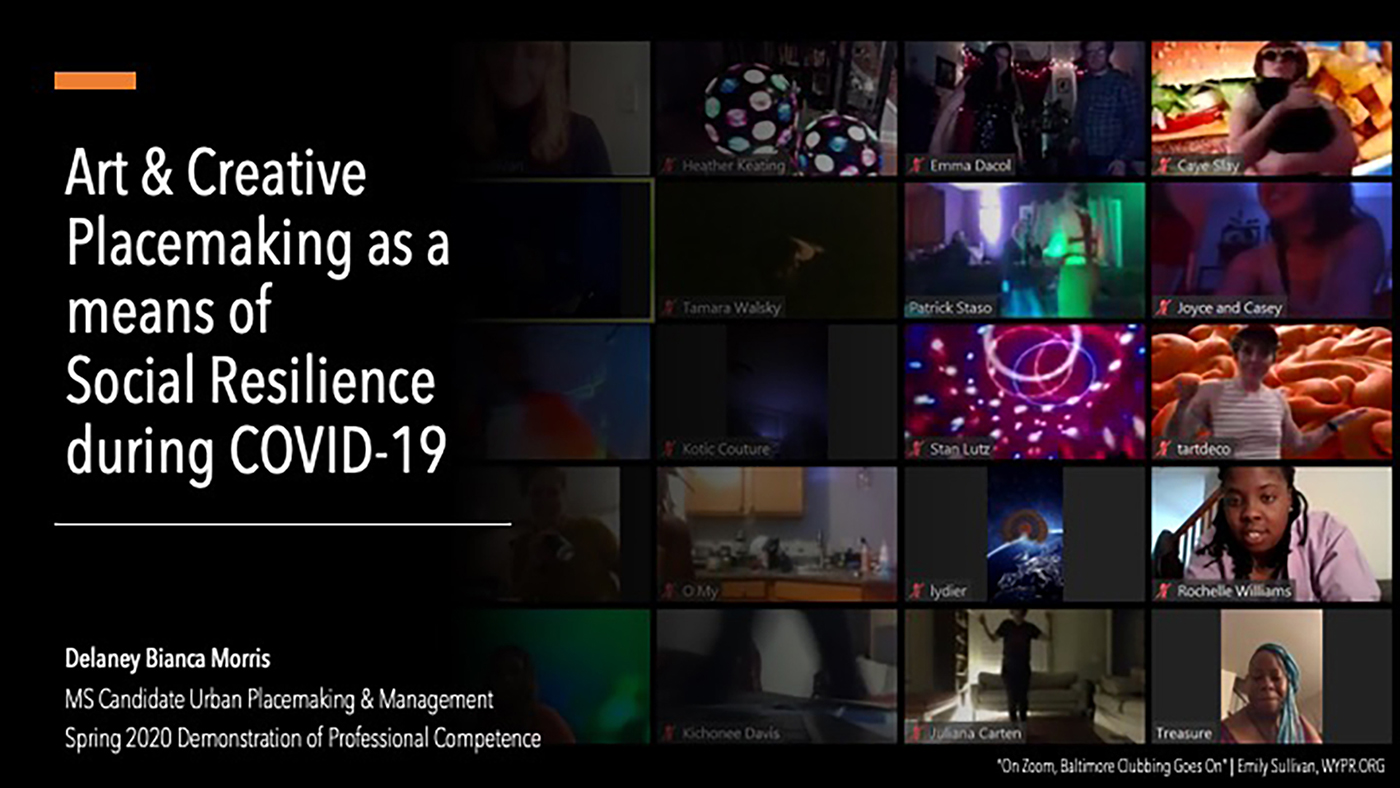

Before she arrived at Pratt, Delaney Bianca Morris, MS Urban Placemaking & Management ’20; MS Sustainable Environmental Systems ’21, was traveling across the country to perform with community samba groups and produce large-scale events like parades and music festivals. The lockdown measures and limits on in-person gatherings caused her to reevaluate how the arts and entertainment could be presented in public space.

“I shifted gears on my final Demonstration of Professional Competence and decided to highlight how the arts and creative placemaking had come alive in this new virtual reality,” she said, an approach that included everything from online music performances to the cross-collaboration between artists on Zoom. She also enrolled in another Graduate Center for Planning and the Environment (GCPE) program—Sustainable Environmental Systems—to position her work at the intersection of culture, urban planning, and climate change.

June 2020 presentation on “Art & Creative Placemaking as a Means of Social Resilience During COVID-19” by Delaney Bianca Morris, MS Urban Placemaking & Management ’20; MS Sustainable Environmental Systems ’21

“Over the last year, my biggest takeaway is that the world is so much smaller than we all thought,” she said. “One thing I hope continues is the community surrounding the arts that has connected online. The arts pivoted so quickly to adapt to the world, quicker than a lot of institutions and governments. I’ll carry forward with me the knowledge that even during a moment of panic, where I can feel so far away from my community, that in reality they are so close.”

Xiaoqing Rong, BFA Fine Arts (Jewelry) ’21, decided to stay in New York even as many of her friends left the city. She channeled the challenges of the past year into her thesis collection “Rebuilding the Verification of Existence,” using it as a space to process her experiences of isolation and loneliness and work towards self-acceptance.

“I visualized these negative emotions in wearable objects, making the feelings touchable,” she said. “The ‘self’ in this collection includes not only me but also other people in similar situations. By touching on these negative feelings, we ground ourselves in the world, assuring ourselves that we can exist in different ways. It also explores who we are and where we belong.”

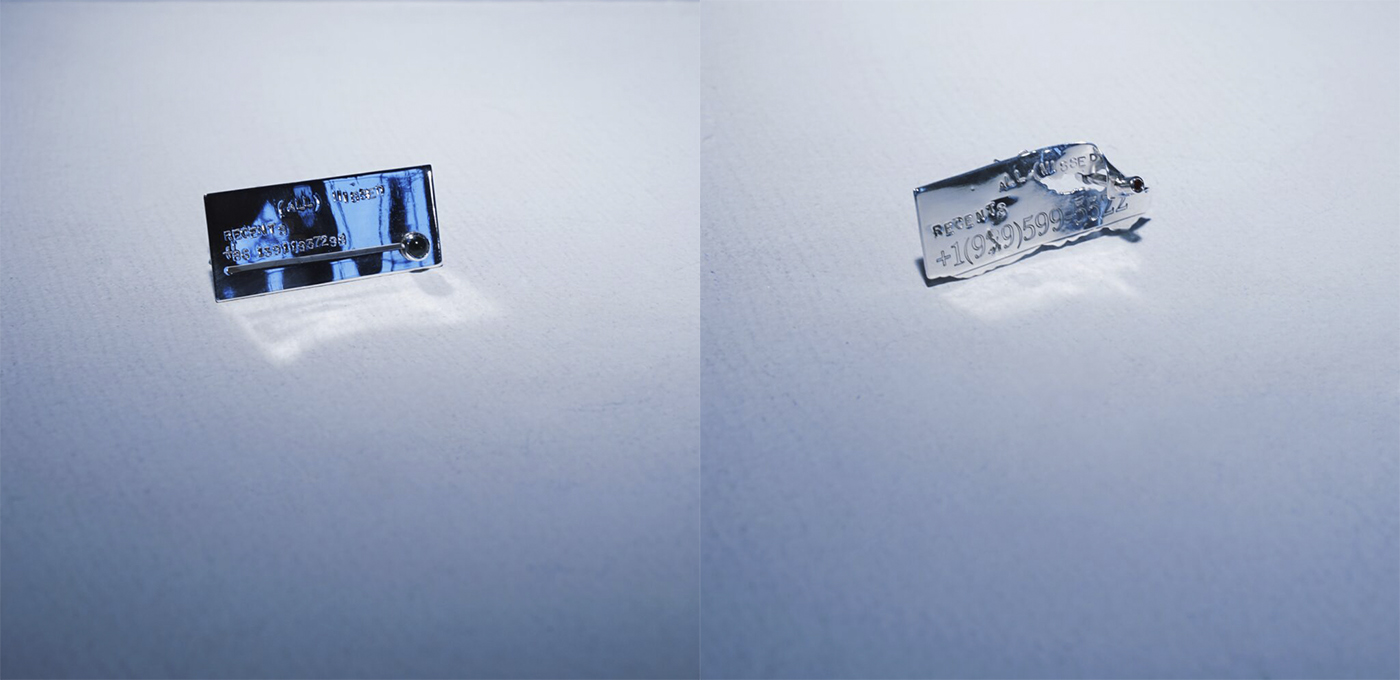

Work by Xiaoqing Rong, BFA Fine Arts (Jewelry) ’21, from the collection “Rebuilding the Verification of Existence”

Each piece in the collection has a fragment of life, like a recently dialed number on a silver earring and a miniature door chain connecting two pieces of acrylic that are attached to two rings, allowing them to be linked or separated.

“I think this collection could be my starting point in building my jewelry artistic style,” Rong said. “These traces of life bring these nostalgic feelings of having a connection with someone or something. Creating an emotional communication between the wearers, or viewers, and my jewelry has always been my key intention during the design process.”

Eleanor McGuirk, BFA Fine Arts (Drawing) ’21, processed the experiences of suddenly returning home, and the feeling of her plans being interrupted, into her work. “At first I felt disoriented and was unsure of how to continue my art practice,” McGuirk said. Soon, though, she found herself adjusting her approach to art, including to the smaller scale of working from home. “I found when I made these small yet very consequential changes, my art practice flowed better and became more enjoyable. Working on my childhood desk was fun and very doable after all.”

Eleanor McGuirk, BFA Fine Arts (Drawing) ’21, “Amaryllis- Strength, Borage- Courage, Laurel- Victory” (2020), watercolor, colored pencil, and acrylic, 9 x 12 inches

Her thesis show Idols features vibrant illustrations of older women in mythical and symbolic environments, reflecting her anxiety of losing time due to the pandemic. Through these pieces, she reconsidered the timeline for success and creativity and the value that is put on youth over maturity, particularly for women.

“Art was a certainty in my day and something I could rely on,” she said. “Not only was the subject matter of celebrating older women dear to me, but I also took influences from many different art and design styles. Researching these influences and rigorously planning out my pieces, I got to learn more about things like Thai architecture and Guatemalan textiles. I want to continue to feel that making art is an oasis of peace and opportunity for mindfulness.”

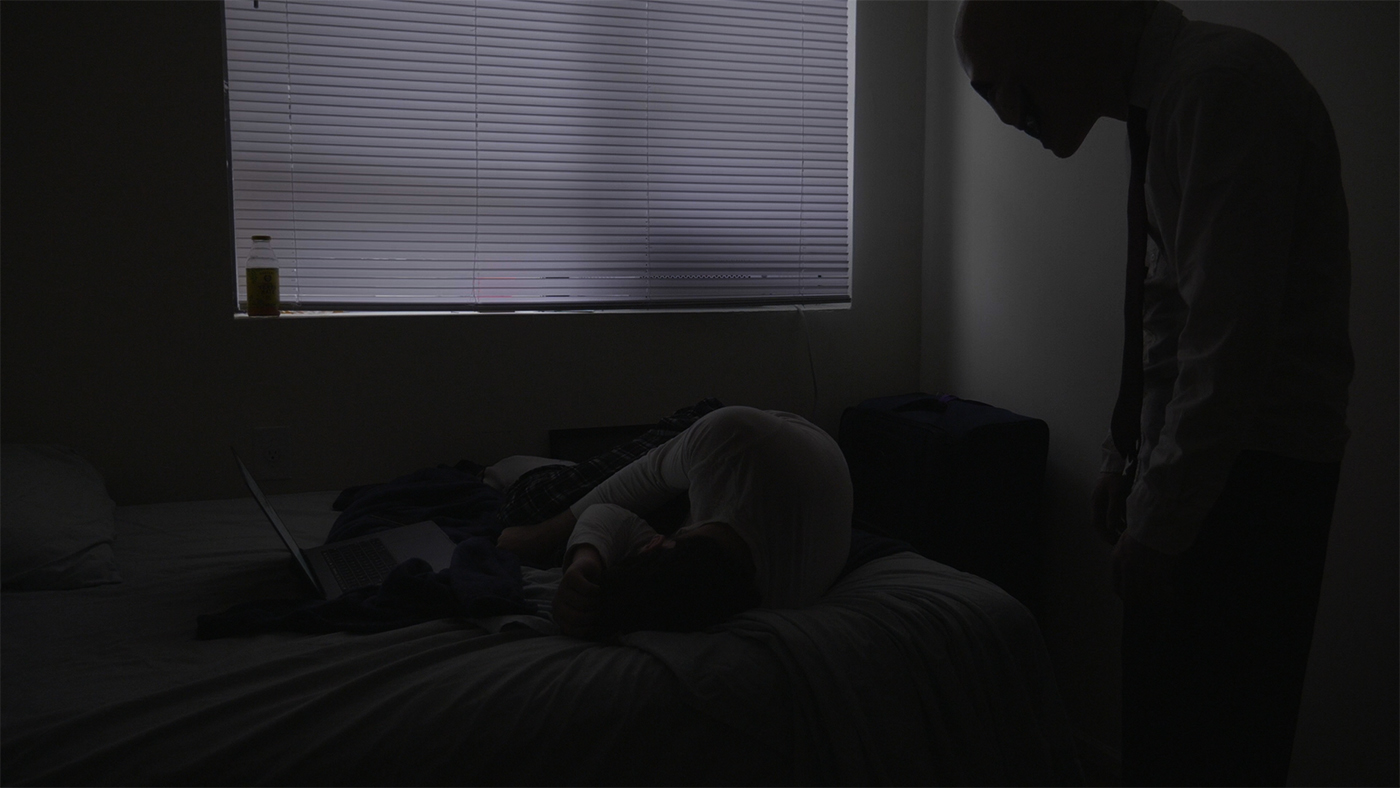

Ryder Hall, BFA Film ’22, similarly found in his work a way to confront the challenges of the past year while adjusting his creative process to more experimental films. His film 336 follows a recent college graduate who arrives in a new city under lockdown, spending two weeks quarantining during which he’s beset by strange masked entities. “I have been exploring how to be self-sufficient with making small-scale content,” Hall said. “Since last March I’ve been exploring abstract video distortion programs and rotoscoping to try and discover my own, independent style.”

Still from ‘336’ by Ryder Hall, BFA Film ’22

The pace of creating during COVID-19, with all its demands of safety and logistics, led him to creative solutions like character masks that covered their CDC-compliant face coverings and areas of the filmmaking process he hadn’t previously engaged in. “Before the pandemic, I used to be a lot more guerrilla with my filming tactics, but since we have to be so methodical to ensure everyone’s safety I learned to like producing,” he said. This included taking the Producing for Film class led by Film/Video Department Acting Assistant Chair Eric Trenkamp. “I found a way to utilize pre-production that works for me and isn’t just like a homework assignment.”

Yi-Ting Hsieh, MFA Interior Design ’21, also experienced a shift in her approach to her work, as her usual sources for inspiration, which had been going to new places, changed. “Maybe it was because of the lack of stimulation, but those few experiences when I went out to museums or visited new architecture all gave me profound experiences,” Hsieh said. She started to look at the places around her differently and consider how their interior designs could be more flexible.

“Blue Hill Pause” by Yi-Ting Hsieh, MFA Interior Design ’21

In the interior design studio on “Food Space” led by Professor of Interior Design Jon Otis, Hsieh brought this new perspective to a project on adapting businesses to sustain themselves through the pandemic and beyond. Her “Blue Hill Pause” project—which used the Blue Hill restaurant as a case study—focused on rebuilding relationships with food while elevating health and safety. “Before the pandemic happened, no one thought about whether we needed to adjust ourselves to this type of living, and even when it happened, most of us thought it would end in a few months,” Hsieh said. “When we got to the end of our projects, we acknowledged that this situation might go on longer than we thought. So I started to understand that as an interior designer you have to adjust yourself to any changes.”

Several students in Art in the Time of a Global Pandemic led by Carrie Schneider, visiting associate professor of photography, also reconsidered how they are approaching their practices. The seminar examined the ways that cultural context becomes part of art, with historic examples including how artists worked in the aftermath of the 1918 flu and World War I which led to vibrant movements like the Bauhaus, as well as artists such as David Wojnarowicz who created art that engaged with the politics and greed that ignored and fueled the devastation of the AIDS epidemic. The students were invited to respond to loosely structured prompts about creating art during this new era of upheaval.

“As we were all going through a pandemic and looking at what artists in the past had done, it felt like I was weaving myself into the fabric of a future narrative,” said Omar E. Saad, MFA Photography ’22. He explored using what he had on hand at home—such as the scans of negatives from previous photography projects—and spliced them into abstract collages. His final project centers on a sound project called “Beats in the Time of Global Pandemic” where he used lo-fi beats for tracks like “zoom based distance learning” and “time is fading” to represent the emotions behind his visual pieces.

Collage by Omar E. Saad, MFA Photography ’22, for “Beats in the Time of Global Pandemic”

“With the time the pandemic has given me, a chance arose to reflect on my past and present, how the two influence each other,” he said. “It has led to a body of work discussing my place within the Arab diaspora, through abstraction and sound. Also, not being able to go outside for a long period of time pushed me to further embrace my love of limitations. It gave me the ability to create more self-imposed boundaries to push my work further.”

Natalia Petkov, MFA Fine Arts (Sculpture) ’21, also found a new creative outlet in audio works in response to the class’s prompts. “I was trying to create an experience for the current audience, one that is experiencing art through our computers and devices,” she said. These experiments in sound made in her home were a change from her practice that had previously concentrated on sculptures that were created in a studio.

Natalia Petkov, MFA Fine Arts (Sculpture) ’21, “Untitled (frozen bird)” (2021), silver gelatin print, 16 x 20 inches

“My art practice has evolved so much over the past year,” she said. “The biggest shift has been embracing my creative process rather than fighting it. Prior to this time, I felt so much pressure to create art in my assigned studio, assigning time to be a maker, and forcing myself to work in the field of sculpture because that is what I have always done. During the pandemic, I began working in my kitchen and using walks and the outside world as an extension of my studio practice. I have continued to be inspired by the world around us and finding freedom to create work wherever I am in whatever medium or material is calling to me.” Her thesis exhibition, Shedding Our Skins, is a meditation on decay and how it can lead to new forms, with a floor filled with an installation of onion skins and photographs that capture the decomposition of objects she has found on her walks, such as the body of a dead bird.

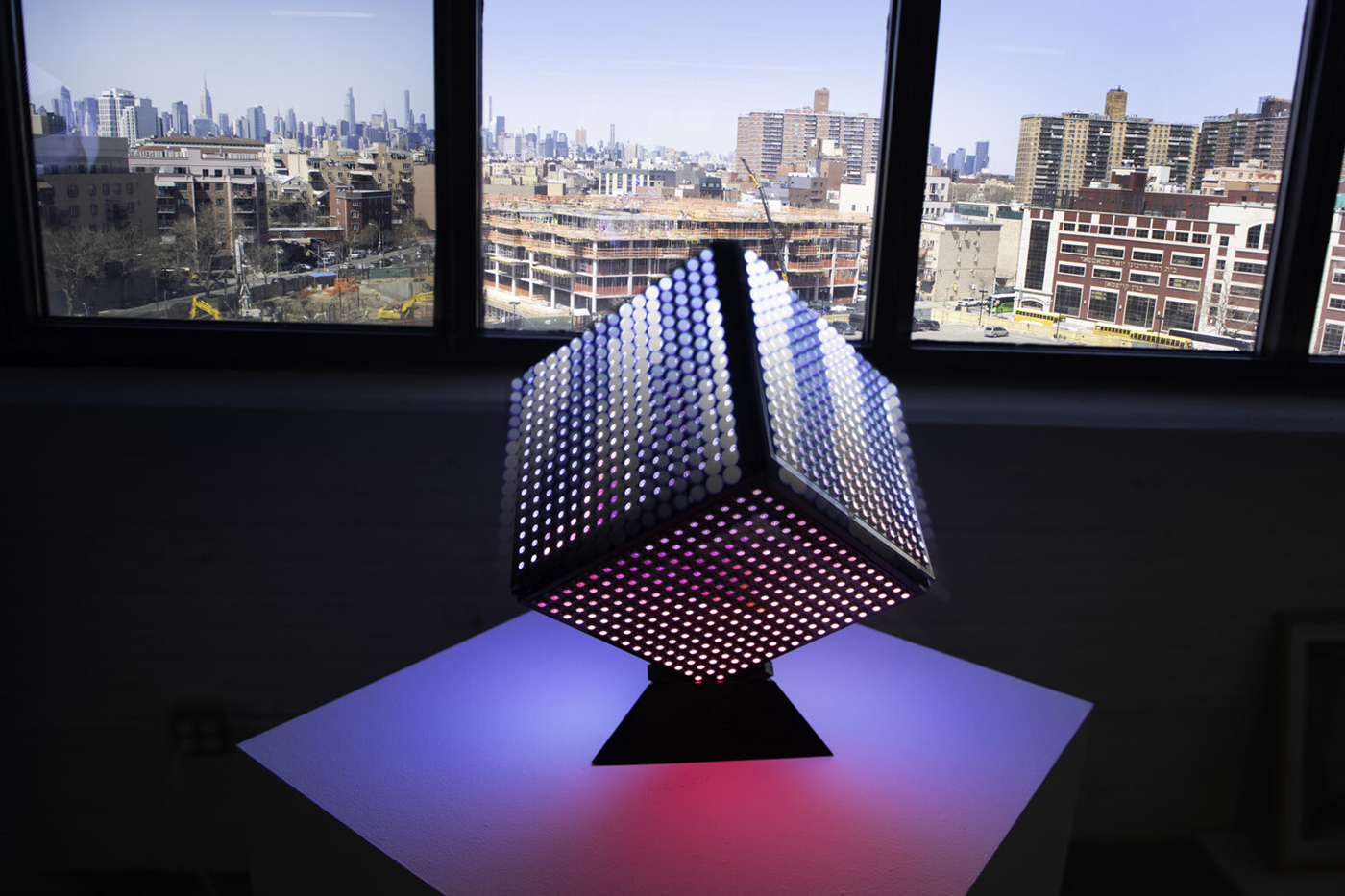

Joshua Boger, MFA Fine Arts (Printmaking) ’21, who was also part of the Art in the Time of a Global Pandemic seminar, similarly made a radical change in his practice over the past year. “I was primarily a printmaker, working with screen printing and different methods of conveying meaning through perspective and light,” he said. “The class really became about adaptation, seeing how we shift in response to the world.”

While Boger was in his apartment, with limited access to printmaking materials, he taught himself JavaScript and started writing code, eventually developing interactive games that reflected on his feelings, such a room that is impossible to escape. “Everything we could know was seen through our laptops,” he said. “I wanted to know how it all worked and changed how we understood what was happening.” He moved on to microprocessors and programming computers and simple robots, culminating with a mask that has a laser distance sensor with LED indicators that light up when someone is within six feet.

Joshua Boger, MFA Fine Arts (Printmaking) ’21, “Cambridge Analytica III”

His dataLine thesis show includes sculptural pieces involving these experiments with technology, such as LEDs and screens, responding to data structures in advertising algorithms and the marketing of politics. “In the time I spent learning these programming languages, the use of sensors, image collection, surveillance, and data gathering became central to my work,” Boger said. “The past year has impacted my work permanently, as it has for many artists. I think this shift in my work is parallel to the change I have seen around me. There really is no going back, only forward.”