For the Fall 2023 semester, Ashley Bales, adjunct assistant professor of math and science, wanted students in her “Anatomy of Motion” class to better understand the functionality of different parts of the body. Instead of turning to diagrams and dissections, she borrowed the design principle of simplification from discussions with Jonathan Scelsa, associate professor of undergraduate architecture. She asked her students to construct simple models of anatomical joints and to explore the materiality of the process.

Exploring materiality. Critical engagement. Finding relevance. These are some of the overarching Transdisciplinary Epistemic Practices (TEPs)—a theoretical framework that describes how transdisciplinary knowledge claims are justified—that a group of 11 Pratt faculty members from five schools explored over the past year as part of a National Science Foundation (NSF) project spearheaded by Chris Jensen, associate professor of math and science, Heather Lewis, professor of art and design education, and Mark Rosin, associate professor of math and science.

As part of the first phase of the “Transdisciplinary Approaches to STEM Teaching and Learning” project, the team refined, tested, and codified these practices to support the increasing number of educators who want to better help students integrate science and art ways of knowing, especially within the context of rapid technological advancement. Through guided and ongoing peer-led discussion and research in Faculty Learning Communities (FLCs), which included peer-observation in classrooms, the project participants collaborated on syllabi and assignment redesigns that introduced the TEPs, the results of which will inform the team’s application for phase two NSF funding.

“We’re interested in looking at what we can learn from each other as instructors in different disciplines and, then, how does that translate into the classroom?” said Jensen. “How do we help students transfer knowledge or skills they get from one class to others? Because if you get people to break down the walls between these disciplines, then you can get students to really think holistically.”

The faculty participating in this effort alongside Bales and Scelsa are Leanne Bowler, professor in the School of Information; Robert Brackett, adjunct associate professor of undergraduate architecture; Blake Marques Carrington, associate professor of digital arts; Rafael de Balanzo Joue, visiting assistant professor of math and science; Regina “Gina” Gregorio, adjunct associate professor of fashion design; Nurhaizatul “Zat” Jamil, assistant professor of social sciences and cultural studies; Jeanne Pfordresher, adjunct professor of industrial design; Sophia Sobers, adjunct instructor of digital arts; and Keena Suh, associate professor of interior design.

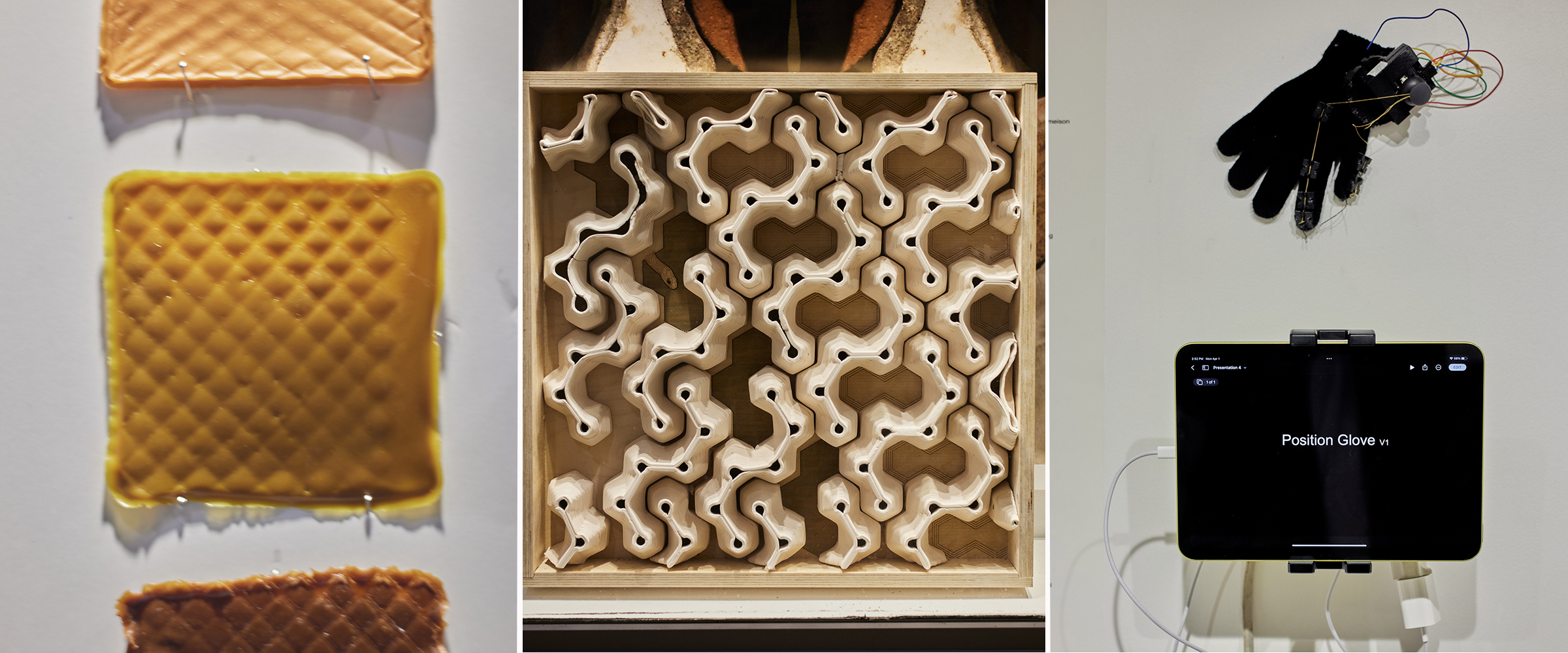

The outcomes from their research on their teaching were on display in the MSCI Gallery of the ARC in a multimedia exhibit that was curated by Borinquen Gallo, associate professor-CCE of art and design education, Lewis, and Suh.

“The exhibition was our way as an art and design school of making the research public and it’s quite unique in the field of scholarship of teaching and learning,” Lewis said. “In the show, every faculty member talked about which TEPs helped them think outside of their discipline or disciplinary practices and how these practices affected their ways of working. And what’s really fascinating about this project is the faculty did this as part of a community.”

Years in the Making

The theoretical basis of this project began with Rosin, who for years has been developing art installations and immersive experiences to share scientific ideas about climate change and sustainability at music festivals, public events, and corporate gatherings through his science education organization Guerilla Science. In 2017, Rosin was a key team member in an international research project funded by the NSF and the Wellcome Trust to think through what constitutes a successful pedagogical mix of art and science.

“There was this sense in the education and creative making communities that people knew what a really good project that integrates science and art looks like, they knew what good transdisciplinary practice was when they saw it, but there wasn’t a prescriptive guideline of things you could give to someone for their project to be transdisciplinary. Theory was lagging behind practice,” he said.

Rosin and his colleagues devised a tentative set of TEPs to give informal educators a framework for transdisciplinary teaching and learning. At the same time, faculty at Pratt were already teaching in a transdisciplinary manner based on new developments in their fields and disciplines, presenting an opportunity to experiment with and refine the TEPs.

“We were talking about the strategic plan and how integrative learning and transdisciplinary practice are very important for students, and how Pratt is perfectly positioned because we have this great architecture school, all of these maker facilities, digital arts, and lots of other areas where the arts and sciences come together,” Rosin said. “We wanted to come up with frameworks that are both guiding and giving license to educators to think more expansively in ways that actually reflect the nature of their evolving subjects.”

Rosin emphasized that transdisciplinary teaching can equip students with skills and perspectives they can use to navigate the future of work. The demand for this kind of learning has increased in the last few years. The most recent report from the Strategic National Alumni Arts Project documenting the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, found that 53% of recent art and design school graduates who responded to their survey want new skills to adapt to increasingly digital and multifaceted work contexts.

Building Towards the Future

During the Spring 2023 semester, faculty participating in the NSF project gathered on a monthly basis to discuss the TEPs and their relationship to different disciplines and approaches to teaching. They formed small groups for peer-observation sessions, where they would sit in on one another’s classes and share best practices. They also kept journals to track their progress within the project, presenting their findings to the larger group, and eventually worked in pairs to apply their insights and the TEPs to a specific course they taught in the Fall 2023 semester.

For de Balanzo Joue, this meant incorporating hands-on learning and community engagement components to his “Ecology in Architecture” course through work with Pratt’s geodesic dome. Sobers introduced iterative illustration assignments to her “Integrating Circuit Diagrams and Enclosures” to help students better see the digital controllers they were making as part of their larger art projects. Scelsa, meanwhile, borrowed insights about the variabilities of ecology from his discussions with Bales and encouraged students in his “Riprap Ram Jam” studio architecture course to let their ecological restoration proposals unfold in response to local environmental conditions.

The overall findings from these and other efforts will now be synthesized by Jensen, Lewis, and Rosin to apply for phase two funding to expand the project’s scope and impact, with the eventual goal of bringing the TEP framework to broader audiences both within and beyond Pratt.

“The next stage would be to see if we could really have this work affect students more directly on scale,” Rosin said. “We’d really like people who operate at the curriculum or program level to incorporate this structurally into the work they’re overseeing. We’d love it if a degree program wanted to start using some of this work to help guide the creation of new syllabi, or do professional development that can help faculty grow as teachers and curriculum designers, recognizing that there’s value in being a bit more systematic about how we support our students and faculty to engage with these new subjects.”