Before synthetic color emerged in the 19th century, all dyes came from natural sources. A project led this fall by Ana Codorean, MA Art and Design Education ’22, connected elementary school students in Brooklyn to this now often overlooked connection between color and nature. Using the Textile Dye Garden that was planted on the Pratt Institute Brooklyn campus in 2021, the fourth graders and their teachers, along with members of the Pratt community, examined the relationships between the environment, its pollinators, its diverse plants, the science of color, and the vibrancy of art and textiles.

“Demystifying textiles was an important part of this project because it’s so mysterious how fabric is made,” Codorean said. “I wanted to find a way to do a curriculum that teaches students how to use natural dyes. I love how holistic the process of working with natural dyes is; you grow these plants, turn them into dye, use that to dye yarn, and you can weave it. You can be involved in every part of the process.”

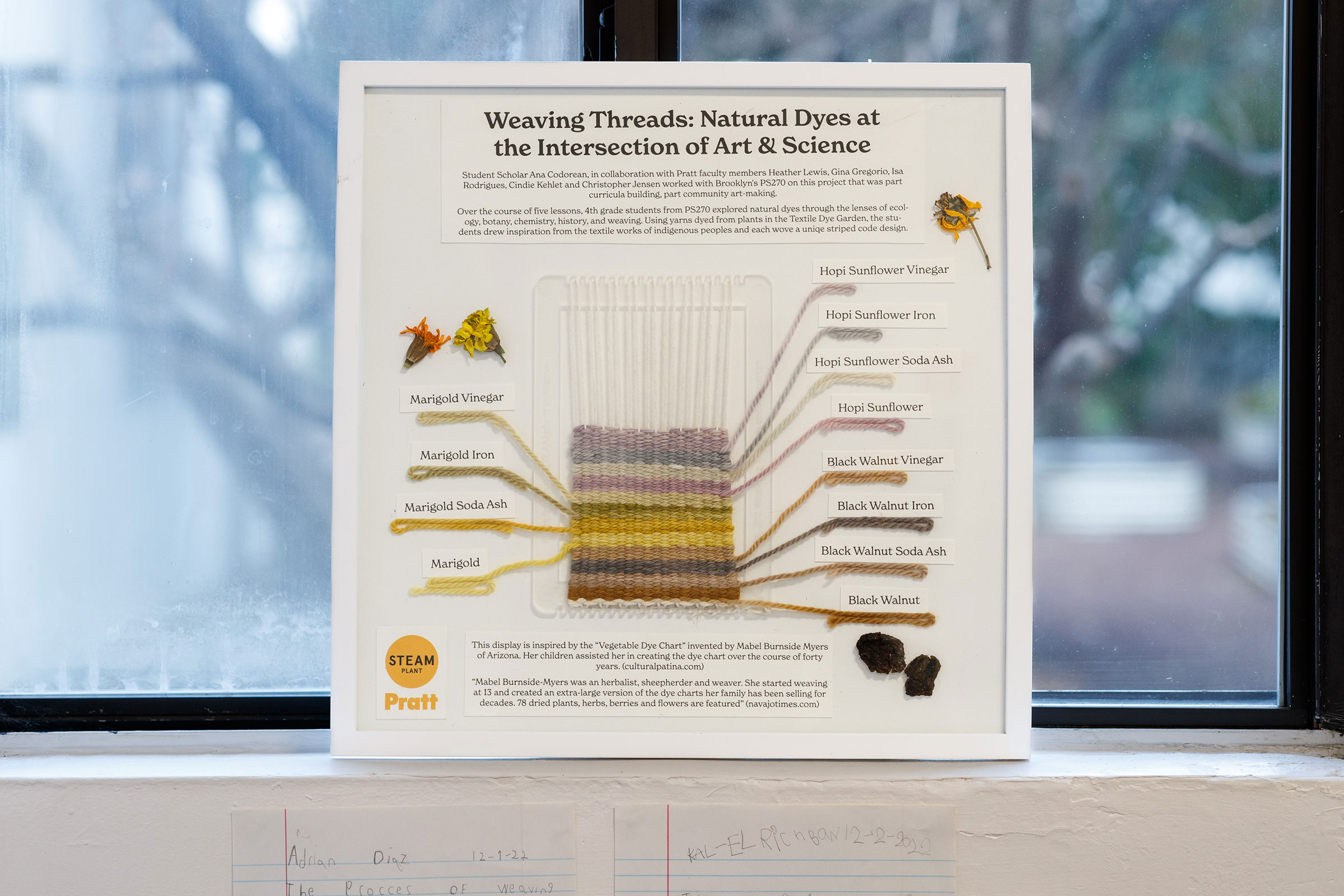

Called “Weaving Threads: Natural Dyes at the Intersection of Art & Science,” the interdisciplinary teaching project was led by Codorean in collaboration with Pratt faculty and teachers and administrators from public school PS270. Codorean received a Sirovich Family Student Scholarship through Pratt’s STEAMplant Initiative which facilitates interdisciplinary projects engaged with the ideas of STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, the Arts/Design, and Mathematics) as well as broader creative disciplines. Daniel Wright, the director of STEAMplant, stated that the project reflected the initiative’s goal of bringing together people in different departments through an “engagement with science,” adding that “we’ve had other projects that had students involved, but this one focused on the graduate student really running the show.”

PS270, which is located alongside the Brooklyn campus, already had a relationship with Pratt’s Center for Art, Design, and Community Engagement K-12. “You can literally see the school from the Textile Dye Garden,” Codorean said. “Elementary schools are really open to these kinds of project-based learning and we could work closely with their classroom teachers.”

“Weaving Threads” involved an interdisciplinary group of faculty in developing teaching materials and leading the sessions at PS270 and in the Textile Dye Garden, including Gina Gregorio, adjunct associate professor of fashion design; Christopher Jensen, associate professor of math and science; Cindie Kehlet, acting chair of math and science; Heather Lewis, professor of art and design education; and Isa Santos Rodrigues, visiting assistant professor of fashion design.

“My focus was on getting the students to think about the interdependence in ecological systems, so they could understand why the plants have this lifecycle, what is the role of pollinators, and why you would want to plant a garden to help the pollinators,” Jensen said. “A big part of it was thinking about ways to bring different disciplines together in a common language.”

This included working with Codorean on class materials such as posters and a video that introduced the students to the garden before they arrived on campus. Once there, they had the opportunity to closely examine the flowers, from goldenrod to yarrow, with magnifying glasses and sketch their observations before experimenting with bundle dyeing using flower petals.

Each of the sessions highlighted several related concepts, such as the responsible harvesting of flowers that respects the needs of pollinators and the benefits of natural dyes to people and the planet compared to the toxic ecological impacts of synthetic dyes. In the PS270 classroom, they explored how several color variations of dye concentrate could be made from just three plants—marigold, black walnut, and Hopi sunflower—by understanding the pH scale, whether using vinegar to lower the pH levels or soda ash to increase them. The marigolds and Hopi sunflowers were harvested from the garden, while the black walnuts were locally foraged.

The experience deepened the students’ learning in a school unit of study on Indigenous people of New York, as they were able to see how the dyes they made corresponded to the colors on objects and art created by the Lenape, Oneida, Canarsee, Mohawk, Seneca, Onondaga, and Haudenosaunee people.

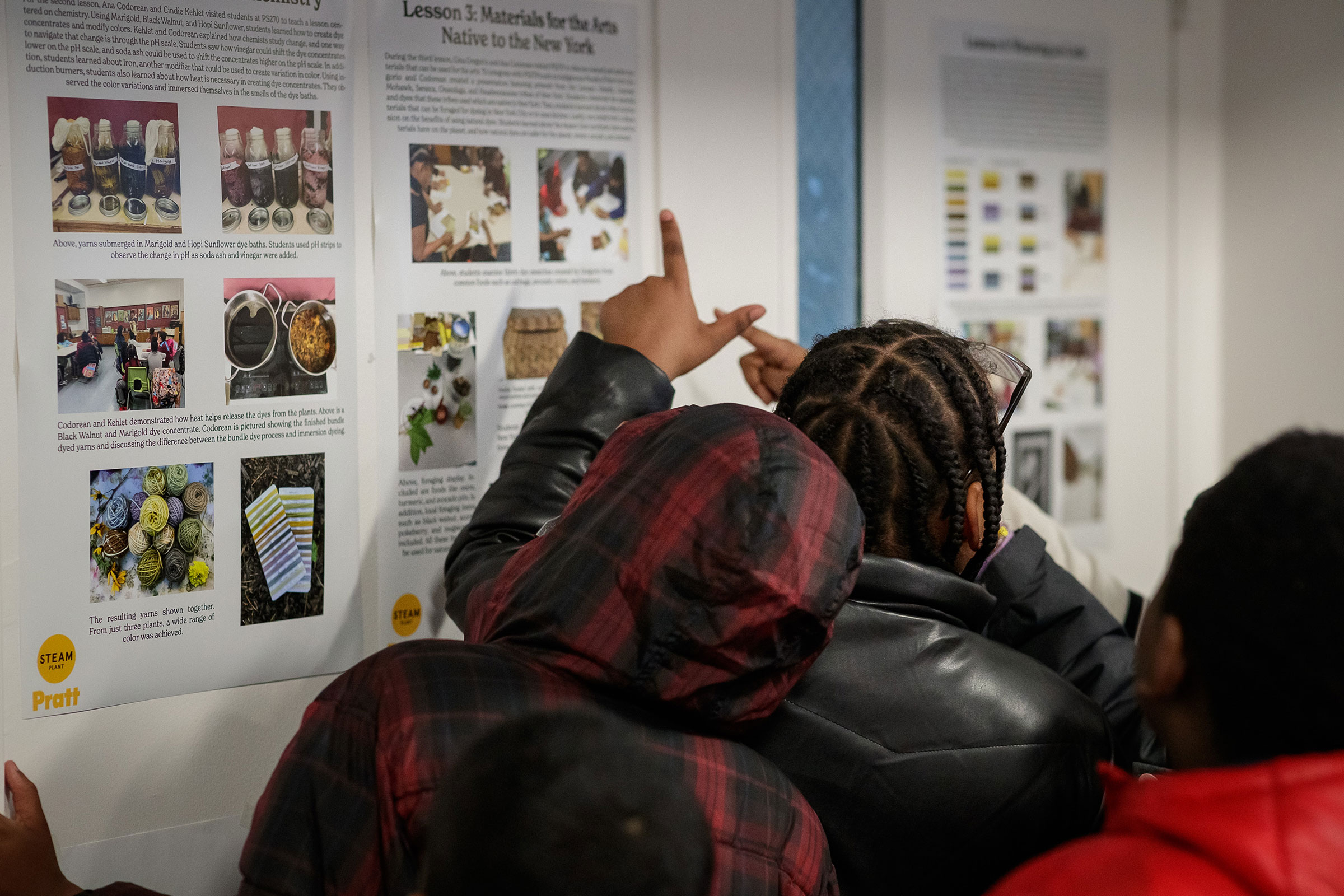

The students also explored the relationship between weaving and code, such as the jacquard loom which was the first iteration of a computer and binary coding, and also learned how symbolism through stripes or motifs can serve as “codes” of communication. They then used yarn they had dyed to create their own weavings and were encouraged to embed them with patterns and symbols to tell their own stories.

“This project was also a learning opportunity for the faculty in translating an understanding of chemistry so it can be understood by this age group of kids,” Lewis said. “There are so many layers in this project, which involves learning art skills like weaving, science, and the historical connection to Native American culture. It was a really collaborative curriculum that unfolded with Ana leading it.”

At a culminating event in the Textile Dye Garden on December 12, the students exhibited their weavings alongside classroom materials, such as examinations of how weaving heritage connects to technology and visualizations of how each person is within a community that extends to the surrounding nature. They joined in helping to plant seeds in the garden beds so that come spring, they will get to see the hand that they have in the flourishing of this interconnected world.