In September 2020, Linda Lauro-Lazin, assistant chair of digital arts, released 28 lanterns that floated down the Wallkill River in Rifton, New York. The number represented the weeks that New York State had been on pause, each lantern carrying with it words from an individual about their experience, some coming from around the world. Called Floating Grace, it was a way to mark time and loss in a way that brought people together even as distancing remained important.

‘Floating Grace’ by Linda Lauro-Lazin, assistant chair of digital arts (photo by Jaykumar Patel)

Lauro-Lazin continued to transcribe one message on a new lantern each week. “Every night—weather permitting—I lit lanterns on the shoreline of the Swartekill Creek, below my studio and visible from the road,” she stated. A year since that initial launch and the pandemic is still ongoing and its toll of people lost, time fractured, and lives upended demands a new kind of memorialization. She is now planning another release for the fall. “I think of this as an offering—sending the words and light out into the world via the waterways.”

Like Lauro-Lazin, several Pratt students have been examining these ideas in their work to investigate how art and design could create spaces for grief, reflection, community, and moving forward.

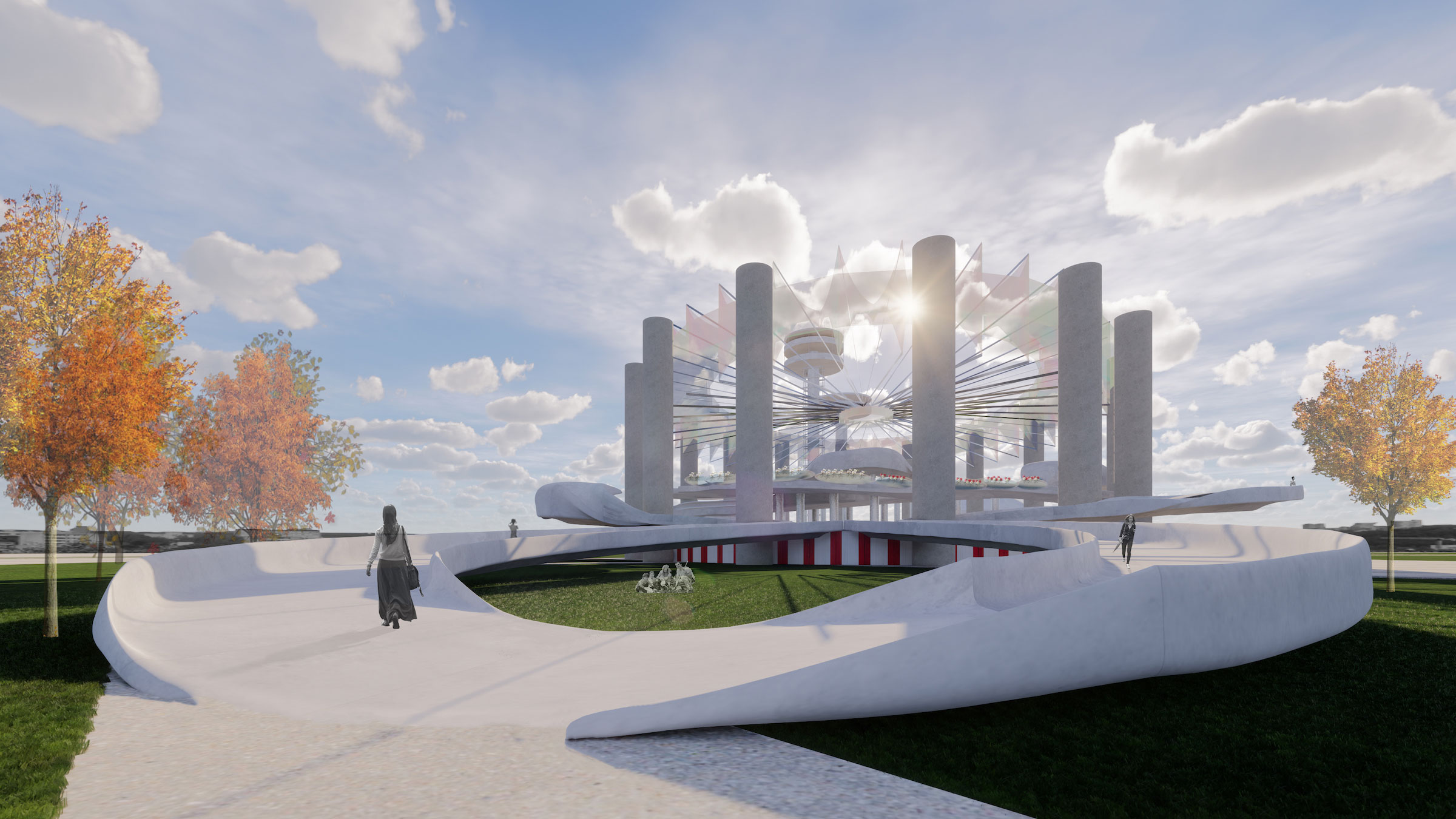

“Living Cycle: Mourning and Healing as a Part of Life” by Shirley Chen, BFA Interior Design ’21

In her thesis studio, Shirley Chen, BFA Interior Design ’21, created “Living Cycle: Mourning and Healing as a Part of Life” which reimagined the New York State Pavilion in Flushing Meadows–Corona Park, Queens. A healing path would transport visitors into interconnected spaces for celebrating, making, mourning, and other experiences, all circling interior plantings of flowers. “Through my research, I learned that death in Western culture has often been something that should be hidden or invisible,” Chen said. “In contrast, other cultures embrace death as part of life and celebrate it as a transition to a new beginning.”

She explained that she chose the Pavilion—a 1964 World’s Fair site that is currently empty—due to its proximity to the diverse communities of Queens as well as several cemeteries. The circular shape of the structure designed by architect Philip Johnson lends itself to recognizing life and death as a continuous cycle with the floral plantings beautifying the abandoned site, making it a place people would want to go and share in a journey while having the space to engage in their own rituals.

With the upheavals of the pandemic, Chen noted that it was especially vital to find ways to heal and remember the departed together. “Sharing these memories is a reminder to value what we have and live your life to the fullest as we never know what is next,” she said.

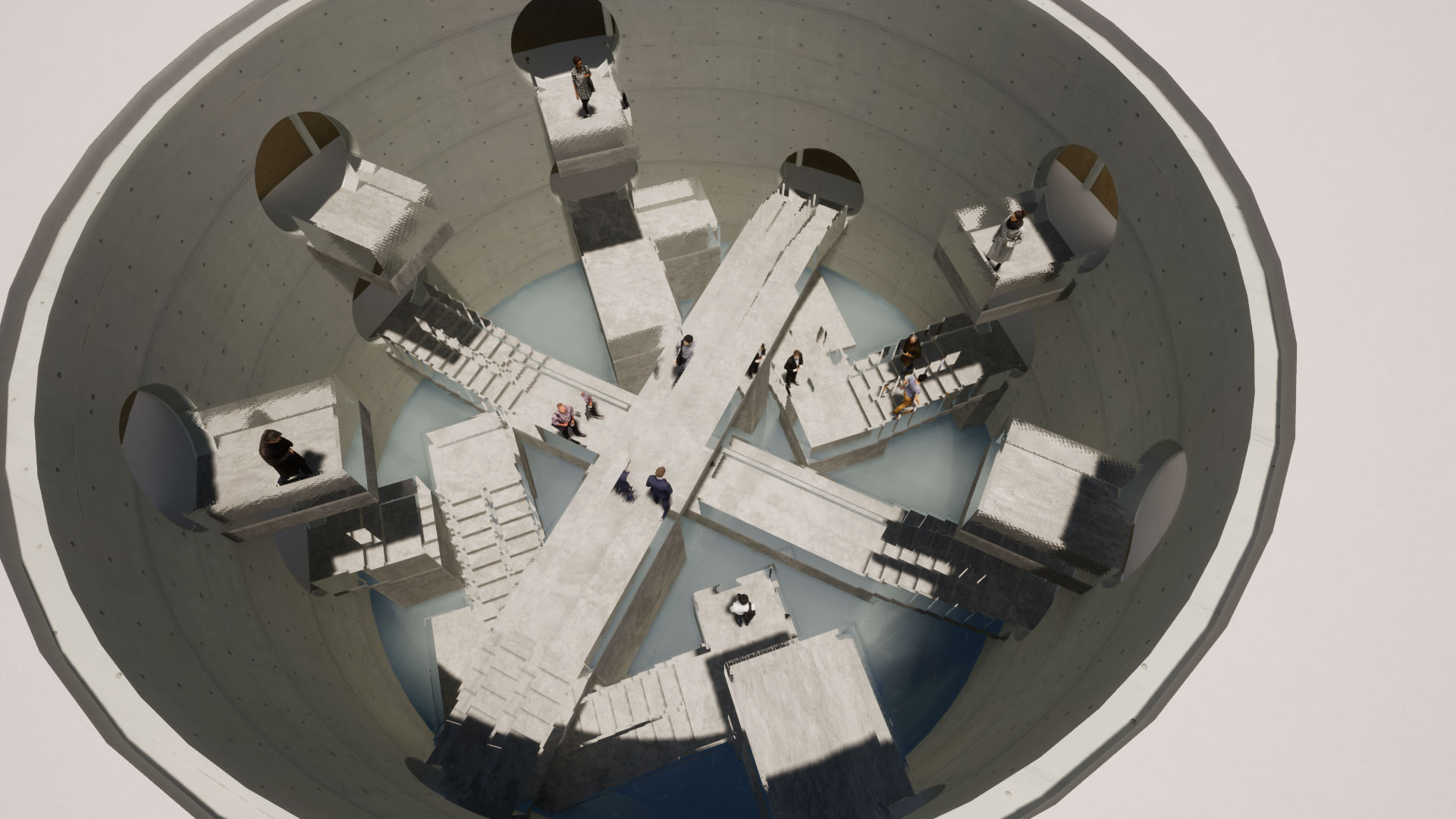

“Re-Encounter” by Xuan Zhang, MFA Interior Design ’20

Xuan Zhang, MFA Interior Design ’20, likewise designed a space where the living could gather while remembering the deceased. “I think one of the best ways to memorialize COVID-19 is to use space to let people remember their behavior and feelings during the epidemic,” Zhang said. “Such as getting lost, quarantined, and regaining hope.”

His “Re-Encounter” project was a top design in the recent COVID-19 Memorial Design Competition hosted by DesignClass. It engages with how public space and the way people experience it have been changed by the pandemic. A central circular memorial hall is embedded with a negative space that “represents this missing part, and the visitors walk into the hollow in the center to mourn.”

The act of memorializing would come through the movements of visitors, such as passing through 14 portals to the center hall, each accessed from a different level, each remembering a person who died on the frontlines of COVID-19. Transparent materials throughout the interior would further, as Zhang explains, suggest “the feeling that people can see but cannot touch each other during the epidemic.”

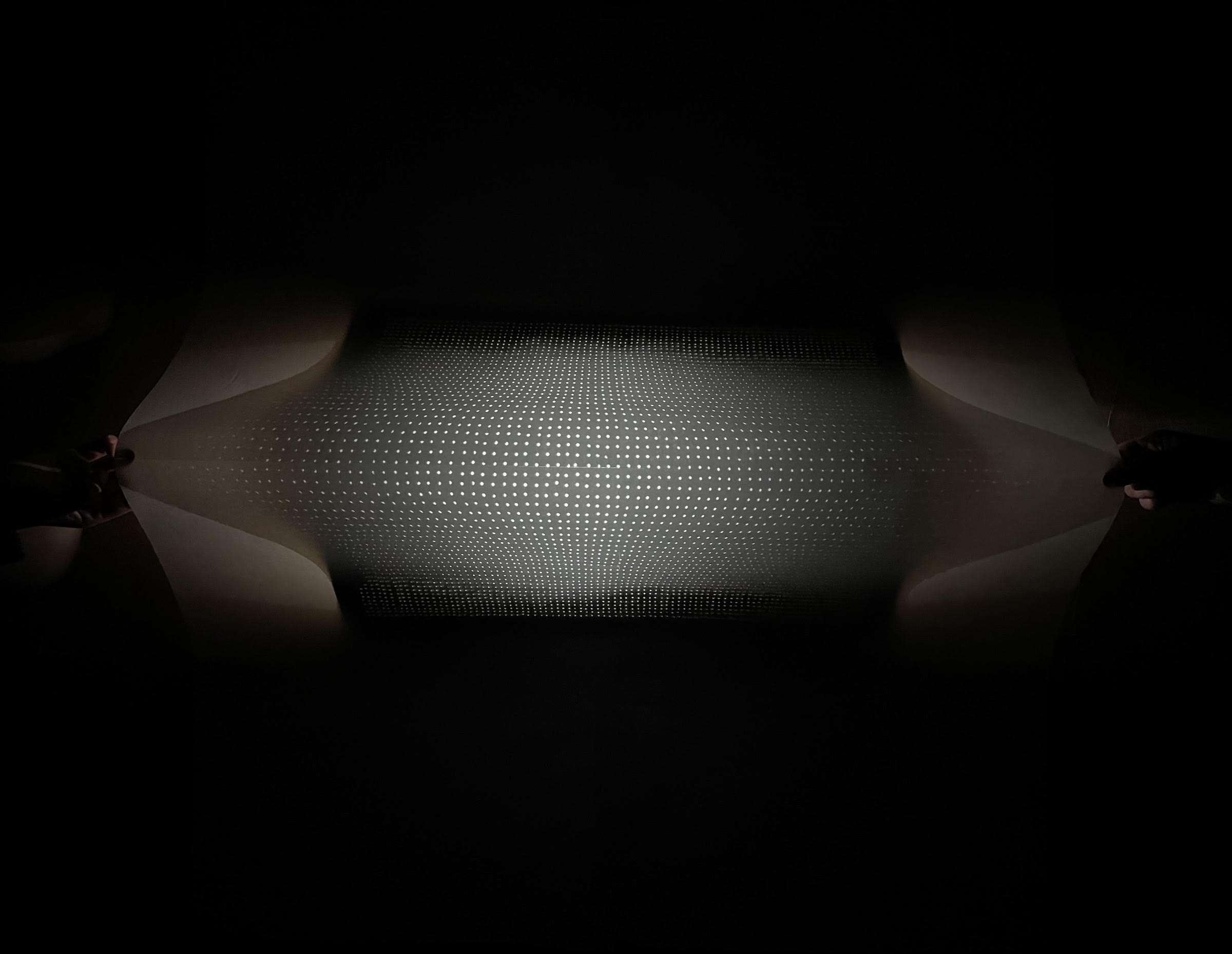

“February 4, 2021” by Rose Moon, BID ’23

Rose Moon, BID ’23, was considering how to express the pandemic’s soaring scale of death and grief in developing “February 4, 2021” for a design studio led by Willy Schwenzfeier, visiting assistant professor of industrial design. It recently received second prize in IESNYC’s Student Lighting Competition.

Referencing a day when the mortality rate in the United States reached an unprecedented height, her work involved punching 5,117 holes—one for each death—into a large metal sheet. The meditative process visualized each of these lives, with a light projecting through the openings onto a paper veil illuminating the impact of a single day.

“By scaling down and compiling each of these lives into pinpricks of light, I was able to better comprehend the amount of lives lost as well as grief caused through visual reference,” Moon said. “Unlike CDC charts, my piece attempts to connect viewers to our current situation in a more emotional manner rather than purely factual.”

For Moon, it was crucial for viewers to relate to people they likely knew only as a number, something she hopes to see in future remembrances of the pandemic. “In order to memorialize COVID-19, I would love to see more pieces that help us comprehend the weight of this event visually through scale manipulation,” she said.

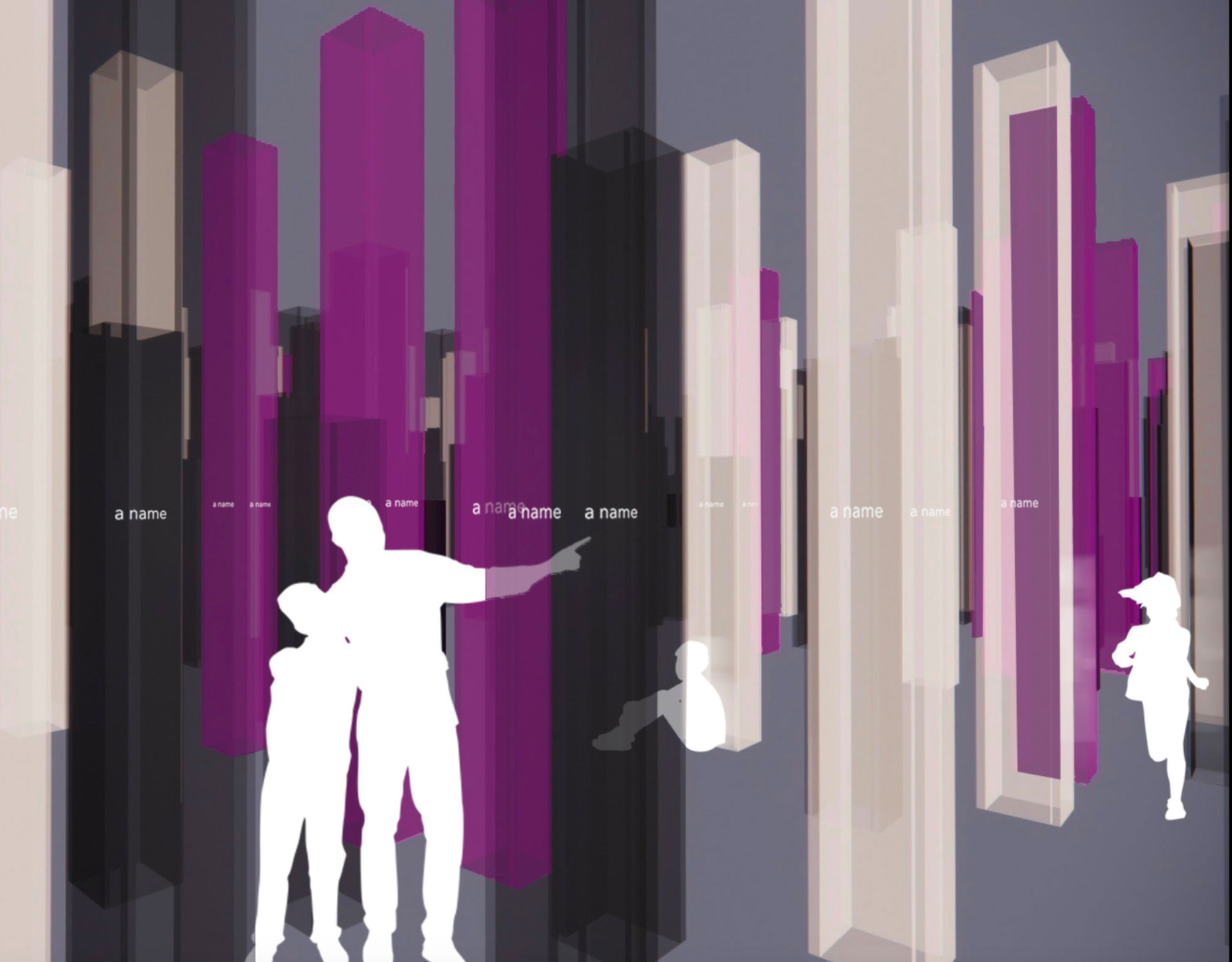

“In Memoriam of Lives Lost to Covid-19” by Kats Tamanaha, MFA Interior Design ’21; MS Sustainable Environmental Systems ’21

Kats Tamanaha, MFA Interior Design ’21; MS Sustainable Environmental Systems ’21, was also exploring different scales of memorialization in her “In Memoriam of Lives Lost to Covid-19” completed for a summer interior design studio led by Sheryl Kasak, adjunct professor-CCE of interior design. “My ideas behind the project were to create a space where its meaning would change over time and depending on the user,” Tamanaha said.

Her memorial is an immersive virtual world of cenotaphs that visitors can navigate, allowing for both personal and collective experiences. The cenotaphs—tall monolithic structures—would represent single deaths, the height of the pillar determined by their age, with their placement relating to where they lived geographical, so viewers would instantly understand personal information about each individual. Their interiors would offer private experiences where people could remember a specific person, with imagery of a sky able to be manipulated to speed up or slow down as a meditation on time.

“I think our memorialization of COVID-19 needs to take into account these overlapping dynamics of immense personal loss, collective trauma, vulnerability, globalization, and technology,” Tamanaha said.

“Remote Mourning & Online Funeral” by Naixin Kang, MID ’21

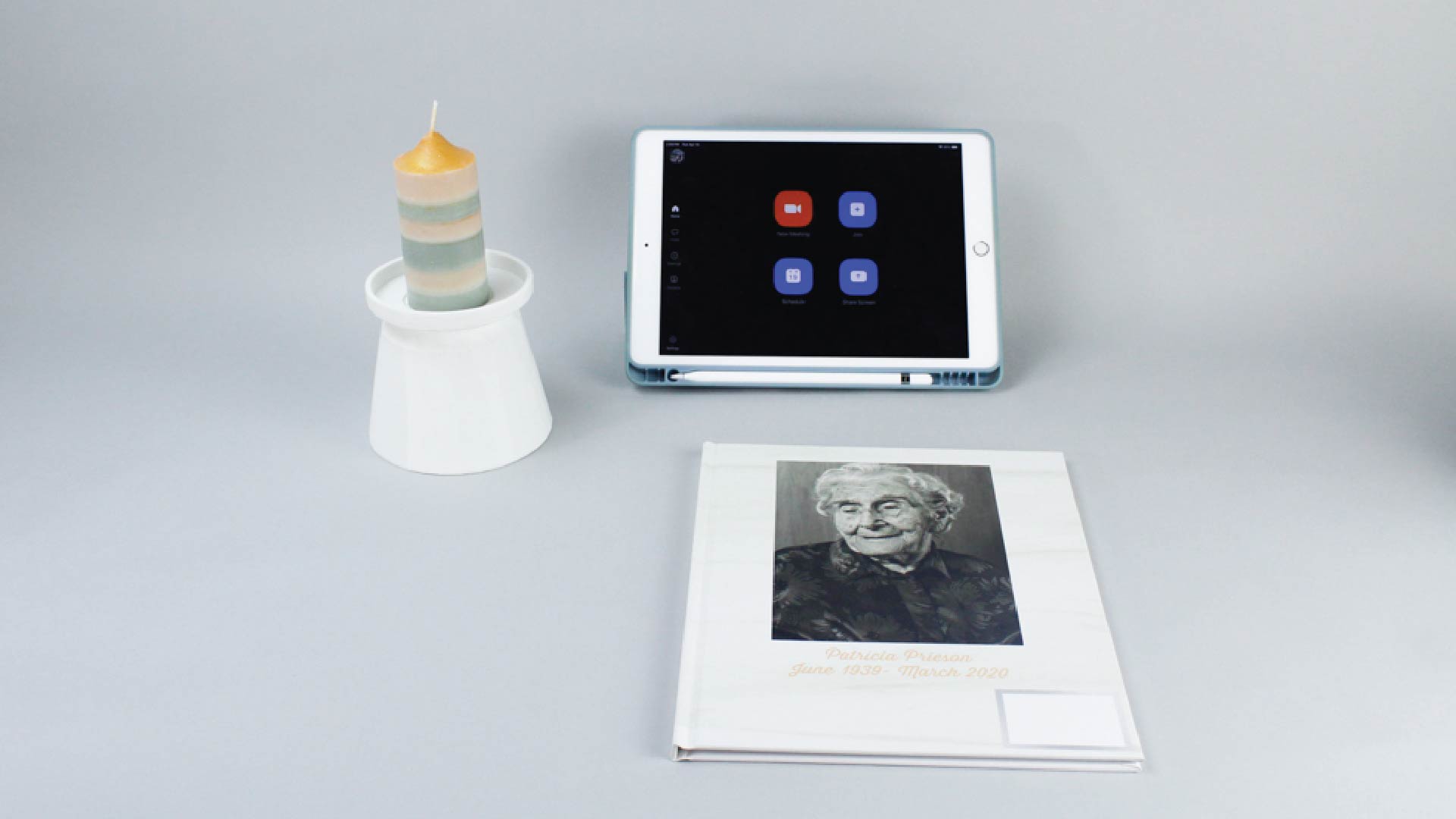

For her thesis project, Naixin Kang, MID ’21, was similarly looking at how technology could have a role in new forms of memorial. She noticed how there was an increased need for Zoom funerals and online memorials and developed an online funerary system that could be tailored to different needs. It would be complemented by tactile objects, such as candles and photo albums. The candle holder is designed with a small box inside that holds a link to a digital site for leaving condolences and memories.

While online funerals have been especially important during the pandemic when lockdowns and distancing have kept people apart, Kang sees their long-term potential in bringing people across the world together.

“The topic was inspired by the current situation, but as an industrial designer I always want to explore new fields,” Kang said. “The funeral is one of those human activities that has been influenced by the current situation. It’s about emotion and expression, an experience so many people need.”

Pandemics have rarely been memorialized in public ways, whether in monuments or commemorative public spaces. Often this kind of healing takes place in private. Whether a flotilla of lanterns on a New York river or a memorial held over Zoom, these projects bring that loss into the community where gathering and mourning become powerful acts of moving into a brighter future without forgetting who was left behind.