Master of Landscape Architecture (MLA) students were collecting soil samples in different parts of Brooklyn’s Gerritsen Beach this past winter when they came across “a large elm tree that didn’t exist anywhere else in the entire space,” according to Connor Jacobs, MLA ’26.

It was an unexpected discovery that neatly conveyed how humans alter landscapes in unintended and enduring ways, with the elm likely emerging from a seed dispersed in a dump years ago, he learned.

This kind of land-based learning is a distinct part of the new professional three-year MLA program in the School of Architecture, offering students the opportunity to gain first-hand experience that they can bring into the design studio.

Throughout the first year of this annual core course, the students investigate various soils around Brooklyn and New York, considering the environmental impact of urban life, while learning core principles and techniques of landscape architecture as part of the “Cartography II: Soil Making” class taught by Visiting Professor William (Bill) Bryant Logan and Visiting Assistant Professor Melody Stein in the Graduate Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and Urban Design department.

“We teach students to recognize that soil is a living being with millions of organisms in it,” Logan said. “As they become better designers, they’ll need to know how to work with soils and plants, how to visually represent these things, and how to talk intelligently about the changes they want to make to the land.”

“This idea of deep sensing of the land is really critical to the course and a precursor of design,” Stein said. “The second semester students begin to understand how environments became the way they are so they can begin to imagine how these places will evolve. The land is already on a trajectory; constructing a project impacts this trajectory and sets a new course.”

The two professors blended their different backgrounds for the course, with Logan overseeing lessons on soil biology and plant life and Stein leading on concepts, tools, and technologies related to landscape architecture. The dual focus reflects the overall structure of the MLA program, developed by Academic Director Rosetta S. Elkin, which encourages students to acknowledge the relationship between living environments and built communities, while also equipping them with the professional skills needed for their careers, and towards professional licensure.

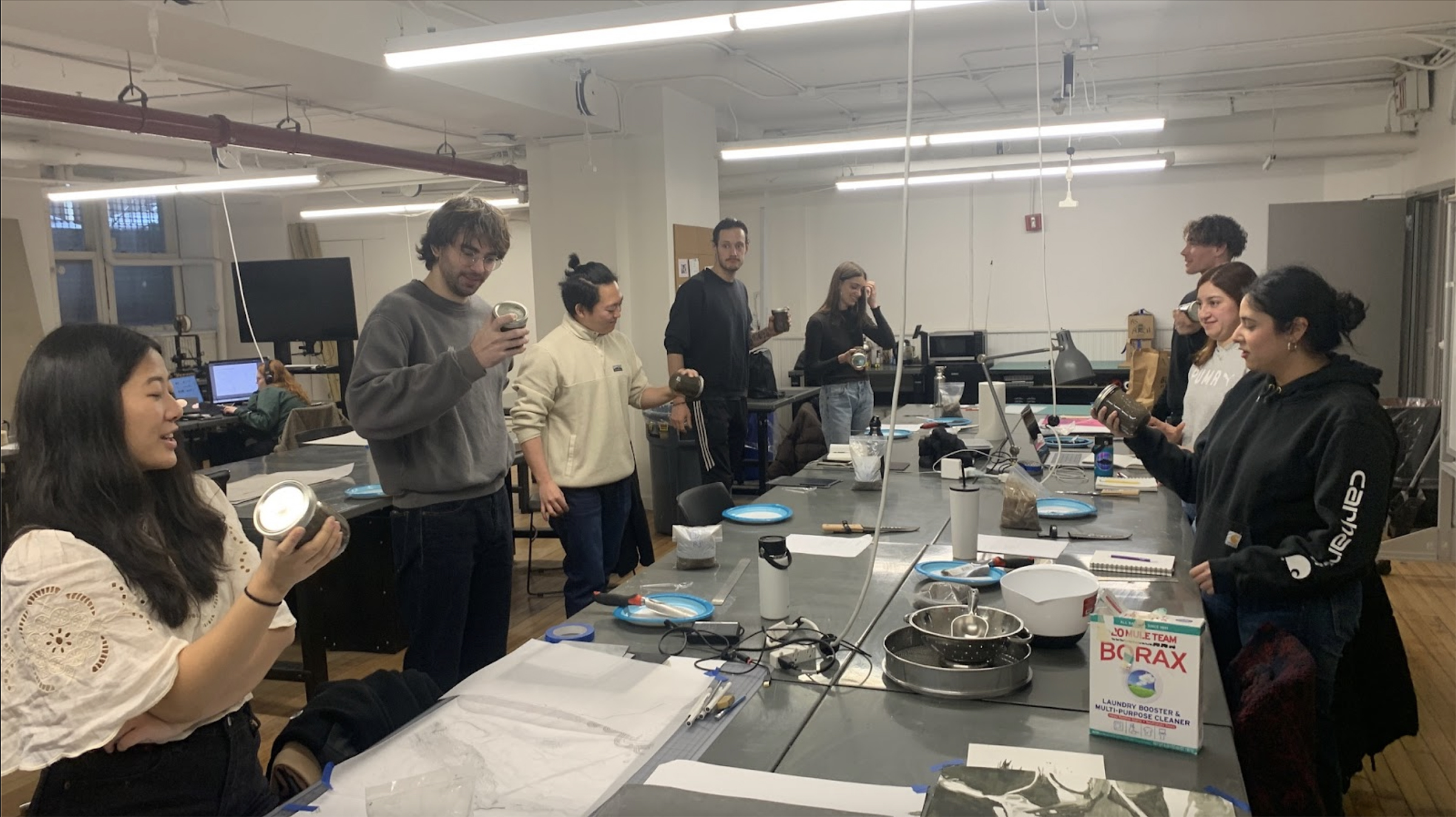

The annual Gerritsen Beach field trips take place early on in the semester as students proceed to visit other sites, including the High Line, Battery Park, and areas surrounding the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where they often meet with landscape architects and professionals in adjacent fields. At each site, students collect soil samples that they learn to analyze using a simple test measuring carbon dioxide levels, which indicates organic activity within, as well as tests to examine soil texture and pH. Students also review the five factors that shape a soil’s biography: “mineral parent material,” age, climate, biological organisms, and slope.

“I had some knowledge about soil based on things like composting here in New York City because I’m pretty active in my community garden,” said Tim Nottage, MLA ’26. “But I didn’t really know anything about the nuts and bolts of soil formation. So it was good to be learning about these principles over time and just getting a picture of some of the different tools and considerations as designers that we need to be thinking about like critical root zones and the relationship between soil and plants.”

“Bill talked us through all of the different aspects of soil and Melody has a grading background so we were getting both skills at the same time and learning how grading the land is impacted by soil ecology,” Chloe Kellner, MLA ’26, said.

Grading is a technical skill for shaping land. It takes into consideration variables like the slope of the ground, the vertical change desired, and the horizontal distance of a project when transforming land. The class studied the basics of drawing and grading the land, practicing manual grading on paper, moving on to the design program AutoCAD, and eventually worked with a computer numerical control (CNC) milling machine on Pratt’s Brooklyn campus.

“It’s a really valuable tool for modeling different landscapes and topography,” Jacobs said. “Part of what we’re being taught to do is think and design through the process of making rather than just thinking with a notepad. We’re encouraged to make models as part of the initial process, not just to replicate the finished project.”

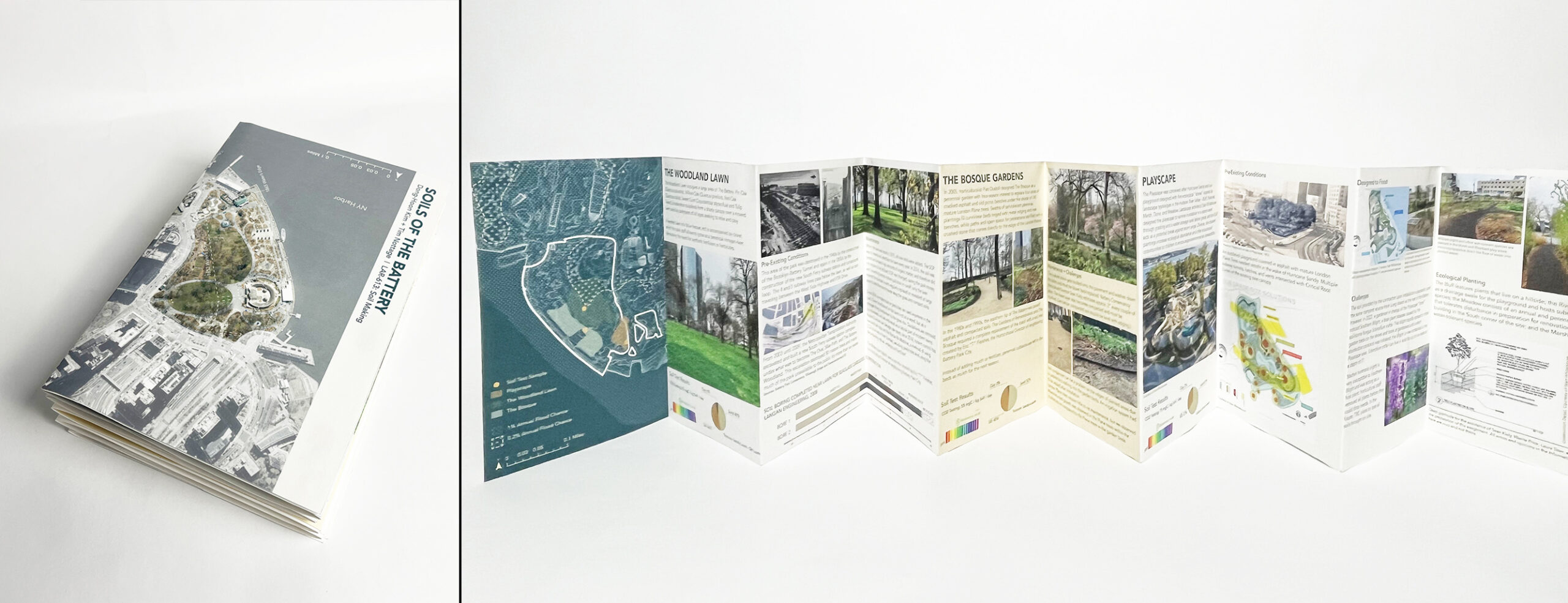

Research projects allow students to practice the skills they learn. Jacobs, Kellner, and Nottage analyzed the soil conditions of Gerritsen Beach, learning to visualize changes to protect and transform different aspects of the landscape through a design vision that anticipates changes in the urban ecology.

These efforts prepare students for the successful development of their studio projects in “Land Studio II: Shore,” taught by Assistant Professor of Landscape Architecture Mariel Collard.

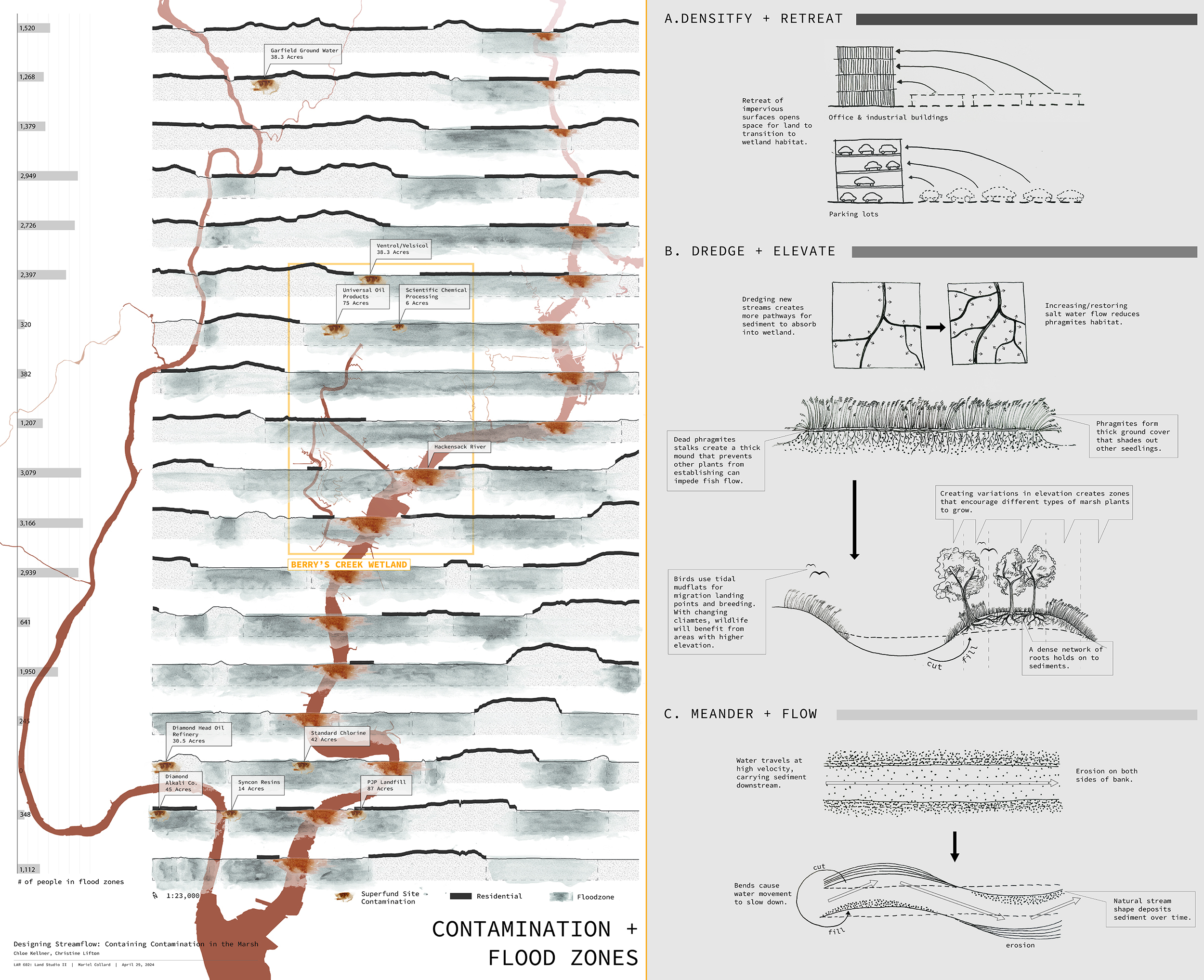

“This course considers retreat and rewilding as critical design concepts and climate adaptation strategies for the New Jersey Meadowlands,” said Collard. “The students study the interactions between the land and the sea to understand the shore as a thick, living, and dynamic gradient. They investigate the histories of this particular landscape through evolutionary time, to understand its current pressures, wildlife patterns, local and federal policies, environmental vulnerabilities such as sea level rise, and the legacies of aggregate human impact.”

Recognizing this history, students propose projects for living shorelines in landscapes affected by pollution, industrial activity, dumping, and land reclamation for development in marshlands. In the process, they work on 2D and 3D landscape representation models iterating between analog and digital techniques, while developing a better understanding of hydrology, ecology, and climate adaptation concepts.

This second semester design studio partners with Terry Doss, chief restoration scientist at the Meadowlands Research and Restoration Institute, allowing students to work directly in-the-field to complement their in-studio work. In situ analysis of landscape conditions teaches students to work in real-time, gathering data and learning about how the area’s wetlands evolved over time.

“The four projects developed through the studio imagine how the actions of unbuilding, removal, subtraction, or retreat can give way to resilient and biodiverse landscapes,” Collard said. “The students’ final work included a model for remediation that expand the EPA’s Superfund Program, a proposal to raise critical infrastructure that allows for tidal action to return to the marshes, the expansion of a remnant forest, and a watershed-scale plan to amplify water flow and sediments capture.”

“The analog work that Mariel proposed and the way that the structure of the assignments in the class are organized is particularly ingenious for building critical skills, and thinking through drawing and making in particular,” Nottage said. “I think it’s a really valuable education.”

The mixing of core skills and concepts are unique to the MLA program, a cumulative method of study designed by Elkin that encourages students to think through pressing issues such as the climate crisis and biodiversity loss as they learn how to draw landscapes, work with technologies, and create a more resilient public realm.