As New York City rebuilds in the aftermath of a long pandemic year, Pratt students are partnering in the local Brooklyn community and beyond to support a better, more equitable future with innovative solutions. In the Making a Difference series, Pratt’s news page is highlighting ways in which students and faculty have been working towards positive change in areas including sustainability, climate change, social justice, civic engagement, and public health. This article is the third in the series.

While many planning programs have a large project where students work with a community-based client as the culmination of their studies, Pratt Institute’s Graduate Center for Planning and the Environment (GCPE) in the School of Architecture offers it as a first-semester class so students immediately begin understanding how their work can impact communities. When planners work in partnership with a community-based organization, students can better understand the issues involved, as well as the concerns and priorities of residents. This local agency in the physical and economic development of the neighborhood is especially essential in underserved urban areas.

Each academic year, incoming City and Regional Planning students work with a different local community group. Many of these groups are recurring, with GCPE establishing long-term partnerships across the city. Recently, the students in the Fundamentals of Planning Studio led by GCPE faculty members Ayse Yonder, Juan Camilo Osorio, and Mercedes Narciso worked with the Brownsville Community Justice Center (BCJC). A project of the Center for Court Innovation, BCJC is dedicated to creating a safer and healthier neighborhood and a more effective, fair, and humane justice system in Brownsville in eastern Brooklyn. Having seen an earlier studio project from GCPE in Brownsville conducted in 2015, BCJC invited Pratt to work in Brownsville again, this time with a concentration on economic development along Belmont Avenue with a focus on youth in the area.

“Because it’s a first-semester studio, they have to look at all the topics that involve planning,” Narciso said. “They have to study the neighborhood from all angles: community development, housing, land use and zoning, historic preservation, climate justice, environmental justice, and other topics to do an assessment of the neighborhood.”

Spending time on the ground in Brownsville, meeting its residents—such as in digital community visioning sessions focused on young residents—and walking its streets, and collaborating virtually as they adapted to the pandemic, the students created a report on “Planning for Community Economic Development and Solidarity in Brownsville.”

“It’s a steep learning curve,” Yonder said of the students’ experience. The studio process engages the students in all the skills they will need as planners, from researching the existing conditions of the neighborhood to proposing objectives for improvement. The students build on this research in order to frame planning recommendations for the client’s consideration for implementation.

“This class really drops you into planning in a real way and pushes you to learn and problem solve on the spot,” said Leanna Molnar, MS City and Regional Planning ’22. “Working with a client and with a team of students emulates real-world planning by sort of outlining how a longer-term planning process might go. The class also teaches how to incorporate community input and your client’s needs into an idea and a planning report, which is as close to real planning as you are going to get in a classroom setting.”

For the BCJC report, the students’ investigation included methods for promoting community autonomy through wealth-building initiatives and local employment, using available space to encourage community connectivity, and enhancing this connection through participatory programming. The students broke into three teams that looked at the social, physical, and natural environment of Brownsville and then presented their findings to BCJC as a group around the middle of the term. The second half of the semester was devoted to planning recommendations that would create opportunities for economic development to improve the livelihoods of youth in the community, including access to economic development, public health, and open space and recreation.

“We work with communities so the students know who the boss is,” Yonder said. “They learn the technical skills of planning, but the most critical thing is they learn to work as a team and how to respect each other and adapt to different processes of working. Everyone has to contribute and they have to listen to each other.”

Healing Sanctuaries at Osborn Plaza in Brownsville (courtesy A+A+A)

Brownsville has the country’s highest concentration of public housing and one of the highest levels of incarceration. In examining the neighborhood’s history, the students learned about the impacts of systemic disinvestment. This included wellness and mental health services—which have been a significant challenge during COVID-19—but they also learned about an outstanding sense of pride and resilience from local residents, particularly young adults, who are working to address neighborhood disparities by envisioning a more just and equitable future for their neighborhood.

Among the students’ proposals for place-based initiatives was an idea for expanding BCJC’s Healing Sanctuaries program. The project previously involved the A+A+A design studio co-founded by Ashely Kuo, BFA Interior Design ’14, which helped install mobile spaces in Osborn Plaza where people could spend time on self-reflection and self-expression. The GCPE student report for BCJC considered how underutilized spaces that already have a community and healing focus, like vacant land owned by churches, could be reclaimed to expand this creative wellness program.

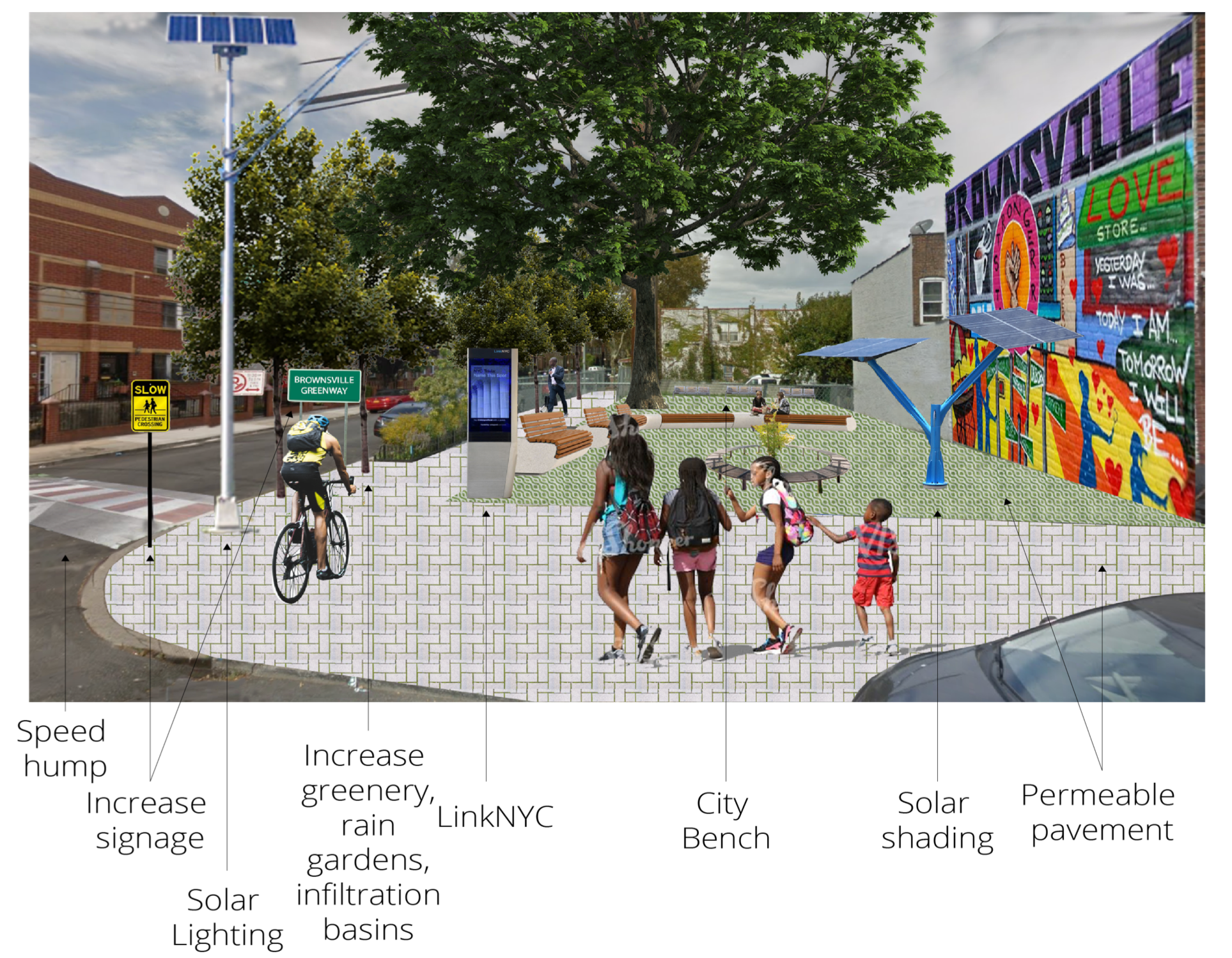

They also addressed how current major projects—including the B’ville Hub that is part of the new mixed-use Glenmore Manor development and will be the neighborhood’s first business center—could have a mix of financial and educational resources, such as a program teaching technology trade skills. A community-run solar energy coop and a community-run wifi network, meanwhile, could offer real-world applications for these skills. The students also provided strategies for advocating for a district-wide greenway where residents could travel and exercise safely beneath trees and alongside rain gardens, as well as ideas for encouraging street activity and economic development on Belmont Avenue such as advocating for traffic calming and small but impactful improvements like painting new crosswalks. Some of these projects could be realized in the coming months, others are more ambitious; all are part of a larger framework for keeping wealth and resources in Brownsville and empowering the community to drive its economic development.

“I am proud that our work helped to shape future planning ideas and processes for a real community in New York City,” Molnar said. “After all of the hard work, it is very rewarding to hear from a client that they will work to implement at least portions of the plan. Personally, in proposing a cooperative community solar project I learned a lot about solar energy in New York City and how it could make a huge difference in terms of community resiliency for Brownsville.”

In an article for the 2021 publication Teaching Urban and Regional Planning: Innovative Pedagogies in Practice, Yonder, Narciso, and Osorio note that the GCPE planning program “is rather unique being located in an Art and Design School, where innovative and creative practice is valued at least as much as academic research and publication, and studio pedagogy is emphasized throughout the Institute as a way of not just learning but creating knowledge.” They add that this approach was shaped by the legacy of the Pratt Center for Community Development which has been based at the Institute since the 1960s and partners with community groups on participatory planning that centers social and environmental justice as well as sustainability.

“As Ron Shiffman [co-founder of the Pratt Center and professor emeritus in GCPE] always says, ‘You have to go beyond,’” Yonder said. “The students are always encouraged to go beyond and maybe make some more visionary and creative recommendations for the long term along with ideas that could be implemented in the short term.”

Although the students will learn more about theory in their future coursework, the introductory studio offers a bedrock for their planning skills and putting the community first. The program also takes advantage of the diverse local planning needs in New York City—previous studios worked with groups in Sunset Park in Brooklyn and the Lower East Side—while considering how local issues reflect broader urban concerns. By working together with a community to analyze its strengths, opportunities, and weaknesses, the students have a foundation for their planning studies throughout their time at Pratt as well as first-hand experience for determining how they want to make a difference in the world.

Read additional stories in the Pratt Making a Difference series: School of Architecture Advocates for Climate Education with Pavilions & Projects on Governors Island and Architecture Students Explore How Aquaculture Could Transform Industrial Brooklyn with Oysters and Algae.