Celebrated artist Shaun Leonardo joined Pratt as the School of Art Visiting Fellow in fall 2018 and will remain on campus as the 2019 Project Third artist-in-residence. Fine Arts Visiting Associate Professor Jenn Joy sat down with him recently to discuss his practice, including projects such as Primitive Games at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York and Long Table: A Conversation at Pratt, and his work with Pratt’s community and students on campus. Leonardo will serve as moderator at Open Exchange: Belonging, the third annual School of Art Lecture Series event to be held on campus on April 9.

Jenn Joy: How do you imagine the distinction between image and performance in your work? What is the necessity of the performance?

Shaun Leonardo: Necessity is a good word. Both image-making and performance fit into each other as two different approaches toward the same goal and, from a personal standpoint, balance each other out in terms of what they require of me.

I’m looking for ways to slow down the viewer and more carefully guide where the audience is looking, so that I may translate their seeing into witnessing. We become desensitized—in the ways we do not look, in the ways in which we selectively look—so crucial information is being missed. How might I quite literally force someone, or invite someone, to sit in the trauma and more carefully read what this image might be saying? It’s in that slowing down that I feel we internalize an image more intently.

In the performances, I’m looking to see how information, which is lodged in the mind in intellectual rationalization, might move into a different place in the body. I often talk about the process in terms of embodiment. What happens when a news report lives somewhere else in the body? With the I Can’t Breathe series, which is concerned with the tragedy of Eric Garner’s killing, I asked myself how I might take a tragedy that is otherwise reduced in the media to an us-versus-them debate into a place where we more sensitively consider the humanity that was lost, to remove the possibility of a simplified argument, or even a rationalization of how and why this tragedy might have happened.

I asked people to go through a series of self-defense maneuvers, the first one being the actual, almost instinctive response that Eric Garner enacted when being accosted by police, which is a very simple, elegant movement of the hands. It is a self-defense technique that is then equated with resisting arrest. What immediately follows is a maneuver used by the NYPD, which they refuse to call a chokehold.

It’s later that I start to address what the participants are learning in terms of police violence. It moves slowly and gradually into this space where you’re paired with a stranger and alternating in the roles of aggressor and victim. When you are finally asked to place that chokehold and then receive it, the weight of it, the extremity of it, the lack of humanity, all of a sudden become a literal weight on your body. You can’t rationalize it. You can’t say to yourself, oh, this happened for XYZ reasons, or that it’s justifiable for these reasons, or that it just happened and allow yourself to move on. No. This is the loss of a person, of a human being. This is not justifiable on any terms.

The question that is not being asked is why this maneuver is an officer’s immediate response. The very next course of action was that chokehold, there was no other option in between. We start to understand the fear that directly leads to the death of a black or brown person.

JJ: Wesley Morris recently wrote an article in the New York Times asking if art now functions as a mode of social justice. If so, does it serve a particular morality where we can’t be uncomfortable or critical? I sense that the language of criticality and how it fits into politics, particularly around subjectivity and identity, feels really raw at this moment. I feel we’ve forgotten the work—limits and misfires included—of ’90s identity politics. Subjectivity wasn’t invented on Instagram.

So how do we train for or practice critical making differently? Performance feels important to these shifts: something about training, athleticism, and other ways of teaching presence that is not only showing up and having a feeling. How do you approach teaching this work?

SL: It does require training. I think we are more and more disconnected, mind and body. Many of the conversations I’ve been having around my work, particularly around the election, have to do with how we articulate fear through angst and through really abrasive language as a way of protecting oneself. It’s in that language that we isolate ourselves and move further and further away as communities. Why invest so much in bodily gesture and embodiment? It’s in embodiment that knowledge and truth are conveyed in ways that language just does not allow for these days. I often try to see ways to remove the voice altogether, so as to force people to articulate their positions through the body. Inevitably what we start to see is a fear that can be identified in the body. There’s something universal to that type of fear. In carefully reading that fear in another body, is the objective then finding a way to use fear more productively rather than again going to the default, defensive language that moves individuals away from one another? Can we actually use fear to pull each other closer together? The body tells a clearer story. It’s in that space that we connect.

JJ: You’re asking for a different model of witnessing? Or perhaps it is another strategy for study, as Fred Moten and Stefano Harney write, which is for them particular in relation to the institution of the university or by extension the museum? I’m intrigued by the ways your work deploys architecture in relation to this mode of practice. In the Guggenheim, the atrium frames a stadium of spectacle.

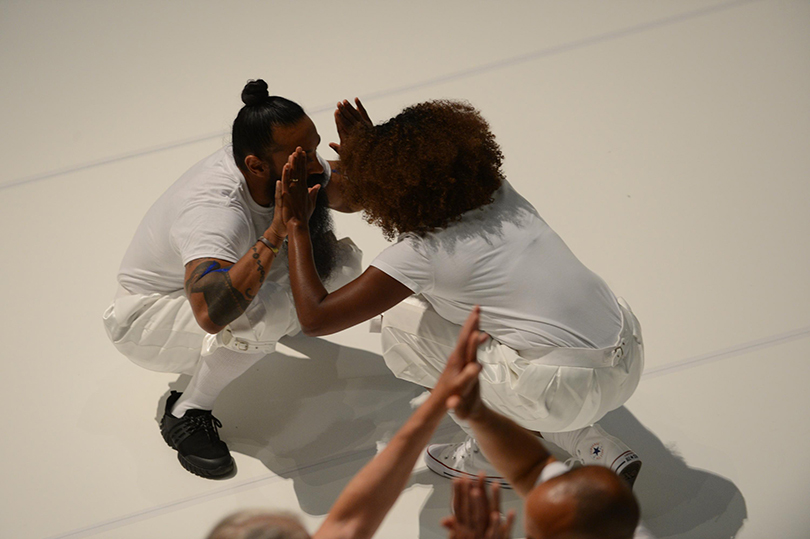

SL: It’s almost like orchestrating or choreographing that witnessing, utilizing the architectural space that is at your disposal. In terms of the Guggenheim project, I felt that I could use that architectural space, and the intimidation that it brings, as leverage to encourage the different groups’ participation.

People will give themselves over to participation, whether subconsciously or not, when they feel there’s a gravity in the space. Essentially all of my work is about reinventing platforms for discussion, but sometimes it requires a performative gesture to allow someone to insert themselves. If you ask someone to speak their mind and provide a podium, it’s not going to happen. Sometimes what it requires is a little deception. What you’re asking them to commit to is an unknown, but in that staging you’re also saying that there is no expertise required. You’re bringing only yourself, and you already have the capacity to contribute.

What was beautiful about many of the conversations I had with audience members afterwards [at the Guggenheim], was that so many individuals anticipated violence and waited for a conflict to erupt right away. They then had to question why they anticipated and almost desired aggression—it has everything to do with how they were experiencing the environment as a gladiatorial arena.

JJ: Is there a way that you bring back language after the fact?

SL: I often look for the return or reshaping of narratives using different language. In terms of the Guggenheim project, I honestly think that is the promise of the work’s evolution. Now that the participants have gone through this process where they sought out humanity in one another, how do they get to a place where they actually do revisit language and speak about gun violence face-to-face? The intention is not to reach resolve, but to see if disagreement might bring some consensus.

That was always my motive: to bring divisive groups to the table, to disarm them of their positions, to have this other bodily experience. I would like to see what then happens when we return to language.

JJ: With the Long Table project at Pratt, it feels that language is returning. Is there also a physical dynamic you’re working toward?

SL: I think there is a way in which the suggestion of the Long Table performance breaks down hierarchy. In its format, while you start with 12 seated people, at any point anyone could tap out an individual and assume that seat. What’s essentially built in is the idea that someone with authority, in a day-to-day context, could very well be tapped out by a student. I’ve also witnessed someone who was taking up too much airtime get tapped out. The typical format of a town hall, lecture, or classroom does not create the equalizing effect that’s necessary to have very difficult conversations.

I don’t think, as a community, Pratt is ready to dislodge itself from language. However, as a faculty, we recently discussed how in our students the inability to articulate a position has resulted in self-silencing, and in peer-to-peer shaming. It’s our duty as faculty to think about reinventing platforms of class discussion.

The reason why I moved to this kind of performative conversation is that in the lead-up, I decided to have one-on-one conversations with various corners of campus, with the starting point of having people define what Pratt community means to them. How would you define “Pratt community” to me? As a person being tasked with the challenge of creating these platforms, but also thinking about how Pratt community might extend itself outward, I have to first ask, who is the Pratt community?

Strangely, but maybe not surprisingly, that question almost inevitably, without my prompting, transitioned to an idea of safety. I think it has a lot to do with the architectural boundary and psychological boundary that this campus has—that isolates it.

I started having brief conversations with everyone from individuals in the executive offices to campus safety and facilities, the student body, faculty, and staff, as an instigation to ask how meanings—of the words safe, safety, the overutilized term “safe space”—shift depending on whom you’re talking to.

How do we have a frank, open and willing conversation about the ways that we don’t agree on these definitions to then develop the questions that will start to define “community”?

JJ: Does the association of an artist with individuation and voice, as singular, also complicate a definitional and actual sense of collectivity?

SL: I think as an artist I can be a catalyst to this type of nonhierarchical conversation. It’s in considering each definition as equal and valid that you start to actually get a more collective understanding of what is important to this community. We’re saying that it is not mutually exclusive to have a protected, isolated, creative study space, and yet still belong to something larger. That’s what I want to instigate, you know?

JJ: Holding all the meanings feels so important. I find myself searching in texts for ways to parse something of art’s political efficacy. Writing after the election in Artforum, Amy Sillman points to Agnes Martin’s show at the Guggenheim and says: “We could see it better—rather than asking why Martin was making abstract paintings of grids during times of political crisis, the work beamed out its stoic, clear-headed, purposeful, classical, stubborn, weirdness … good qualities even in those extreme times.”

SL: I was just having this rather charged conversation with my students and reflecting back on how, for many young people, subjectivity has almost become an excuse for not considering the broader political perspectives that might surround one’s work. As an act of not owning up to a larger politic, a student might say, well, this is based on my personal experience. What they’re actually arguing is that one can hold onto a singular discourse while not being accountable for how someone else might see the work. That to me is deeply problematic.

JJ: I think about how autobiography and experience become conflated and definitional. Saidiya Hartman speaks so beautifully to this when she explains her interest in autobiography is not about solipsism, but a way of marking concrete experiences as they lean into the historical present. I wonder, too, what we mean by criticality now? Has the language of criticality shifted? Is it generational?

SL: I pose that question to my students as well. I try to suggest that even in the ways we articulate our own subjectivity or autobiography in a work, everything we place in a work points to a consideration, or lack thereof, of all the interpretations that might surround our personal starting point. How is it, even in an insular studio practice, that we hold ourselves accountable to just one of those interpretations? The question of whether that is important or necessary is really challenging for some of these students.

JJ: Reckoning with accountability is vulnerable. How do we construct spaces or encounters for vulnerability to happen? Particularly in relation to the questions of safe and safety, how do you move through language?

SL: If we can’t create the rituals and platforms for belonging, we’re cheating these students. If what our promise of safe space entails is a degree of protection by separation, then they’re leaving unprepared for what the world is going to offer them. We’re also cheating them out of what actual community should entail, which is a place to experience the totality of life in all of its range of emotionality.

How do we build that in? I don’t know. I can’t solve that problem. [Laughter] I do think that there are ways through trickery, through nonhierarchical arrangements, that people can be invited to really contend with one another and each other’s views. We make so many assumptions about what a person needs and about someone’s worldview.

In all my work, I want to find those places where we give ourselves over to vulnerability. It’s not creating vulnerability. The vulnerability is already there. How do we allow someone to touch another person, or hear another person, or just exist with another person? Sometimes it requires a performative move or spectacular platform to create a world that is just slightly askew for someone to submit to an experience, you know?

It goes back to training. If I want to impart anything in my short time at Pratt, it’s that it is the institute’s responsibility to create a situation where someone can have a whole experience or consider themselves a whole person.

Images: (main image) Primitive Games – performance, 1 hr. at Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY, 6/21/18. Photo by Paula Court; (inset) Primitive Games – performance, 1 hr. at Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY, 6/21/18. Photo by Enid Alvarez