Think bees and one familiar set of images, habits, and behaviors likely comes to mind.

But this is scratching the surface of all that could be understood about some of nature’s most industrious workers—vital knowledge that architect Ariane Lourie Harrison, Visiting Associate Professor and Coordinator of the MS programs (Architecture and Urban Design) at Pratt, is working to develop.

Everyone knows the honeybee, but many may be surprised to learn that this iconic insect originally came to the US from Europe, or that it’s just one of about 20,000 species of bees worldwide, with the vast majority of the native species in North America being “solitary bees.” These types of bees, which don’t have a queen or operate as a hive, making them challenging study subjects, are critical to agriculture and the ecosystem as a whole, as most flowering plants on the planet need pollinators to reproduce.

And the honeybee, for all the golden deliciousness it produces, does very poorly compared to solitary bees when it comes to pollinating American native plants such as pumpkins, cherries, blueberries, and cranberries. Solitary bees, on the other hand, pollinate nearly 80 percent of flowering plants and approximately 75 percent of fruits, nuts, and vegetables grown in the country. And possibly the best attribute of solitary bees is that, unlike honeybees, they are nonaggressive. Many don’t even have stingers.

To study these enigmatic insects with the hope of understanding and improving their role in the planet’s ecosystem, Harrison has created the Pollinators Pavilion, a striking dome-like oval structure made of concrete and covered with spiky protrusions.

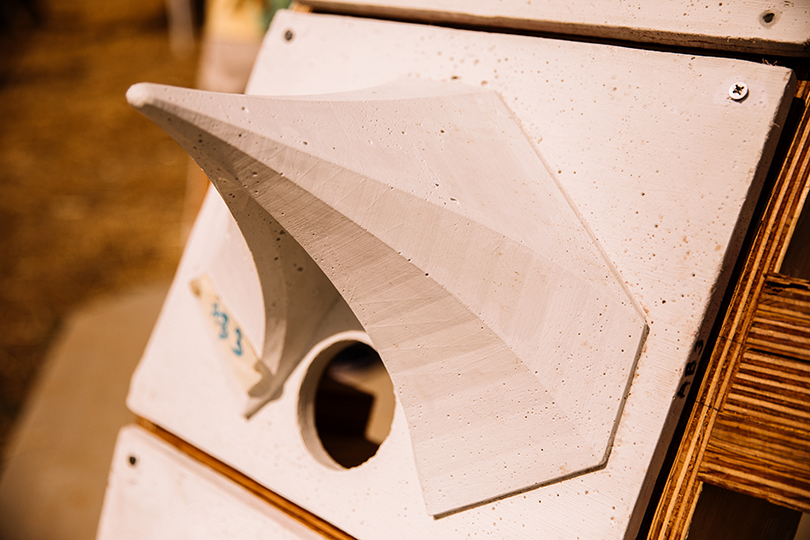

Ariane Lourie Harrison demonstrates the placement of the Pollinators Pavilion’s nesting tubes, which will be protected from the elements by each concrete panel’s protrusion. Photo by Lily Landes

“Our interest here is in creating a way to document how these solitary bees live,” Harrison says. “So the Pavilion is an ‘analogous habitat,’ as well as a research field station and visitor center.”

With a footprint of 18 feet by 14 feet, and rising to 9 feet tall, the Pollinators Pavilion offers inhabitation for up to 4,000 solitary bees in over 300 panels, each having a hole filled with a bundle of bamboo shoots that mimic the natural cavities where solitary bees deposit their larvae in the wild. The panels, which are made of Ductal®—an ultra-high-performance concrete (UHPC) technology that parent company LafargeHolcim invented—were fabricated at Ductal’s workshop in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. Ductal contributed both material and, as Harrison notes, deep expertise: Her team worked closely with UHPC consultants Kelly Henry and Andrew Pinneke.

The Pavilion was constructed this past summer on the grounds of Old Mud Creek Farm—a sister operation to Stone House Farm, a 2,500-acre model of regenerative organic agriculture in New York’s Hudson Valley. The Pavilion itself is situated on an idyllic little hill with a 360-degree view of all the farm’s fields, as well as vistas of the picturesque Catskill Mountains.

Various species of bees in the genus Osmia, commonly known as mason bees, are among the types of pollinators that may begin nesting in the Pavilion next spring. Images sourced from USGS Native Bee Inventory and Monitoring Program.

The form of the Pavilion was inspired by the compound eyes of the bees it’s meant to attract. Seen under a microscope, bees have tiny hairs that grow out of the lenses of their eyes. These hairs are believed to be used to detect wind direction as the bees head out to find flowers to pollinate. Harrison incorporated that element into her design, where the pointed form of each panel not only mimics the hairs on the bee’s eye, but serves as both a rain canopy and storage space for a solar-powered monitoring system that includes an endoscopic camera, a motion sensor, and a microprocessor.

“Each panel is a way to passively document the comings and goings of the solitary bees,” Harrison says. “When the bee breaks the beam of the motion sensor, the camera turns on, and we get a flow of images.”

The images collected by each panel are then fed into a database for a machine-learning system to identify the species without harming the bee. The initial image library used as the foundation for the machine learning was derived from a collection of solitary bees at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

“Post-human doesn’t mean we’re getting rid of humans . . . it just means we’re moving humans away from the center of our inquiry as architects.”

Ariane Lourie Harrison

For Harrison, this unique amalgam of art and science started with a question that challenges the conventions of human-centric architecture, while also suggesting a larger role for architecture in environmental activism in the Anthropocene—the geologic age in which some scientists believe humans are the primary driver of change: How can humans build with and for other species?

Architecture as a field has always focused on humans, but Harrison notes that we’re only one species among an estimated 10 million—of which fewer than 2 million have been identified. We’re discovering new ones each year. That insight has driven Harrison’s years-long interest in what is called “post-human architecture.”

“Post-human doesn’t mean we’re getting rid of humans,” Harrison says, “it just means we’re moving humans away from the center of our inquiry as architects.”

Harrison’s Brooklyn-based architecture firm, Harrison Atelier, which she cofounded with her partner Seth Harrison, has made previous attempts to answer the question at the heart of post-human architecture before the Pollinators Pavilion, the most recent being a project called The Birds and the Bees, completed in early 2016 and installed at The Frank Institute @ CR10 near Hudson, New York. The modular wall panels of that structure—which resembles an oversized antique room divider—were designed to house small, cavity-nesting birds and hole-dwelling bees. The installation had a brief exhibition, but when Harrison reinstalled it in her garden at home, some birds actually built nests in some of the panels.

“It felt like the birds were fine with a little hollow space,” Harrison says, “but for the bees we realized it was a lot less straightforward. We realized that there were certain conditions, like shelter from the rain, that they needed.”

At that point, Harrison decided to bring in a science advisor to get a better sense of what else solitary bees might need in a nesting site. That’s when she turned to Kevin Matteson, Director of Graduate Programs for Social and Ecological Change at Miami University in Ohio, who had done his dissertation research on bees and pollination in the Community Gardens in the Bronx and East Harlem before doing his postdoctoral research in Chicago.

“There’s some literature on this area,” Matteson says, “but in terms of published studies of what materials and hole dimensions you should use to attract certain species, there isn’t a lot.”

Matteson says there are a few studies that show that with a four-millimeter hole, for example, you’re likely to get a certain type of predatory wasp, but if you go to eight millimeters or more, you might get mason bees—a species of solitary bee. There also needs to be a selection of certain flowers planted nearby, because different species of solitary bees are attracted to different species of plants, and only fly so far to get to them.

“We’ll see what it actually attracts, which is what I’m most interested in,” Matteson says of the Pavilion, “but it’s also going to draw some public interest and awareness about the issue of native pollinators, and that’s really important.”

“We’d like to use this project as a model for rebuilding those populations that are essential to biodiversity and, ultimately, our survival.”

Ben Dobson

The Pollinators Pavilion developed by way of a cross-pollination of ideas and expertise, a continuous interdisciplinary dialogue that has deepened the project’s resonance. It all began with a fortuitous encounter between an architect, an artist, and a lifelong farmer.

Francine Hunter McGivern, a native New York artist who founded The Frank Institute @ CR10—a 15,000-square-foot space for conceptual artwork and a functioning cultural center—is the one who brought the architect and the farmer together.

“I really like the idea of collaborating with people who enjoy the feeling of being equal,” McGivern says. “Everyone brings their skills and vision to an idea, and then its manifestation comes from everybody’s commitment to making it happen.”

McGivern had previously hosted two of Harrison’s exhibitions at The Frank Institute, which is located about five miles from Stone House Farm, where Ben Dobson, a leader in regenerative farming practices, has been the general manager for the past six years.

Dobson had come to The Birds and the Bees exhibition, where McGivern presented the idea of the Pollinators Pavilion. Dobson was instantly receptive to the idea.

“From an ecological perspective and a beauty perspective, I was all for the project,” Dobson says. “It really fits in well as a new habitat for insects we’re trying to bring to the farm.”

“We’d like to put several pavilions around the farm to highlight the plight of wild pollinators because they’re so important to our ecosystems and agriculture,” he says, “and use this project as a model for rebuilding those populations that are essential to biodiversity and, ultimately, our survival.”

Harrison would also like for the intent behind the Pavilion project—to create more protected habitats for solitary bees and raise awareness of their role in the ecosystem—to grow beyond Dobson’s model farm, to Americans’ backyards.

“We’re very interested in this partnership with LafargeHolcim,” she says, “because there is an idea that we could develop a panel system that we can sell at Walmart, for example, and everyone just hangs up a few panels and it’s no big deal—these bees don’t sting, they’re great neighbors.”

In addition to the collaboration with McGivern and Dobson, Harrison couldn’t have accomplished something as ambitious as the Pollinators Pavilion without the support of Pratt, where the project received an award at the 2019 Pratt Research Open House.

“The school has such an amazing research agenda,” Harrison says, “so there’s a sense of real support. It’s nice to be part of a school where your research is actually valued.”

Harrison also credits the contributions of a diverse team of designers at Harrison Atelier with bringing the project to life, including recent Pratt alumni Eileen Xu, MS Arch ’18; Nai-Hua Chen, MArch ’18; Zongguan Wang, MS Arch ’18; and Yuxiang Chen, MS Architecture and Urban Design ’18.

Yuxiang “Riccio” Chen, who was a student in the Graduate Architecture program Harrison currently coordinates, said he was impressed with Harrison’s commitment to post-human architecture. His role in the project was to make sure all the panel components fit together so that they could be installed on the farm site properly.

“It’s very easy to design something complex or even weird on the computer with the help of digital technology,” Chen says, “but how to realize those forms in reality is a totally different thing—it’s one of the most interesting and memorable experiences I had from this project.”

Chen says he drew on his experience as a monitor at the Consortium for Research & Robotics, a center for collaborative research at Pratt located at the Brooklyn Navy Yard that is home to the city’s largest industrial robot.

“I had access to a lot of different architects,” Chen says, “helping them to fabricate their projects’ components and make sure they could be installed in real life. Without that experience, I don’t think I could have finished the optimization of the Pavilion structure and its construction.”

Since its completion this summer, the Pavilion has drawn community interest, but Harrison doesn’t expect much pollinator activity until the spring, because the nesting season for bees begins in April.

As the experiment progresses, its contribution to the scientific knowledge of our native pollinators will take time to unfold. In the meantime, Harrison plans on securing grants for the project so that she can continue to monitor the site and build the machine learning, which will likely be a two-to-three-year research cycle. In August, the project received significant support in the form of an AI for Earth grant from Microsoft, given to advance projects that use artificial intelligence to address sustainability-related issues such as biodiversity. The grant will enable Pollinators Pavilion to use Microsoft’s Azure cloud-computing tools to build the database of pollinator images.

As Harrison continues to concretize her abstract architectural designs (quite literally) with the Pollinators Pavilion, she also continues to realize her vision of the architect as less an isolated creator of beautiful forms for humans, and more a collaborator with both human and nonhuman species.

“That’s my ambition for architecture,” Harrison says. “To design for the coexistence of multiple species, and in doing so, make a profound contribution to the environment.”