Who are the strong, pathbreaking women who embolden today’s emerging artists and designers? Bad Girls in Literature, Art, and Music, an elective in Humanities and Media Studies, bridges the past and present of women, creativity, and nonconformity in the arts. Developed by Laura Minor and Ira Livingston and taught over the past year by Maria Damon and Adrian Shirk, BFA Writing ’11, Bad Girls highlights creative trailblazers who have broken barriers and opened opportunities with their art—and how their work still challenges audiences. The class also aims to introduce new “bad girls” to the canon, with students presenting on the life and work of women practicing across a range of fields and mediums. Read on to explore how nine recent students of the class spotlight the iconoclasts who inspired them.

Leia Bradley, BFA Writing ’20, Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald (1900–1948)

Leia Bradley spotlighted Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald, “suffragette, flapper, and artistic revolutionary . . . the ultimate rebel of her time,” whose accomplishments, often overshadowed by the mythology around her storied, tumultuous marriage to F. Scott Fitzgerald, included dance, painting, and writing.

Zelda felt stuck, and found her freedom through her words, just as I intend to do. . . . As an artist, she inspires me to gorge myself on romance and passion, to never let go of the people and places that remind you of who you are and where you want to be.

All I want is to be very young always and very irresponsible and to feel that my life is my own—to live and be happy and die in my own way.

—Zelda Sayre, letter to F. Scott Fitzgerald

Hearing her words echo in my bones evokes incessant, dauntless memories belonging collectively to all women, with their dreams outstretched before them, waiting to be discovered. . . . I carry Zelda with me like a reminder to stay ambitious, scandalous, and wild in life and in creative ventures, the paradoxical lesson being to escape the calamity of her fate.

—excerpted from presentation and words by Leia Bradley

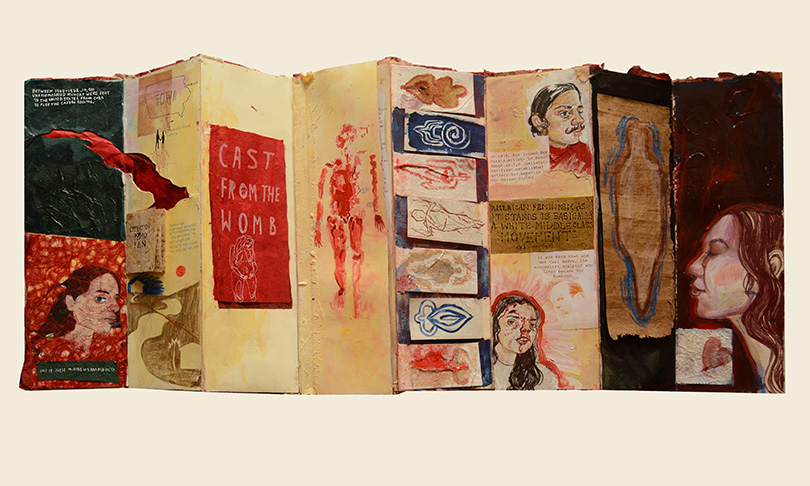

Amy Bravo, BFA Communications Design ’19, on Ana Mendieta (1948–1985)

Amy Bravo presented on artist Ana Mendieta, whose work spanned film, photography, sculpture, drawing, and installation.

Ana Mendieta is not only a pioneer in women’s performance and video art, but a pioneer for Cubans making work about diaspora in America. Though her time as an artist was tragically cut short, her work continues to impact women like myself to make work about cultural displacement and personal identity in reference to the places we come from.

On viewing Mendieta’s video piece Corazón de Roca con Sangre, one of the works in Mendieta’s Silueta series of earth-body works created from 1973–77, at the Brooklyn Museum: Ana fills a silhouette of her own body in the mud with a rock and red pigment, then lies facedown in the space she’s carved out. . . . I watched the video as it looped about seven times, and cried quite openly in public for a sister from another life, lost from the same island. My experience with this piece marks the only time I’ve ever, in an art institution, felt truly represented and seen.

Ana’s legacy is one that lights a fire in those who can see themselves in her, who understand what it’s like to live in exile, to carry the weight of an entire island on your shoulders, to miss a place you can never return to, or maybe you’ve never been to but somehow belong to.

—excerpted from presentation and words by Amy Bravo

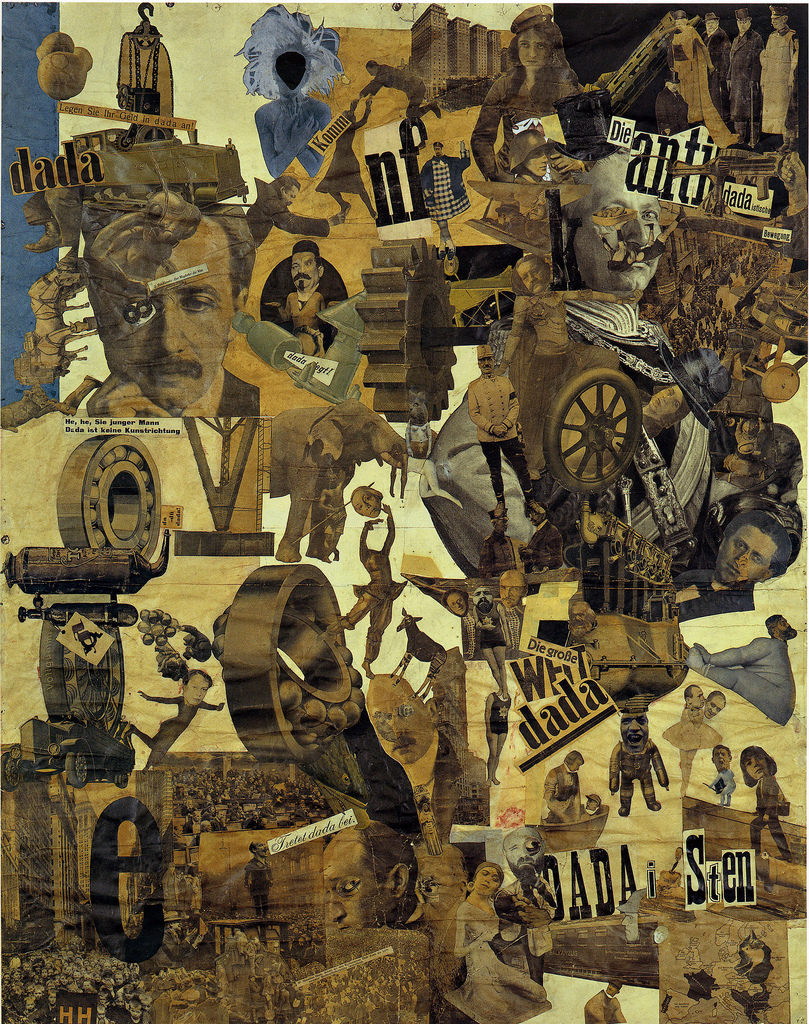

Tyhe Cooper, BFA Writing ’21, on Hannah Hoch (1889–1978)

Tyhe Cooper presented on Hannah Hoch, “a hugely influential, boundary-breaking collage artist.” Cooper worked to both illuminate the artist’s work and write into her own “reconnection with femininity and womanhood.”

Ever since I discovered her work, I have been in awe of Hannah Hoch and her work’s existence in the art world of her time. She was able to break into a very male-oriented field and collective (she was the only woman in Berlin Dada) and create thoughtful, provocative, feminist, and feminine art, without catering to any given demographic.

You, craftswomen, modern women, who feel that your spirit is in your work, who are determined to lay claim to your rights (economic and moral), who believe your feet are firmly planted in reality, at least Y-O-U should know that your embroidery work is a documentation of your own era.

—Hannah Hoch, Embroidery and Lace (1918)

Hoch’s work, and her personhood, took a fierce stance against gender roles and the oppression and lack of respect associated with femininity. She presented herself, and her artwork, as a symbol of what she felt womanhood ought to be: self-sufficient, strong, striking, subversive of all roles it was told to play. . . . I am most interested in the way that she used the style of the male collage artists of her time to portray an opposing viewpoint. Hoch’s fragmentation of women’s bodies in her collages finds a way to fight back against, and present the detriment of, that very fragmentation in the work of her male peers.

I have been attempting to permit myself to be varied and nuanced in my personhood and womanhood, as well as in my art. . . . The permission we give ourselves to exist in ways that challenge norms, and sometimes are highly normative . . . is something that I have been working to express in my work.

—excerpted from presentation and words by Tyhe Cooper

Tené DeVeaux, BFA Writing ’20, on Lena Waithe (b. 1984)

Tené DeVeaux explored the creative emergence of contemporary writer and performer Lena Waithe, whose credits include the 2014 film Dear White People, which Waithe coproduced; Master of None, the Netflix series she wrote for and played a supporting role in as Denise, the protagonist’s best friend; Steven Spielberg’s 2018 film Ready Player One; and The Chi, a Showtime series Waithe created, now in its second season.

I chose Lena Waithe because finding someone who not only presents like me, but also creates a space for those like me, was so rare. . . . Her mere existence meant a lot to me specifically, since she’s a black, gay, masculine woman who was able to build a media presence mostly around just being herself and retelling her stories.

I don’t think my story as a queer black woman is so crazy and random, but it’s very specific. Especially in my community, there’s a lot of images in the media or social media about, ‘Oh, this is what a black lesbian is and what she looks like.’ I thought the more specific we could be about it, the more interesting it could be.

—Lena Waithe

In season 2 of Master of None, Lena was offered the opportunity to co-write an episode about her character Denise’s coming-out story. The episode led to Lena’s first Emmy nomination for outstanding comedy writing . . . and she won. Lena says that the victory was “bigger than herself” and is considering mentoring young African American writers in the future, “figuring out where they are as a writer, what they actually need, and helping them get it.”

—excerpted from presentation and words by Tené DeVeaux

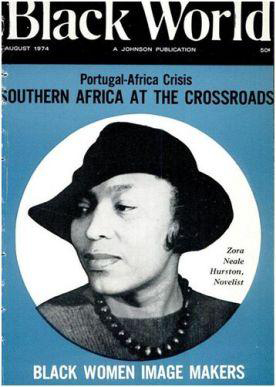

Bridget Hawkins, BFA Writing ’19, on Zora Neale Hurston (1891–1960)

Bridget Hawkins presented on Zora Neale Hurston, novelist, folklorist, playwright, and anthropologist committed to preserving black culture—“a literary pioneer and a rebel.”

When I first read Zora Neale Hurston’s work as a high school student, I felt an immediate connection to her, as a writer and as a black woman: she and I existed in a shared literary tradition. I highlighted her to honor that connection, and to express the awe I have for her work.

I have the nerve to walk my own way, however hard, in my search for reality, rather than climb upon the rattling wagon of wishful illusions.

—Zora Neale Hurston, letter to friend and fellow writer Countee Cullen

In a world that told her to feel disgusted by her color and her gender, Hurston wrote proud black women into her novels and plays that spoke lyrically about their sexual desires and sense of beauty. She was a woman pioneer of literature and film, pushing the boundaries of what the written word could accomplish, a researcher and folklorist who dedicated her life to celebrating the intricacies and beauty of black cultures—and because of that, she was erased from literary canon.

Even though her most successful novel, Their Eyes Were Watching God, is more commonly known now, the full breadth and ambition of her work are rarely acknowledged. . . . Against great societal forces, her female characters maintain their strength, sexual desire, and agency. . . . Zora Neale Hurston circumvents oppression by denying her oppressor a voice in her work. She models the power of Bad Girl disobedience—full of a prideful black feminine energy taken up now by generations of her literary daughters.

—excerpted from presentation and words by Bridget Hawkins

Hope Morrison, BFA Sculpture ’19, on Patty Chang (b. 1972)

Hope Morrison presented on contemporary artist Patty Chang, whose performance-based work often “tests the endurance of Chang’s own body” toward “a physical and emotional sacrifice.”

I am inspired by Patty Chang because she navigates the world in an inherently feminine way. Although her strength and artistic power far override her female identification as an artist, Chang is a great influence for other feminine artists because she does not need to explain her own femininity; she performs it flawlessly.

Her recent and most ambitious project, The Wandering Lake (2009–2017), features photographs, videos, and sculptures, an exhibition at the Queens Museum in New York, and her first publication, The Wandering Lake (2017). These documentations refer to the past and the ephemeral present of her travels to Newfoundland, Uzbekistan, Shangri-La, and the Xinjiang region of China. She navigates these locations on multiple trips over an eight-year period, using her body as knowledge and reference to her travels. This makes for a transformative experience that evokes the female body and the navigation that comes with it, as if the body were a landscape.

She makes art that is about the female anatomy and the societal obstacles that we must navigate physically and emotionally as artists. . . . Patty Chang rewrites what others have not solely through her performance. And the performance is persistent, it is inherent in all female bodies. The act of performing is the act of living.

—excerpted from presentation and words by Hope Morrison

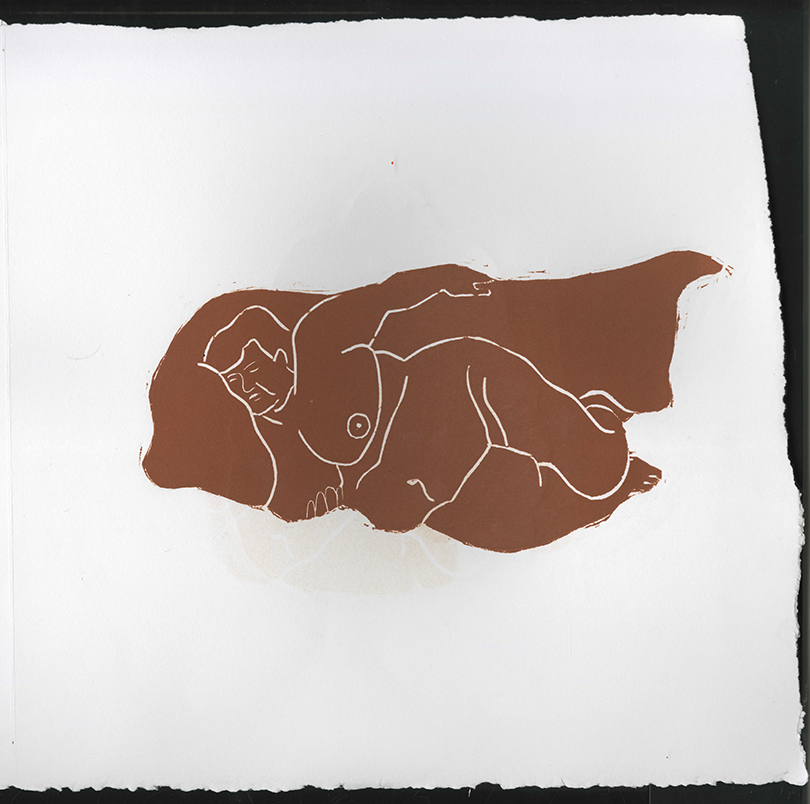

Lina Ramos, BFA Communications Design ’19, on Nancy Spero (1926–2009)

Lina Ramos highlighted Nancy Spero, painter and a founder of A.I.R. Gallery, the first women’s cooperative gallery, established in 1972.

Nancy Spero dedicated her work to redefining the image of woman into a symbol of power, freedom, and energy; gone were the interpretations of woman as object or victim. Spero’s revival of ancient female figures mixed with current images really inspired me to do the same, but looking at art history through the lens of the fat woman.

I’ve always sought to express a tension in form and meaning in order to achieve a veracity. I have come to the conclusion that the art world has to join us, women artists, not we join it. When women are in leadership roles and gain rewards and recognition, then perhaps ‘we’ (women and men) can all work together in art world actions.

— Nancy Spero

Nancy Spero’s work was aimed at changing perspectives, with a range of subject matter and mediums. Her early work started as painting subtle figures in monochromatic palettes [and] painting about the Vietnam War and Holocaust. Eventually her medium changed to printmaking and collaging, using female figures from art history to “[rewrite] the imaging of women through historical time.”

Spero also began to reject a canvas . . . moving her women figures onto the walls, floors, and ceilings. . . . She inked and stamped them on galleries and buildings, her figures dancing and leaping without the constraint of a page. She freed them while freeing herself of the constraint of the male opinion.

Ramos on her prints inspired by Spero: Carving these women out of linoleum allowed me to really appreciate the curves and voluptuousness of the fat female form and helped me to get over some body issues of my own.

—excerpted from presentation and words by Lina Ramos

Emma Stephens, BArch ’20, on Denise Scott Brown (b. 1931)

Emma Stephens presented on Denise Scott Brown, architect, planner, designer, author, and principal of Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, who spurred the seminal course Learning from Las Vegas and coauthored the text of the same name, and contributed to Pritzker Prize–cited works such as the Sainsbury Wing of the National Gallery on Trafalgar Square in London.

I chose Denise Scott Brown because she has been particularly outspoken about the way gender affected her career; her story has become a rallying point for women in architecture. I felt that it was particularly important to highlight her work because it is so often misattributed to her husband.

One would be remiss to find a contemporary architect who was not in some way aware of her work. However, because of her marriage to her creative partner, Robert Venturi, architecture as an institution has long minimized or overlooked her contributions.

Some people said, ‘She married the boss and thought she could get ahead.’ . . . But if anyone was the boss, I was. We really were colleagues and we taught together. It was a very, very wonderful collaboration for both of us.

—Denise Scott Brown

The misattribution of Denise Scott Brown’s work became especially visible in 1991, after her husband was individually awarded the Pritzker Prize. . . . The jury acknowledged that their work was largely inseparable and yet individually recognized Venturi.

Throughout her long career, Scott Brown has been vocal about the sexism she experienced as a practicing architect, particularly critiquing the “star system” and supporting what she calls “joint creativity.” Denise Scott Brown is often called the grandmother of architecture; I would like to suggest instead that Denise Scott Brown is architecture’s most prominent Bad Girl.

—excerpted from presentation and words by Emma Stephens

Rosie Waring, BID ’19, on Eva Zeisel (1906–2011)

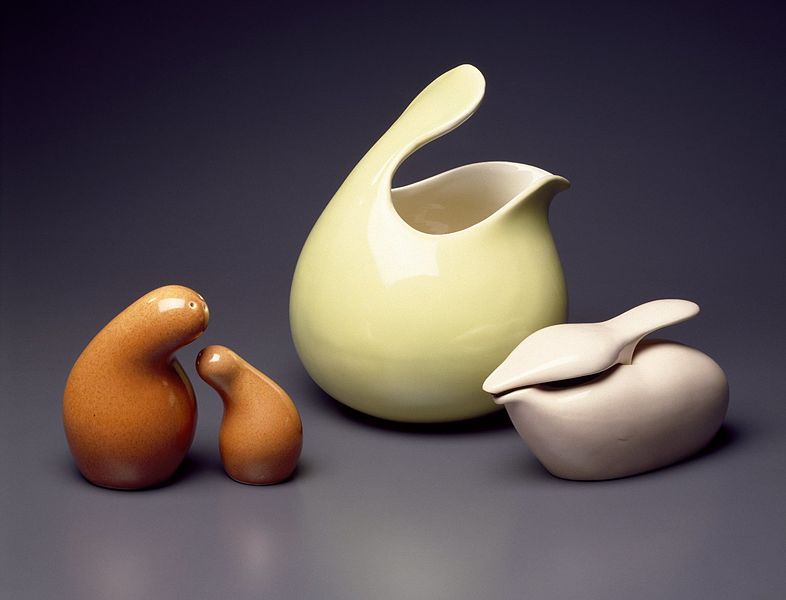

Rosie Waring presented on Eva Zeisel, designer, ceramics artist, writer of poetry, and educator at Pratt in the Industrial Design program from 1939 to 1953.

I was able to meet Eva Zeisel’s daughter, Jean Richards, and visit Zeisel’s studio in New City, New York. . . . Seeing her studio in person was incredible, and knowing a woman in the early 1900s achieved a professional career in design was inspiring to me.

Zeisel created a design language and philosophy which has outlasted her physical presence. She studied painting, professionally designed ceramics, and personally defined the art of beautiful form.

The grace and simplicity of her designs seem easy to outsiders; this is only because of the work she does to study every surface. Any artist knows the challenge in simplifying an idea. Her designs are a stunning example of this skill.

Living in Moscow in 1936, Zeisel was imprisoned after a former colleague from the Lomonosov Imperial Porcelain Factory gave her name during an interrogation: The time spent in Leningrad had a remarkable impact on her work. Because of this hardness and cruelty, confusion and hatred, a part of her was intensified. The romantic and loving part of her, the side that made beautiful poetry and wanted everyone to be comforted and cared for, was intensified.

Her works are not meant to stand alone, and tended to nest, or come in pairs and sets. The way she describes her works is incredibly human. She feels them as beings, little spirits, and breathed life into every form she created.

—excerpted from presentation and words by Rosie Waring

More celebrations of Women’s History Month at Pratt are happening on and around campus in March, including Women’s History Week, which begins March 18 with a kick-off event featuring Pratt Institute President Frances Bronet. Hosted by the Pratt Community Engagement Board, Women’s History Week will include a curated student art show at the Student Union, film screenings, a Pratt Day of Service, and more. Find the full schedule of events. Pratt Institute Libraries is hosting a full-day Art + Feminism Nonbinary and GNC Wikipedia Edit-a-Thon in the Brooklyn campus library.

Images: Accordion book by Amy Bravo, with text by Bravo and quotes from “Where Is Ana Mendieta?” by Vanessa Bermudez; Detail of accordion book by Amy Bravo; Hannah Hoch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany, 1919; Cover of the August 1974 issue of Black World magazine featuring Zora Neale Hurston; Relief print from accordion book by Lina Ramos; Red Wing Pottery pieces from “Town and Country” collection by designer Eva Zeisel (glazed earthenware, ca. 1945) (license).