On a bike path in downtown Brooklyn, a half-hour walk from Pratt Institute and just off a nexus of streets that converge at the Barclays Center, a green sign with the logo of a bike says Weeksville, with an arrow pointing east. The few buildings that remain of the historic self-sustaining Black community founded in 1838—shortly after New York State’s 1827 abolition of slavery—are a twenty-minute bike ride away and the signage is new. It underscores Weeksville Heritage Center’s recent inclusion in New York City’s esteemed Cultural Institutions Group, an honor that increases access to funding as well as cultural cachet.

For a pair of Pratt faculty members teaching architecture, Jeffrey Hogrefe, professor of humanities and media studies and cofounder of the Architecture Writing Program, and Scott Ruff, adjunct associate professor of architecture, the new designation has its pros and cons. Co-creators of the project Pratt Weeksville Archive—an oral history initiative developed in collaboration with the Weeksville Heritage Center, community partners, and Pratt students—Hogrefe and Ruff aim to contribute to the recentering of the area’s Black history and culture in the public imagination, and support its present-day residents in activating the story of this place for generations to come.

Founded by free persons and formerly enslaved persons, Weeksville once comprised seven civic institutions, actively participated in city government, and served as a destination on the Underground Railroad. This rich heritage makes it a vital resource for imagining the future, asserts Hogrefe. “We feel that once it’s realized the extent to which this self-sustaining 19th-century community really flourished, it can become a model for a 21st-century self-sustaining Central Brooklyn,” he says. “It has a lot to offer us in the radical imagination.”

Scholars from Pratt have played a part in clarifying Weeksville’s past since the former settlement was brought to light five decades ago. Housing stock from the former community was documented in the 1970s as a result of an aerial survey by Pratt Institute professor James Hurley and pilot Joseph Haynes in 1968 and the efforts of local activists. Weeksville has slowly regained historical footing in the area ever since.

The city’s interest in Weeksville advances attempts to determine a set of geographical boundaries for the area, markers of a thriving, aspirational Black utopia that was lost to forces of anti-Black violence, including redlining and urban renewal, and erased from maps by the end of the 19th century. However, as Ruff and Hogrefe note, future ownership of the name and the place is precarious. “If you look at the histories of Black settlement in the US, it’s a constant struggle with anti-Black violence. Now, gentrification is possibly the most silent and deadly of all because it doesn’t announce itself. It’s happening all over the US.”

Ruff underscores the urgency. “Real estate people have started to co-opt the term Weeksville. Two years ago, I could go on Google and there was no Weeksville. Now, Weeksville is designated as a place and they’re using it as a way to market it. It’s kind of a foot race to see who can capture the term.”

In their work, Ruff and Hogrefe consider how an active archive of oral history and critical ethnography might ward off the damaging effects of such interests. “It is up to us to encourage the stories of those who know the place and others like us to make it clear that this is a historic space that needs to be protected from predatory development,” notes Ruff.

To that end, students in Pratt’s undergraduate architecture program and graduate library and information science program have been instrumental in developing the Pratt Weeksville Archive oral history and critical ethnography project. Launched in the fall of 2020 and supported by a Taconic Fellowship from the Pratt Center for Community Development, the project has engaged students from the undergraduate architecture research studio Connecting to the Archive, which Hogrefe and Ruff teach, and Research Assistants, an elective course for fourth- and fifth-year architecture students to work with a faculty member on an approved research topic, along with a graduate student with a special focus in archives. The team’s ongoing efforts are organized around the encouragement of a living, digital archive of Weeksville community members’ stories: an organic entity that is forward thinking while looking to the past and engaging the present.

The project’s aim is to establish an ongoing, accessible, public resource that can be used by Pratt students, Weeksville community members, and others to galvanize community networks, build community strength, and subsequently stimulate political will and Black empowerment.

“These are aspirational goals for us that we’re setting at the onset based on studying other archives and how they work in communities,” says Hogrefe. “We’re particularly interested in critical ethnography, which is an understanding of the positionality of the ethnographer and the role of the participant in the co-creation of the archive. Scott worked in New Orleans and I’ve done work in Oakland and Berkeley before in similar settings, and we know, from looking at them historically, the benefits of storytelling, oral history, and critical ethnography.”

Ruff and Hogrefe’s initial collaboration with Weeksville began while they were doing research for their book In Search of African American Space: Redressing Racism (Lars Müller, 2020). Their conversations with the Weeksville Heritage Center evolved into a shared interest in opening up Weeksville’s existing archive to the public and finding ways to activate it. “We saw an opportunity there to say, as architects, part of what we do is activate space as power relations. It’s part of our process. It is not just designing buildings and putting them up,” says Ruff.

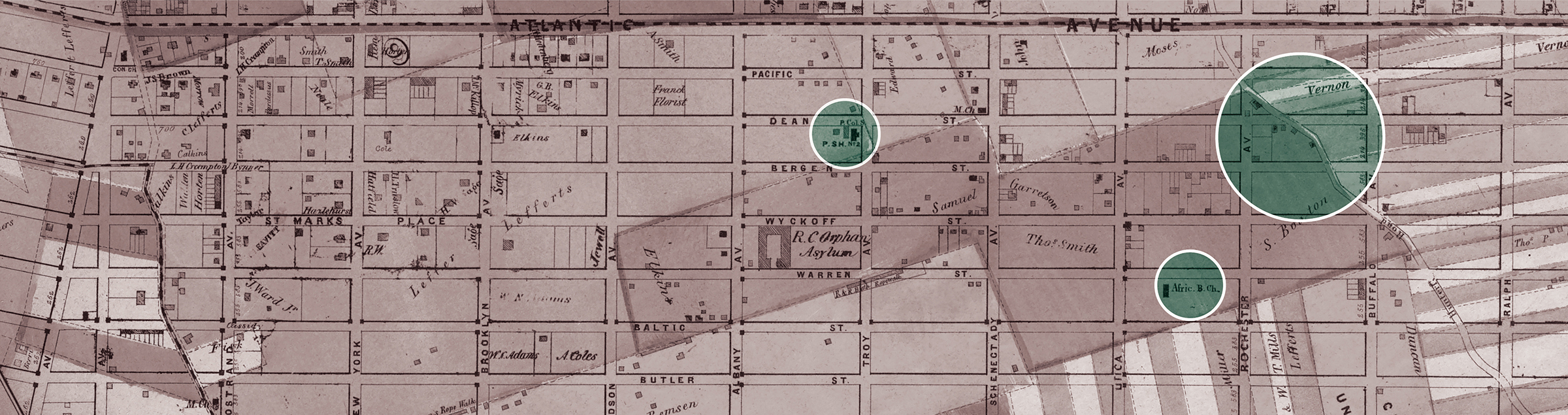

For the Pratt Weeksville Archive, Pratt students participated in that process from its foundational stages. Fifth-year architecture students Joseph Shiveley and Jared Rice, a member of Pratt’s chapter of the National Organization of Minority Architecture Students, prepared by reviewing historical maps of the area. “One of our interests from the beginning was how Weeksville went from being one of the biggest self-sustaining Black communities in the country to one that had been very much erased from maps. When we look at the 1950s, you don’t even see Weeksville on the map,” Rice says, noting that a variety of factors contributed to its erasure over time, under the pressures of urbanization. “We used maps and [looked at] spaces to try to understand how that happened, how it transitioned, so that it could inform the conversations we would have later.”

Sadie Hope-Gund, a graduate student in library and information science, undertook another preparatory process, which Ruff describes as anthropological detective work. Her work resulted in an in-depth annotated bibliography covering the history of the neighborhood, the history of New York City Housing Authority’s presence in the area—public housing that replaced several bulldozed original Weeksville blocks—and radical oral history practices.

Hope-Gund also led conversations to help the team think through the technical aspects of the archives setup. “The archive as a concept is very interesting, but people don’t know much about the nitty gritty,” she says, remarking that part of her work was laying out options for a digital archive. “What are the actual steps to uploading this to a website, what is it going to be hosted on, how is it going to be organized?”

The framing of the project also presented an opportunity to engage with questions around the impact of community-based research work. “What does it mean for an architect to do ethnography in a way that contributes to the community, rather than just drawing data from the community to design a project, which is often how architectural research is done,” says Hogrefe.

Presence is a significant part of laying the groundwork for that kind of reciprocal relationship. While the pandemic may have presented its share of delays and setbacks, the Pratt team made the most of the opportunities they had, such as a street fair outside Bethel Tabernacle African Methodist Episcopal Church, a community partner on the oral history project, last summer. “The one time we were all able to meet in person at a church event, it was really good for us to physically be there and show that we cared and were doing this project about the neighborhood,” Hope-Gund reflects. “That was definitely impactful, thinking about Pratt’s position as an institution in Brooklyn and what it means to really reach out to people and be a part of different communities in Brooklyn.”

At the in-person event last summer, Hope-Gund worked with Obden Mondésir, Weeksville Heritage Center’s oral history manager at the time, to collect the testimonies of Bethel Tabernacle members Faye Robinson and Kay Robbins, who have both attended for approximately 50 years alongside generations of family. In their oral history sessions, both women celebrated the people and the family-oriented, friendly, and passionate nature of the church community. These kinds of anecdotes and impressions form the collective memory that surrounds the story of Weeksville.

Ronald Johnson, the church’s historian, says that you can’t talk about Weeksville without talking about Bethel Tabernacle. The church, established in 1847, was one of the institutions that anchored the community in its early days and remains a vibrant center of activity. Johnson was introduced to Ruff and Hogrefe when he reached out to Weeksville about their archive as he was doing historical research on Bethel Tabernacle, which has an extensive physical archive of its own. This forged a connection he describes as essential. “I believe that it’s a necessity for neighborhood institutions such as Weeksville Heritage Center, our church, even Berean Baptist Church, which is across the street from Weeksville [Heritage Center], and Pratt to band together and collaborate, because we share commonalities in our missions that would be helpful to one another. What I hope for is a further banding together of the institutions,” says Johnson.

Vanessa Smith, a Bethel Tabernacle member with deep roots in the neighborhood, says her hope is that the community will get to know the legacy of Weeksville. “People live there but they really don’t know how historical Weeksville is or the history of the area,” she says.

For Raymond Codrington, Weeksville Heritage Center’s president and CEO, the Pratt Weeksville Archive is significant to bridging that divide. “I think Pratt’s work plays an extremely important role in amplifying the history of Weeksville in ways that draw attention to how race, resistance, and community building intersect with neighborhood change,” Codrington remarks.

To date, the project team from Pratt has completed six oral histories, and more are planned with the participation of Bethel Tabernacle, local community garden members, and new Pratt team members Caleb Joshua (CJ) Spring and Cierra Francillon, both fifth-year architecture students.

To add further longevity to the work, the Pratt team has created a framework for using cell phones to engage and empower community members to interview one another, establishing an armature to help sustain the voice of the community over the long term. This is also a means of ensuring that authorship of the narrative of this space is in the hands of its residents.

“Settler colonialism is still alive today. The term postcolonial is a misnomer. I think the decolonizing movement is more assertive in looking at how the structures of colonialism can be taken apart. That’s been part of our project,” says Hogrefe. “We feel that we’ve started something that will ripple throughout the community. It will support communities that care about themselves and are able to go to the community board and participate politically, especially as we begin to work with youth who have the energy to do that.”

That youth engagement is happening in initiatives like Co-Designing Brooklyn’s Hidden Heritage, which Ruff helped develop, connecting students at Weeksville-adjacent Medgar Evers High School with undergraduate and graduate architecture students at Pratt. For young Black residents of Brooklyn, Ruff says, he wants them to understand history so they can imagine a future. “This is your place that was purchased for you. That was a sanctuary for you. And you are the legacy and the future of Weeksville and this idealized place,” he says. “How do we continue that or honor that? If we can recover it and begin the process of continuing to build the place, then there will be more political strength for the people of Weeksville as they come together under an idea of place and of history, and of legacy. That’s really the empowering aspect of it.”

For anyone visiting the Weeksville Heritage Center—designed by Caples Jefferson Architects, where Pratt alumnus Everardo Jefferson, BID ’68, is a principal—there is a tactile quality to the building’s facade. A sense of layered texture generated through a juxtaposition of materials—wood, cool blue and gray stones, glass that reflects the sky, and elegant brass gates. Its low height does not impose a sense of grandiosity and its interior spaces are warm and reference African forms. Outside a grass lawn and interpretative landscape, designed by Elizabeth Kennedy, connect the new contemporary structure to the rediscovered 19th-century homes known as the Historic Hunterfly Road Houses, named for the Lenape trail they were built along. In quiet moments, a powerful meditative sense of sacred Black and Indigenous space is undeniable.

The land and the built environment speak to a Black continuum that runs from the utopian goals of Weeksville’s founder and residents in the 19th century through to the aims of the Heritage Center to bring the story of Weeksville into the consciousness of Brooklyn today and into the future. Where Pratt entered that story in the 1970s and has continued to weave through in the work of alumni and faculty engaging with the space, through the Pratt Weeksville Archive, there is now a chance to contribute to the instrumentality of Weeksville’s transhistorical presence through diverse, intergenerational collaborative practices.

For Ruff, the Heritage Center—like the archive surrounding the oral history project—embodies an ancestral presence, simultaneously futuristic, contemporary, and ancient. “It has aspects of all of those things within it,” he says, “and so it becomes a very powerful space for us to center on and for us to galvanize the community to say new things can happen here—in the name of Weeksville.”