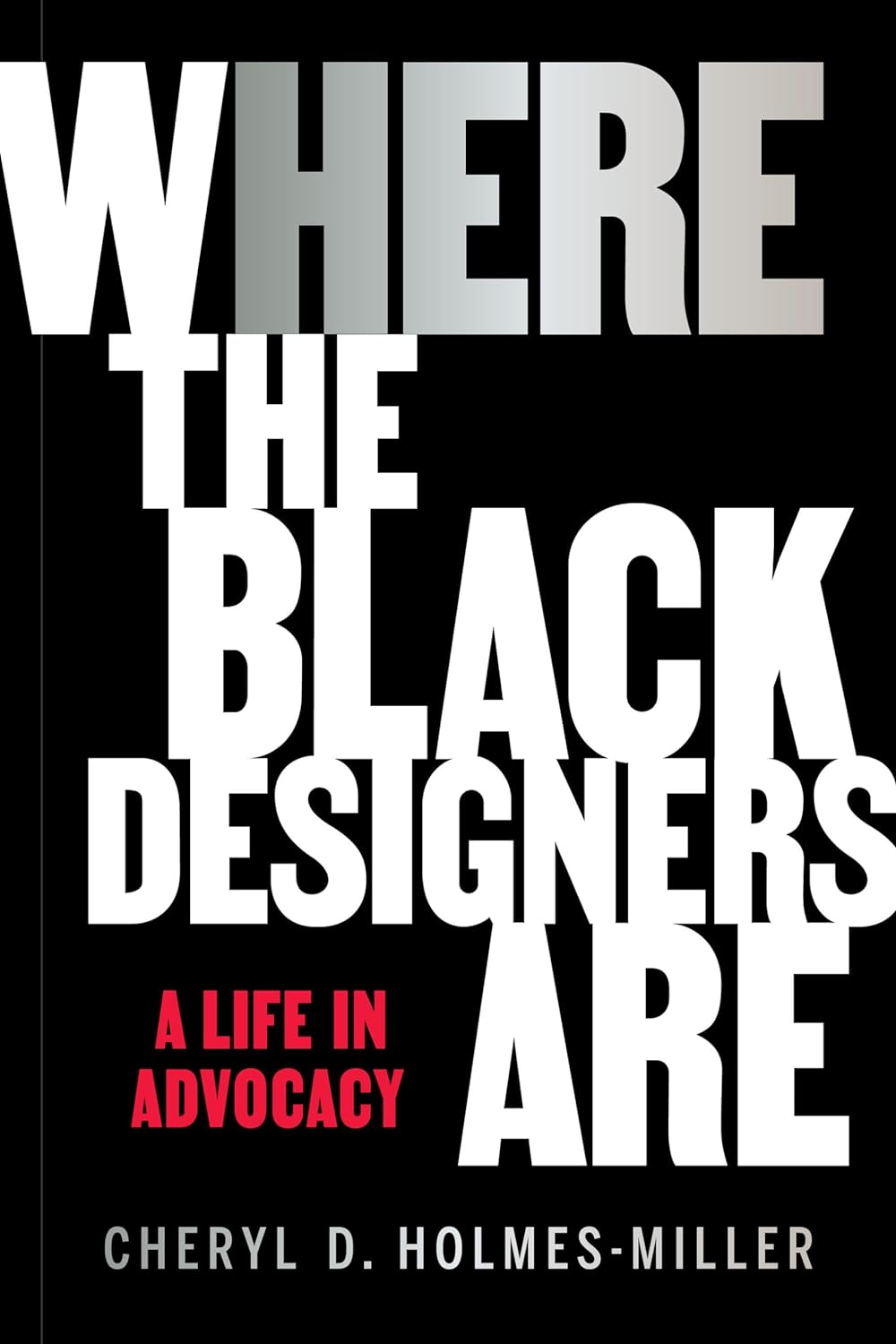

A question has confronted graphic designer Cheryl D. Holmes-Miller since the start of her career: “Where are the Black designers?” She explored it as a writer, first in the form of a trailblazing master’s thesis for Pratt Institute, then in a viral article for Print magazine, “Black Designers: Missing in Action,” and addressed it firsthand as the leader of her design firm, Cheryl D. Miller Design. In the decades since that first publication, the question has been a prominent thread through her many articles, interviews, and lectures nationwide.

In the latest chapter of a lifetime of advocacy, Miller compiled her observations and thinking into a new book, HERE: Where the Black Designers Are, published by Princeton Architectural Press in October 2024. Calling the work a “treatise and documentation of a historical graphic design movement in search of a missing professional,” she aims to answer that seminal question—“Where are the Black designers?”—as she takes readers through a timeline of Black graphic design. The book blends Miller’s research with her personal experience, along with visuals ranging from 18th-century woodcuts to contemporary posters, branding, and editorial design, underscoring the message: Black designers have been here all along.

Here’s a look inside the book, highlighting pivotal moments in design history and Miller’s story:

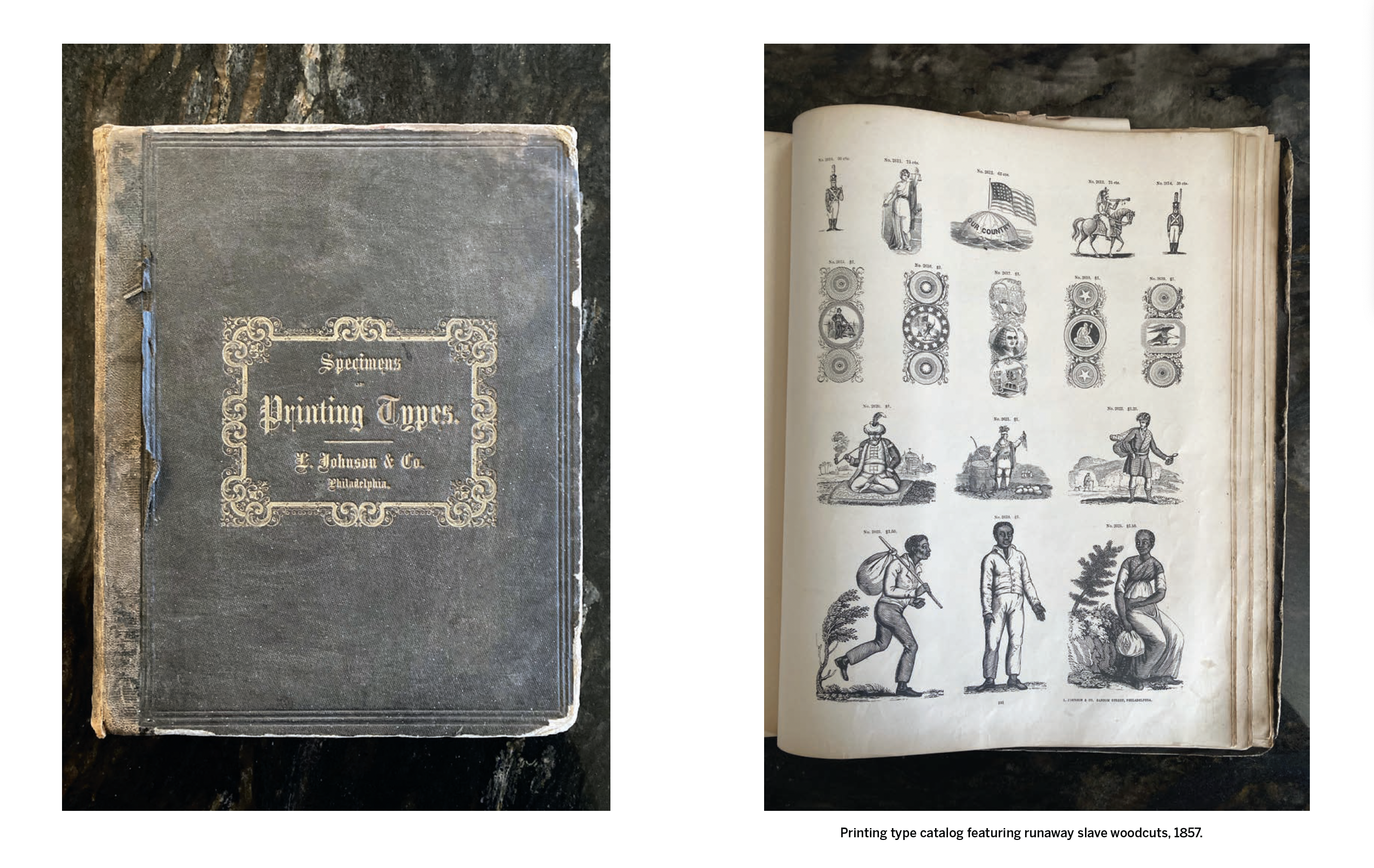

Early American Woodcuts

In her research, Miller found that “the first Black graphic designers” in American history may have been enslaved printers, engravers, and woodcutters applying West African illustration aesthetics to advertisements seeking runaways. “The Slave Artisan is our first Black graphic designer, and because he was enslaved, he doesn’t appear in our graphic design history,” Miller writes. “Many of us boldly and collectively keep the West African design heritage alive; it is our aesthetic . . . To know your history is to know your future!”

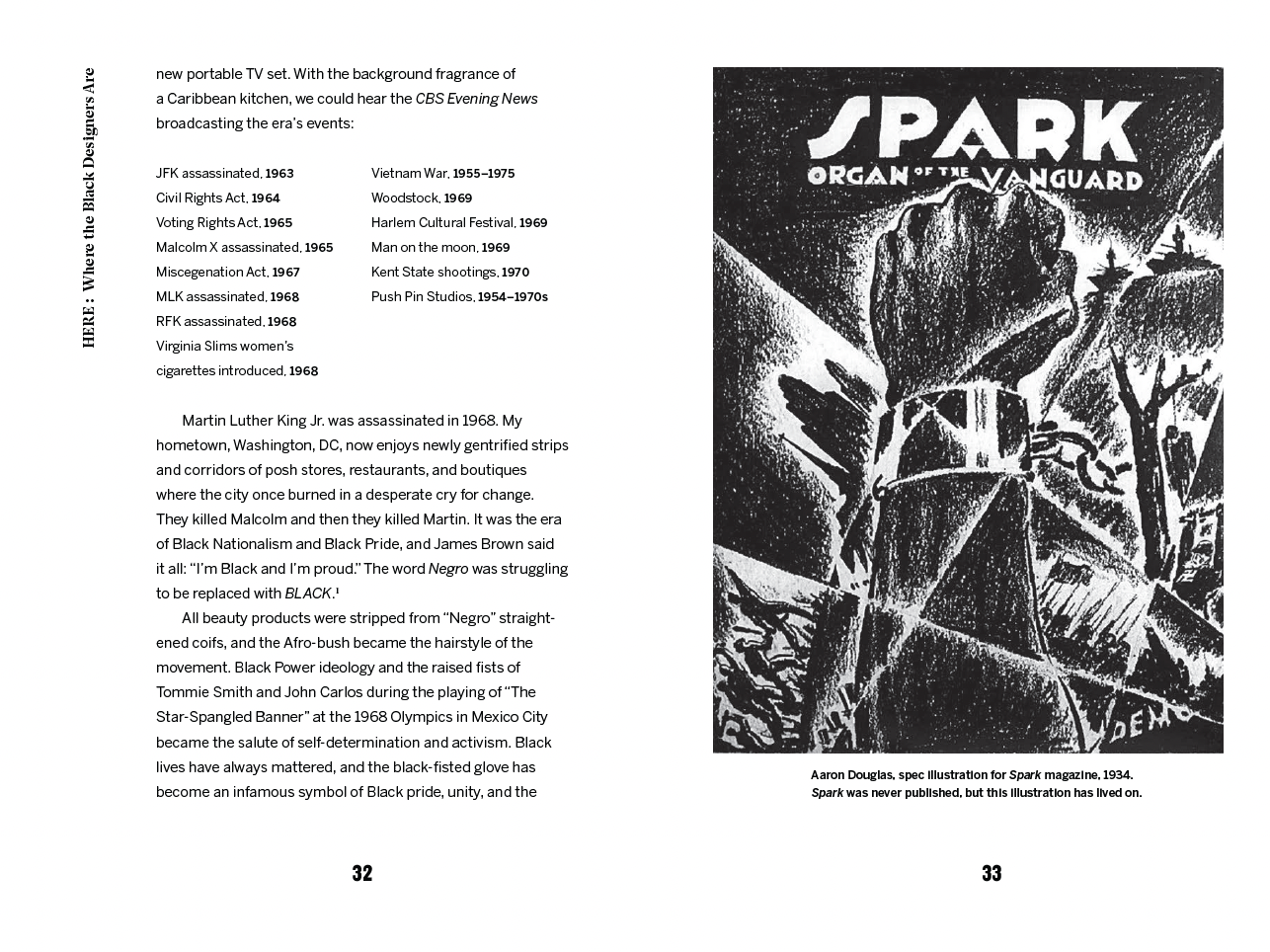

The Civil Rights Era

Born into the restrictive culture of the Jim Crow era, Miller recalls that the “pre–Civil Rights era, the Civil Rights era, and the post–Civil Rights era are the seasons of my coming-of-age story and my journey of art and design. I lived through extremely important American sociopolitical events and pop-cultural shifts.” Miller took great influence from this period, when the image of a raised Black fist (which she notes was first shown in an “unpublished Spark magazine cover from 1934” by Aaron Douglas) came to symbolize “Black pride, unity, and the solidarity of the disenfranchised, oppressed, overlooked, and forgotten.”

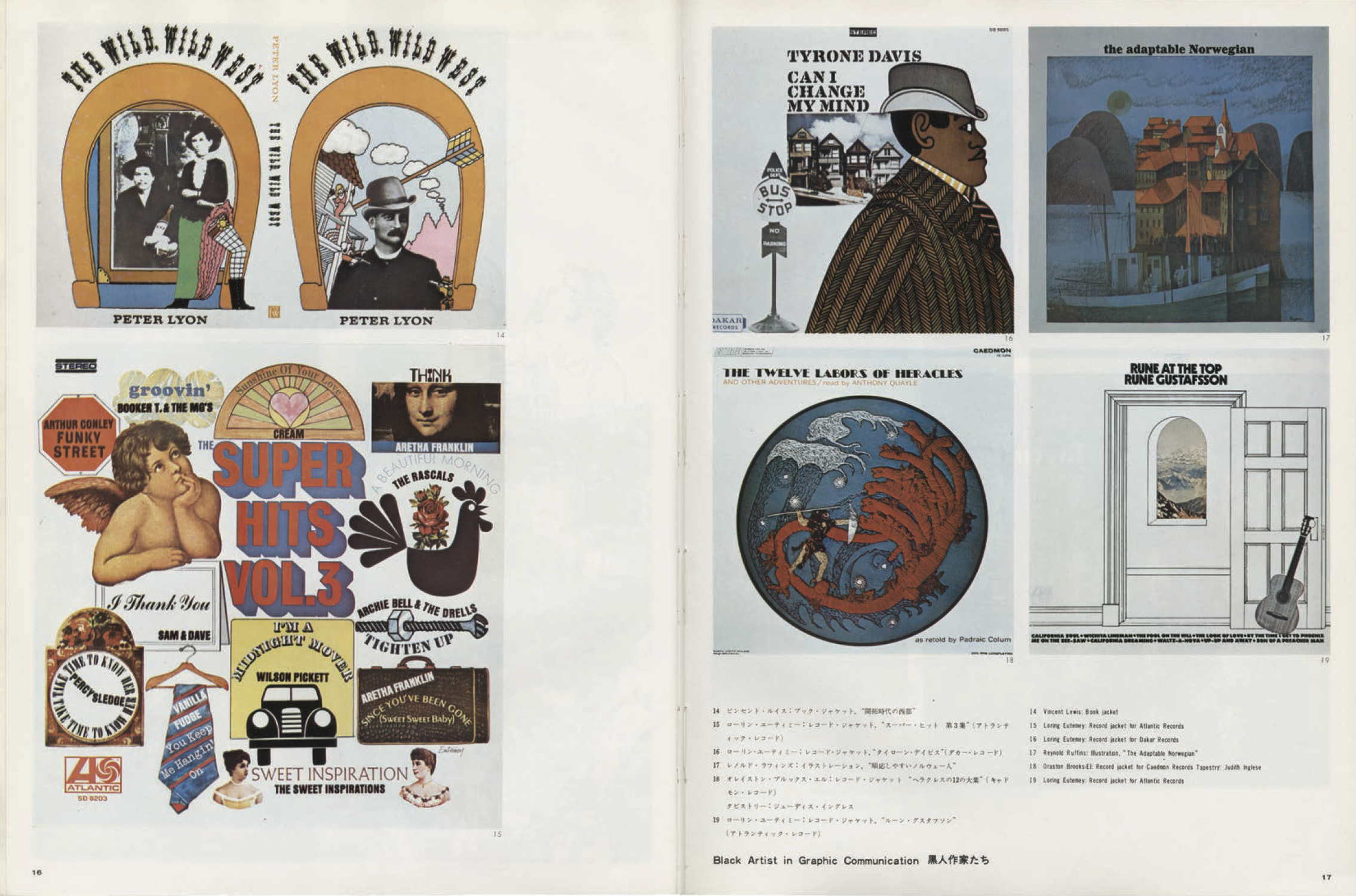

Black Artist in Graphic Communication Exhibition

For Miller, the 1970 Black Artist in Graphic Communication exhibition encapsulated “the story of the Civil Rights–era Black graphic design advocacy.” Graphic designer and educator Dorothy E. Hayes initiated the exhibition, which showcased 49 overlooked Black graphic designers in the Composing Room’s Gallery 303 in New York City. In Miller’s words, “Hayes wanted to boldly exhibit to the advertising and publishing industries and businesses that a vast reservoir of talent existed . . . was successful, and had a voice. The exhibit was her way of shining a spotlight on a dimly lit stage.”

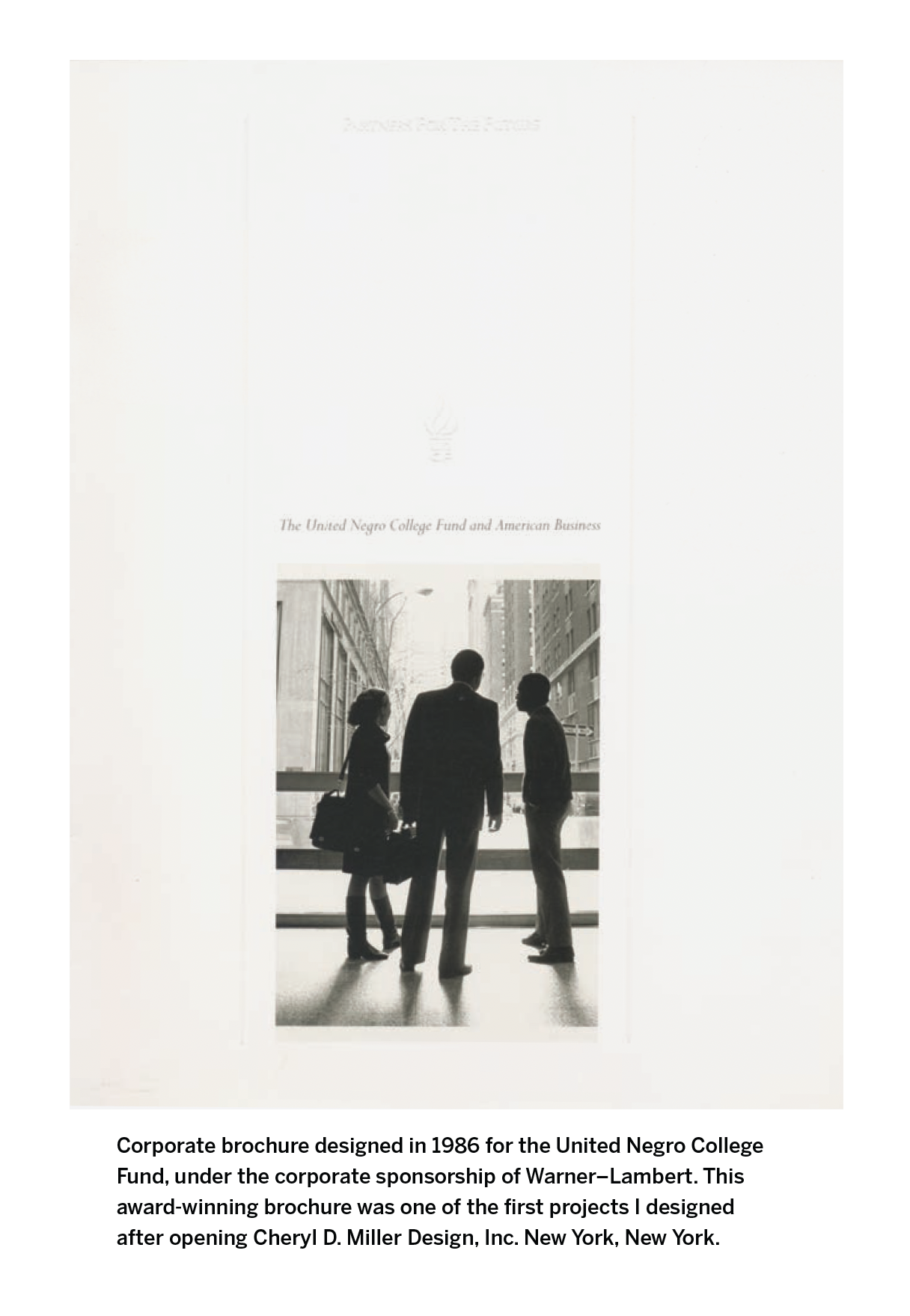

Cheryl D. Miller Design

The book also weaves in Miller’s own creative work, which by the 1980s was pushing the needle on Black design visibility. In the words of educator and academic leader Crystal Williams, who wrote the book’s foreword, Holmes-Miller “is among a rare group of artists whose own creative accomplishments are equal to their social impact and activism . . . [her] work for Chase Bank, McDonald’s, and Philip Morris proved that Black firms and designers were more than qualified to create quality iconography for the Fortune 500’s broad audiences and could innovate successfully.”

Related Reading

Perspective: With Cheryl D. Miller, MS Communications Design ’85

35 years since its publication, a landmark article and the Pratt thesis behind it still resonate.

Perspective: With Farah Kafei and Valentina Vergara, both BFA Communications Design ’18

Farah Kafei and Valentina Vergara advocate for more women in positions of influence in design—as educators and mentors, and in the history books.