Two decades ago, the influential design text Cradle to Cradle asked how we as a species could leave a footprint “to delight in, not lament,” looking to nature for cues for how to create more beneficial products and systems. In the Graduate Communications Design studio Sustainability and Design, taught by professor Jean Brennan, students are considering the effect of design with a holistic view of the process, from materials use, to distribution systems, to social and economic implications, as they develop solutions that renew, regenerate, and inspire. Last spring, students in the course began with site research around Pratt’s Brooklyn campus to record material waste; grew materials from organic sources like coffee grounds, crustacean shells, and banana peels; and worked in teams to come up with innovative, ethically considered package-design proposals.

For their project, Pits and Peels, students Allie McElwee and Mariana Romero-Carrillo, both MS Packaging, Identities, and Systems Design ’23, examined the potential of organic waste to generate new biomaterials and methodically documented their exploration, taking an approach that united science, art, and social impact. “Allie and Mariana took a hyper-local and intimate approach to the class prompt,” says Brennan. “Pits and Peels responds to a need in their immediate neighborhood where there is no city composting program and many of the residents do not have access to a backyard to initiate food-waste recycling on their own. Their project responds to this need with wonder and joy by thinking about the aesthetics and form potential of biomaterials made from a myriad of kitchen scraps. And this is where they really shone—they tirelessly produced and documented so many beautiful samples. While the outcomes speak to their aesthetic vision, they took a very scientific approach by limiting the binding ingredient so they could compare and contrast different biomaterials and their potential. This prompted them to develop a metrics system to evaluate the tensile strength, flexibility, aesthetics, texture, and scent of the various recipes.”

Romero-Carrillo and McElwee discussed their final project with Prattfolio.

What was it about food waste that sparked you both to explore its potential? How did you set parameters for your exploration—for example, it seems like part of your objective was to find beauty in the materials?

Mariana Romero-Carrillo: We started our project by collecting coffee grounds, as we noticed the significant amount of them that go to waste with only one serving. After conducting research, we came across projects like bottles and paper made out of this material. This led us to take a closer look at our kitchen garbage and think “what else do we throw away on a daily basis, and what can come of it?”

Allie and I both live by ourselves in studio apartments, which could suggest that less trash is generated based on the amount of people in the room. Yet, our bins are always filled with food scraps like fruit and vegetable pits and peels, delivery containers and wrappers.

We started taking a closer look at these materials and thinking about possible applications in packaging design. As Allie cleverly said, “pits and peels are nature’s packaging, so why not mimic and give back?”

I would agree that part of our project was finding the beauty in the materials. I like to think that packaging doesn’t need to be boring and this is what conducted our research and experimentation. I studied marketing in my undergrad and of course I think of the consumer first and how they form their opinions. Interactions with the product matter and first impressions make it or break it. Questions like, how does it feel, is it rough or soft to touch? How does it smell? Does it bend? Does it stick? Is it ugly brown or pretty purple? Pits and Peels offers that intriguing aspect and initiates conversations.

I think packaging is fun when you can interact with it.

Allie McElwee: While looking at our own household waste as well as the waste in our Brooklyn neighborhoods, we were struck by the volume we each would generate on a weekly basis. Given the lack of accessibility of a composting program in our areas, we began to consider other options for our waste. As we are not scientists or engineers with access to commercial production facilities, making aesthetically pleasing bioart was a tangible platform for us to create while also considering the viability of the materials in the context of packaging. It was fitting for the volume of waste and our own production capabilities.

We choose to make aesthetics a priority as this has implications for packaging but also would be satisfying in the creation process. We both like to eat our fruits and veggies, which allowed us to work with a range of colors.

When you did the community study, were there any trends you were surprised to find? What waste materials initially felt like they had the most potential?

MRC: The materials that initially felt like they had more potential were those that originally had interesting texture and smell. For example, lemons and limes, and avocado peels. Nonetheless, our favorite sample was made out of rice water, because the starch helps create a more sturdy plastic feel.

Using water residue could be considered “a trend” as you describe it. When we think of food scraps or waste, we don’t think of the juices or coloring that can be extracted. For instance, we boiled onion skin and used the rich orange color to dye some samples.

AM: We both began experimenting with coffee grounds after noticing the high number of coffee shops in our neighborhoods and the Pratt area. This seemed like a good jumping off point in terms of sourcing waste if we were to produce biomaterials at a higher volume or larger pieces of art. It also allowed us to consider working with community businesses if we were to land on a viable biomaterial to produce with at a larger scale in the future.

As we continued to experiment and really dive into bioart creation, we found ourselves drawn to the more compelling colorful waste as well as the rice water or less fibrous agar concoctions. These were more malleable or felt like they had more legs for packaging potential.

What were the most important specifications or qualities you were looking for in a material that could be used for packaging?

MRC: We were focusing on texture, smell, color, elasticity, transparency. There were some [materials] that had a terrible smell, like pumpkin seeds, but lemon peel had a beautiful color and scent. Examples like these highlight the opportunity to use pits and peels as materials to help us naturally elevate our products.

Interaction is key and having interesting color and texture adds to the experience.

AM: Exactly! Definitely considered those elements while also considering what materials would interact well with our material creations and what those limitations would be. This was really exploratory as we were not considering packaging a specific product while we were creating. After the fact, we would consider what material could work with what and landed on the sandwich wrapper prototype.

Thinking of the final review, what kind of feedback did you receive that helped you think about next steps your project could take, if you chose to work on it further?

MRC: The kind of feedback that I got was mostly on how we were presenting the samples. Each is so unique in color, that having them displayed with a dark background created contrast.

There was also a lot of encouragement to push the product forward and move beyond “experimental stage.” For next steps, we should consider having a more solid structure of a plastic and track how it biodegrades or decomposes.

AM: Yes, I agree with Mariana that presenting the visuals in a way to make them pop was excellent feedback in terms of accomplishing the primary goal of the project, or at least its initial phase.

Additionally, the feedback to include all of our metrics as well as being more detailed with a few highlighted materials helped really articulate the volume of experiments we did as well as provide some context as to how we determined what to prototype . . . that we were not being arbitrary in these choices.

The next phase would likely involve further experiments with 5 to 10 of our more successful recipes, including evaluating their lifespan or seeing if they had one, as Mariana mentioned.

I think evaluating the material’s interactions with a couple control products would be a must as well.

What has this project inspired you to consider in terms of your own design practice? What’s next for you both?

MRC: The project opened my mind to thinking beyond conventional cardboard, plastic, and glass. As designers and consumers, it’s our responsibility to create solutions, not generate problems.

For my next projects, I’ll always consider having the biodegradable option in terms of materiality. I think of pits and peels like an extra added value to a package because it gives us something to talk about, and isn’t this what brands want?

AM: Pits and Peels really expanded my knowledge of biomaterials that I can create on a small scale but more importantly (at least in the short term) the ones that exist at an industrial or small-scale level, like Notpla. Jean Brennan also did a great job of introducing our class to the resources that exist at Pratt, like the Material Lab and the Sustainability Center. This was extraordinarily helpful and something I’ll continue to tap into with any future prototyping I do at Pratt and in the future.

More student work from Sustainability and Design

Claire Chen, Sveva Michahelles, and Eunice Su, all MS Packaging, Identities, and Systems Design ’22

Bathroom Accessories from Seashells

Claire Chen, Sveva Michahelles, and Eunice Su explored plastic-free packaging for travelers, drawing inspiration from popular getaway locations—beaches and oceans, sites that also bear the burden of global plastic waste.

They looked at the potential of shells from mussels and clams to form material that could be used in two product lines: a bath accessories set for hotels, spas, and other tourist destinations, and a set of refillable travel bottles for toiletries. (The project was also highlighted among the Material Lab Prize 2022 nominees.)

Anu Manohar and Prachi Sheth, both MS Packaging, Identities, and Systems Design ’23

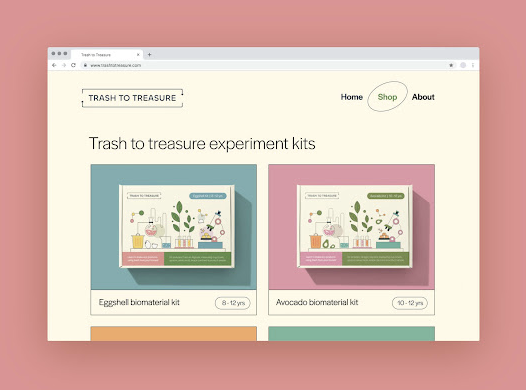

Trash to Treasure: A Biomaterial Kit for Children

Anu Manohar and Prachi Sheth devised an activity-kit concept for children to help them learn about creative reuse of household waste and how biomaterials connect to care for the earth.

Shifting the lens from plastic waste to food waste, customizable kits would guide children in creating biomaterials with sources like avocado peels, coffee grounds, and eggshells, that can then be used to make products.