Living in cities offers tremendous rewards—proximity to culture and community, knowledge sharing and diversity, and density, posed as a solution to housing scarcity—but at what cost to the outskirts responsible for helping an urban center run? Meanwhile, densification outside the city may be a key to addressing the urgent need for housing, but development can have disastrous implications for the environment, climate, and natural resources.

How can architecture lay the groundwork—literally, from the level of vital infrastructure—for more livable, flourishing cities, suburbs, and beyond? In the Pratt Institute undergraduate architecture studio Energy Collectives: Toward a Resilient Workforce Housing Model, students set out to investigate this question, generating new models for a self-sustaining housing ecosystem.

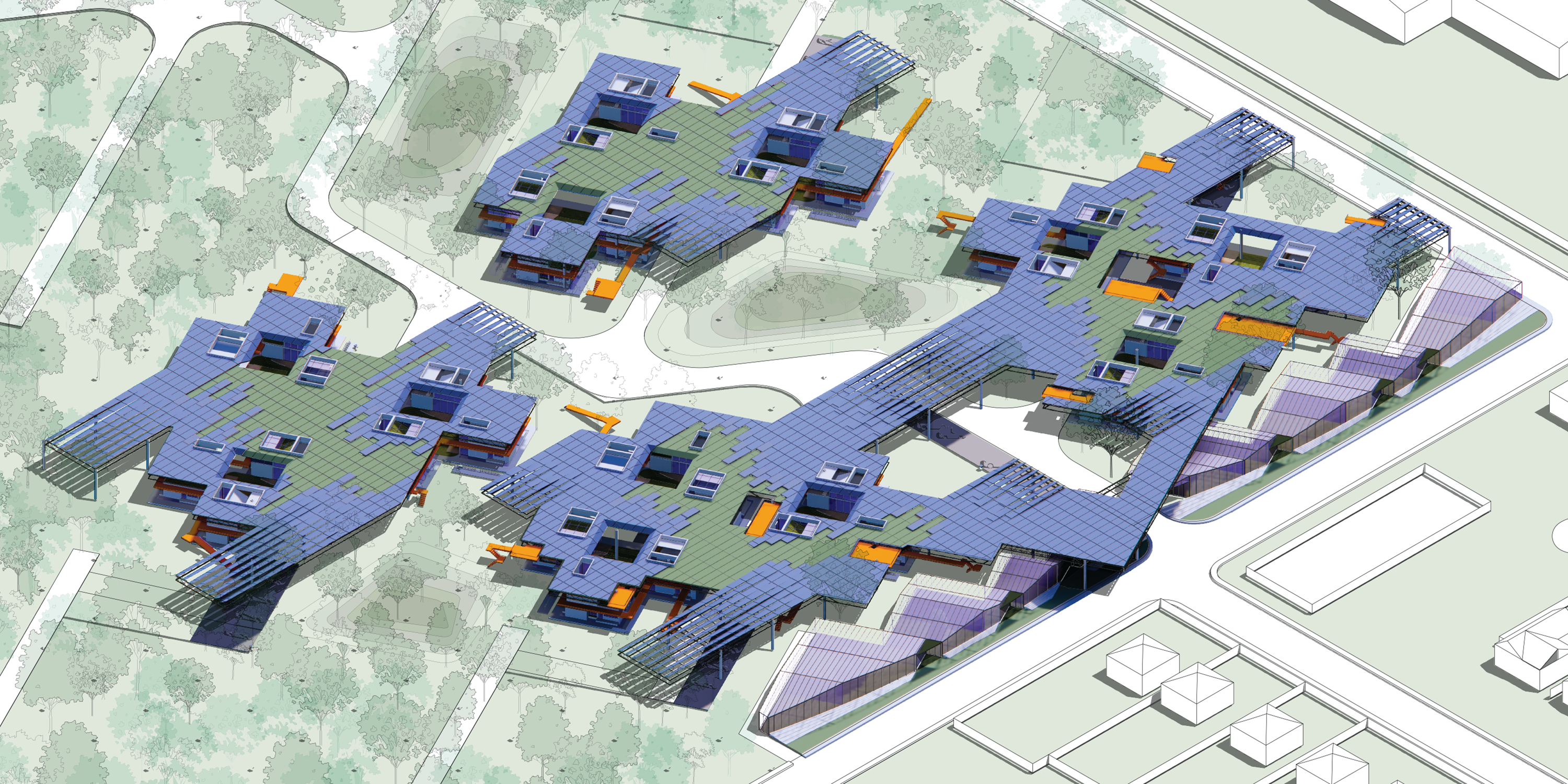

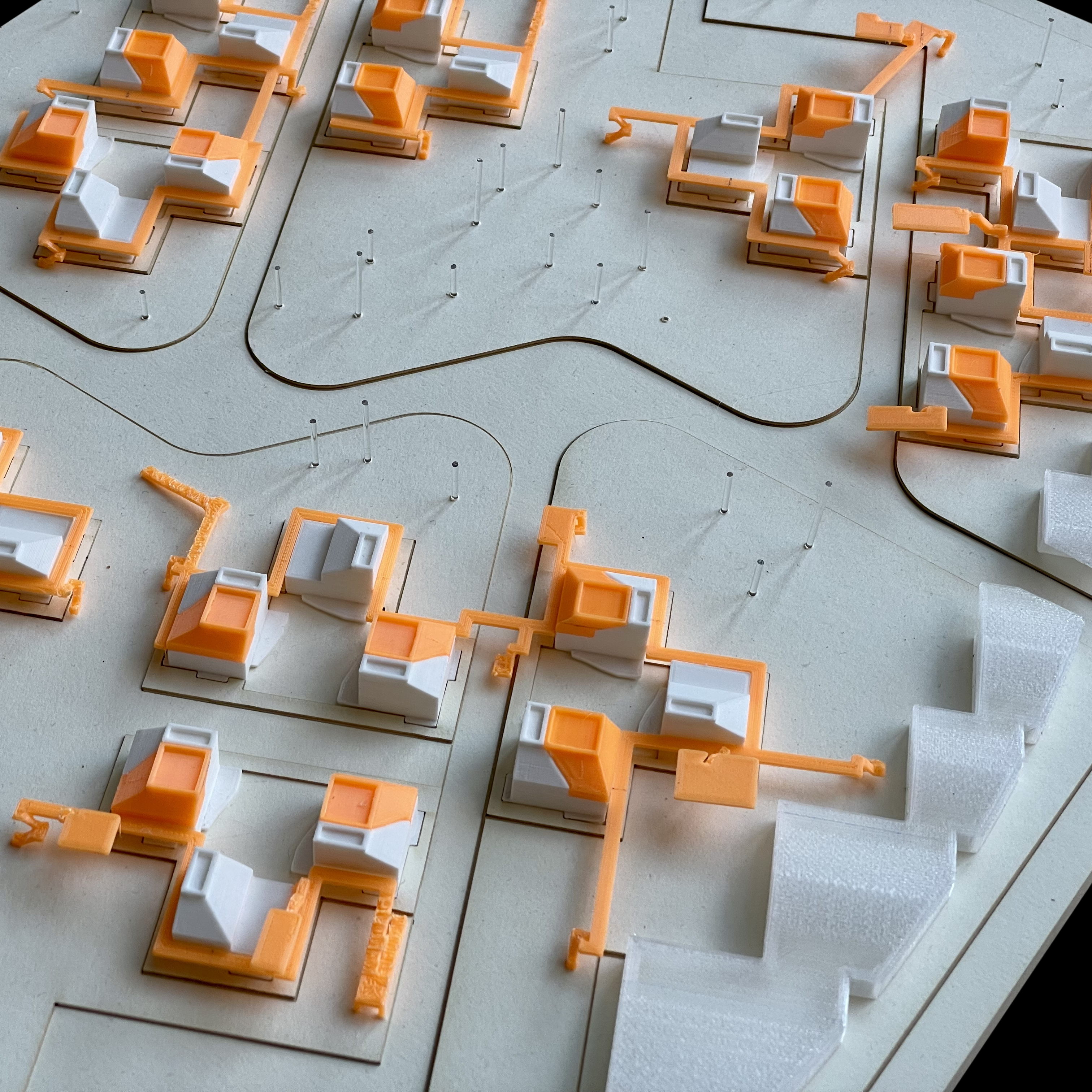

Focused on a site on the periphery of Houston, Texas, the class, held in the fall of 2022, challenged students to imagine a live/work community that would share resources such as food, water, and energy, and to design infrastructures for production and conservation of these resources.

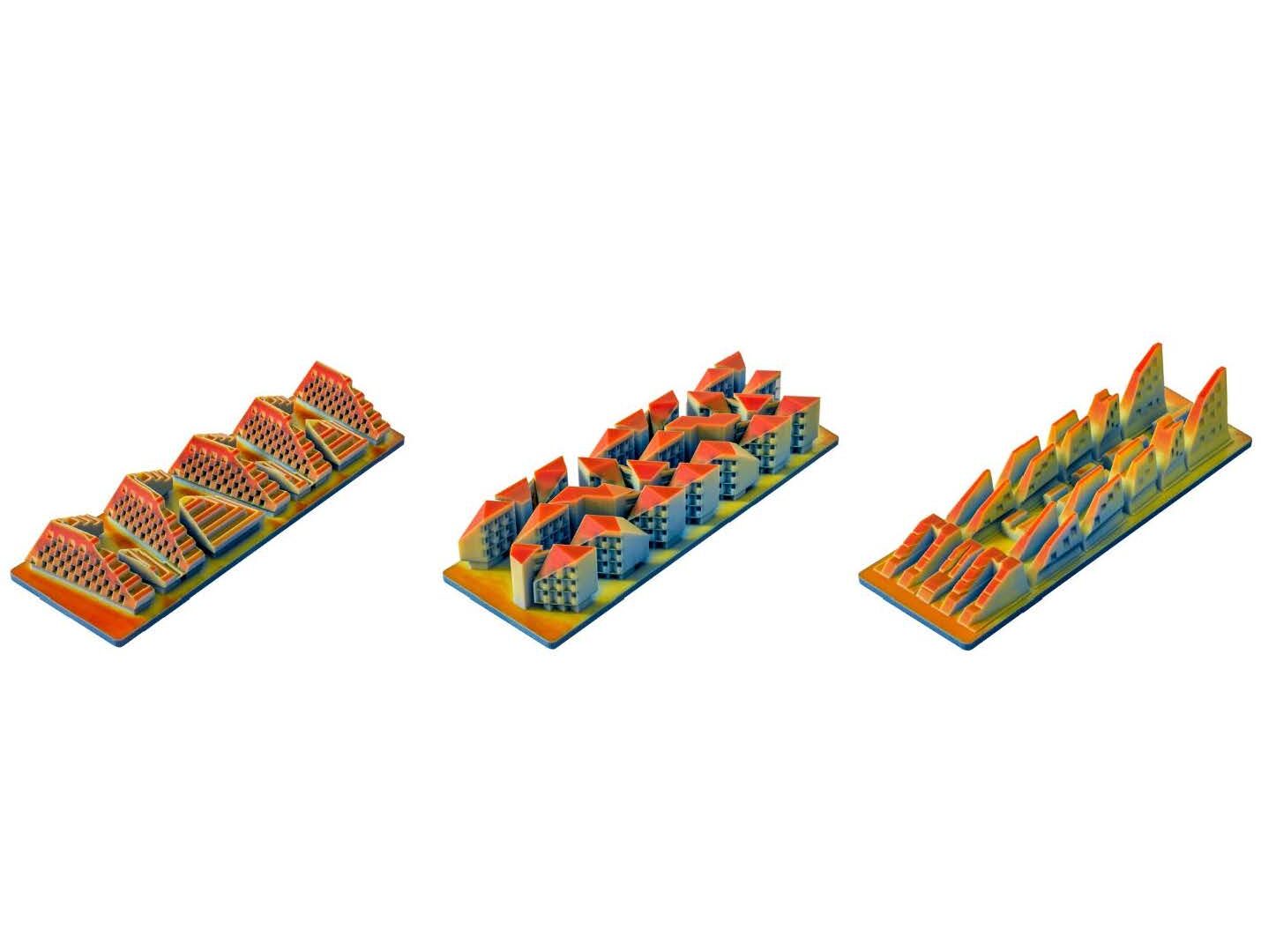

For Pratt Undergraduate Architecture Professor Lawrence Blough and Simone Giostra, who designed and taught the class, Energy Collectives is an extension of a series of studios they ran, with support from the Institute of Design and Construction (IDC) Foundation, on form and energy performance in residential buildings. In those studios, they researched solar design principles and formal models that, together, could produce onsite energy and more energy-efficient buildings, using New York City, with its layers of opportunity for addressing housing challenges, as the site of investigation.

“It’s on our doorstep in Brooklyn,’’ Blough says. “We see the crises and they are unavoidable. We have to develop creative solutions for issues such as the working class ‘missing middle’ who are being forced out of the city due to high costs of housing, or the need to address changing lifestyles such as remote working, or designing new proposals for climate resiliency focused on locally produced renewable energy. We live in a dense city, and that’s our laboratory.”

Energy Collectives has widened the scope of research to the suburbs of Houston, a region like Atlanta or Austin—two other cities Blough and Giostra researched in designing the studio—that is “grappling with smart growth strategies, pressing needs for increasing density with affordable housing, along with sustainable land use and resource management,” as they say in the course proposal.

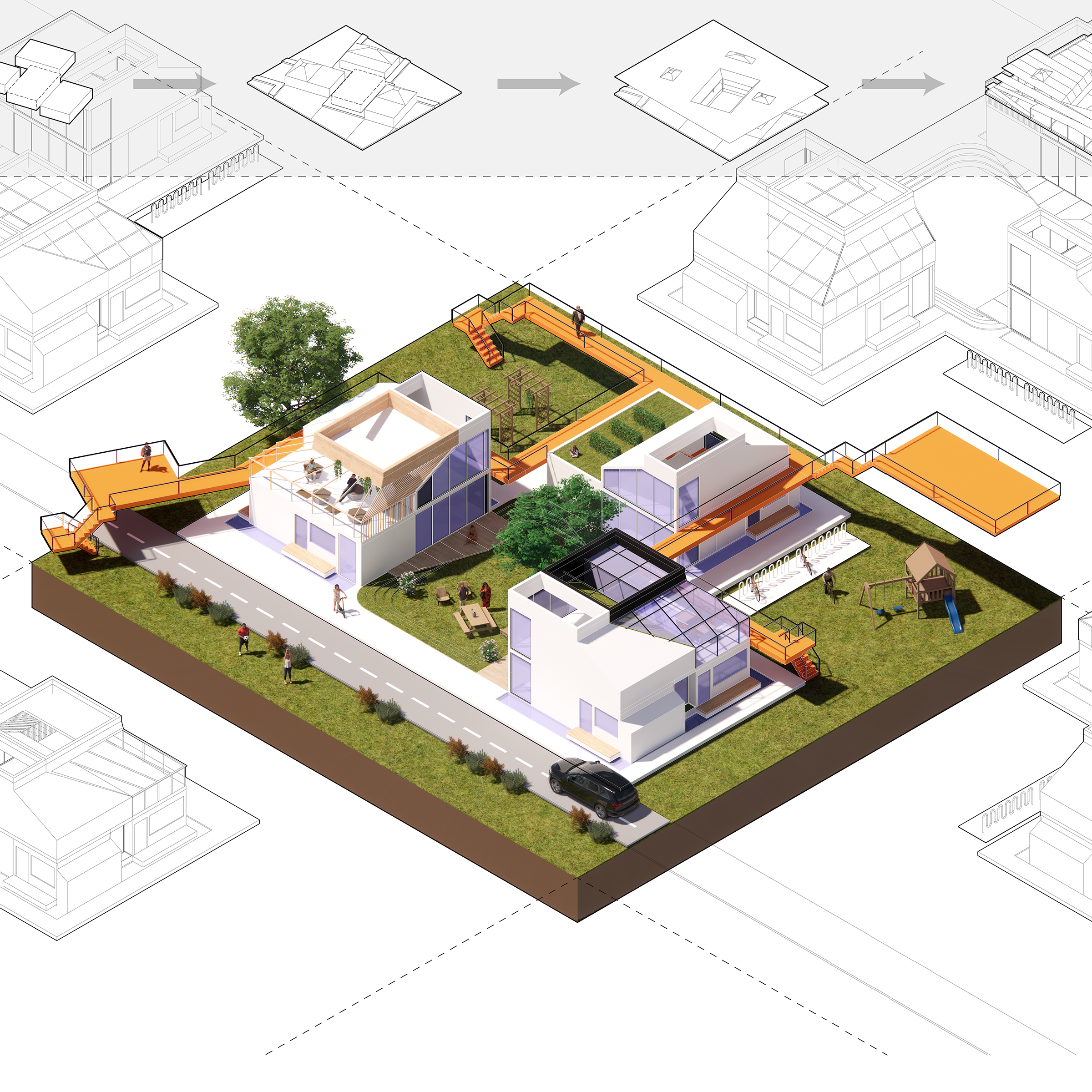

The focus beyond a dense, urban setting presented some students with a new frame of reference that expanded their thinking of how a collective living model could be applied. “I have worked with co-housing and co-living in a previous studio, but this was within a city fabric, in an apartment building,” says Raphael Baranello, BArch ’25, a student in Energy Collectives last fall. “What is expected in a suburban neighborhood has a different scale of density and modes of privacy than in an apartment building.”

Students began the studio getting familiar with what Blough and Giostra refer to, in their course proposal, as FEW2: “Standing for food, energy, water, and waste, FEW2 was to be the focus of our semester, and each of our projects began with the need to address one of these concerns in a relationship to designing a housing cluster for three families that we later scaled up,” Baranello explains.

Students considered infrastructure around these four focus areas alongside affordability, resource sharing, and the environmental implications of increasing density—a strategy to address housing scarcity. Baranello chose water as his topic, “more specifically, rainwater collection and distribution.” His research examined how, through the effects of climate change, water levels rise, and as development compromises Houston’s wetlands, which can mitigate the effects of excess water, the city’s current defenses against flooding become overburdened.

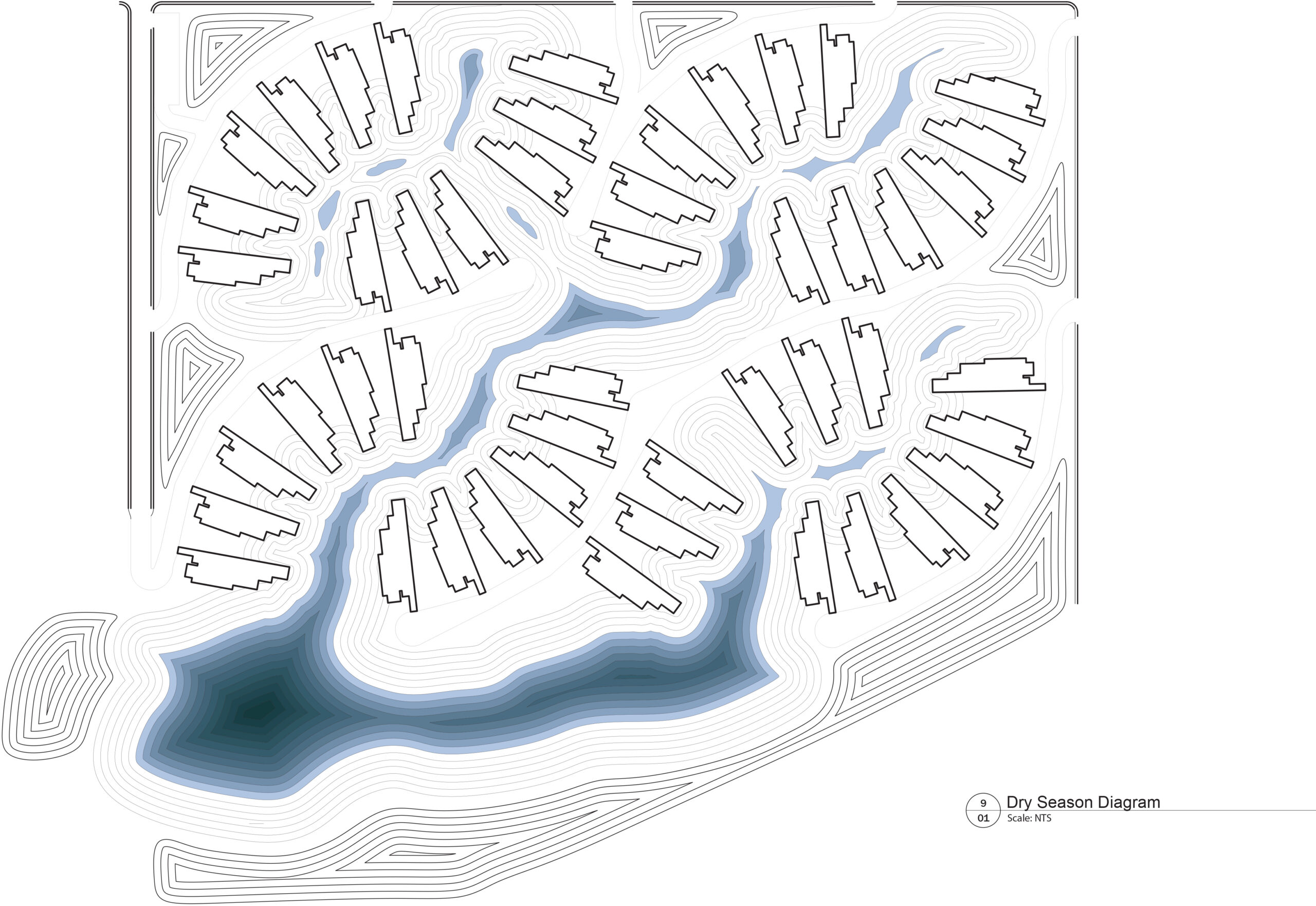

“The result of my research was a series of infrastructural diagrams that outlined rainfall statistics, collection methods for that rainwater, and necessary calculations and quantities for reaching self-sustainability,” Baranello says.

By analyzing and designing for the region’s climate, weather, adjacency to water bodies, and floodplains, Baranello was able to plan out an aggregation of three-family units that spread across a 24-acre vacant lot in northeast Houston. He diagrammed a natural lowland surrounding the houses that would retain rain and floodwater, ensuring a continuous natural wetland throughout the year. In Baranello’s plan, rainwater would be collected and filtered through a UV purification system into a water tank—the primary water source for the surrounding family households with excess water being slowed and absorbed through a system of planted roofs, bioswales, and retention ponds.

Other students researched collective opportunities around changing lifestyles such as working from home and energy sharing. “People are seeking alternatives that better align with their evolving needs, recognizing that traditional housing typologies may no longer meet their requirements,” shares Daniel Hsu, BArch ’23, also a student in last fall’s studio. “Thinking about housing on another scale”—beyond an isolated single-family unit, for example—“has the potential to transform the entire neighborhood.”

The Energy Collectives studio is among several initiatives that Professor Blough has launched across Pratt that bring architecture into conversation with urgent issues in the housing space. In 2020, he organized Domestic Mutations, an exhibition of architectural models exploring collective live/work scenarios surrounding labor, leisure, and post-familial life. Last year, with Professor of Undergraduate Architecture Deborah Gans, he started the Housing Futures Research Lab. This project is part of the IDC Research Accelerator Hub and supported by the IDC Foundation at Pratt’s recently opened Research Yard in the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The lab works with experts across disciplines to develop solutions to issues involving the housing crisis.

“Design is a powerful tool,” Blough says. “What’s the agency of architecture to address the most pressing societal matters such as the housing crisis and the climate emergency? How can we as designers create a new aesthetic towards a public climate consciousness?”

With the Energy Collectives studio, Blough and Giostra have helped students to find that agency in their design work, around contemporary housing issues that demand paradigm-shifting thinking. “Both professors pushed me to be creative and reminded me that the point of the studio is to challenge the existing infrastructure,” Baranello says. Hsu, who since graduating has worked as a freelance architectural, industrial, and graphic designer, says he learned how to “conceptualize a novel way of life” through this studio.

Energy Collectives will run again in the spring of 2024, aiming to dig even deeper into the potential of co-living and sharing resources as a foundation for sustainable urban and suburban growth.

“The norms we know today may not be the norms of the future,” Baranello says. “What if there is a way to design that doesn’t force self-sustainability, but fosters it.”

Related Reading

Pratt Institute on Winning Proposal for Governors Island Climate Center

Pratt is a core partner on the Stony Brook University-led team that will build The Exchange, a world-class climate center on Governors Island.

The next generation of architects learn principles to address climate change from an expert in energy-efficient design at Pratt Institute.