This story highlights five student projects that touched on themes of adaptability and resilience, with excerpts from student and faculty conversations at this past spring’s final, virtual reviews. (Excerpts have been edited and condensed.)

Even before the global pandemic and amplification of social justice actions focused our collective attention on physical and mental health, care of the self and community, and systems that aid or inhibit thriving, Huynh’s students in Nourishment and Social Change were working on industrial design projects that investigated these topics. As life and learning shifted in March of 2020, some students considered alternative dimensions to the central problems they were exploring and modified their projects in the emerging crisis, and others gained momentum as their work took on heightened urgency and relevance.

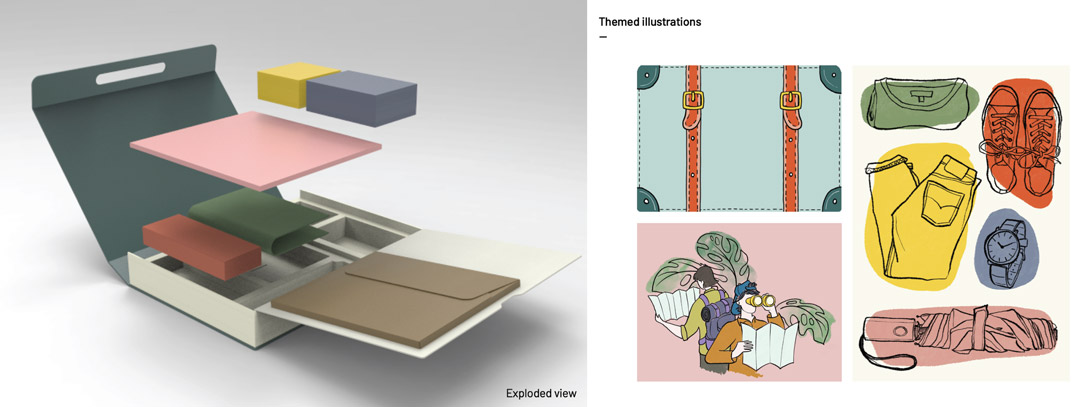

Claire Seonjae Choi, BID ’20: Maeum

Mental Health Discovery Kit

“Suicide is one of the biggest social problems in South Korea,” Claire Seonjae Choi observed. “Its suicide rate is 26.6 deaths per 100,000 persons. Even with the government’s effort, the country still has ranked the highest among OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development] member countries for 15 years.”

Proposing that conservative approaches to mental health at a young age can lead to sometimes catastrophic challenges in managing psychological well-being into adulthood, Choi focused on developing approachable, adaptable educational tools specifically targeted for fifth- and sixth-grade students in South Korea. A curriculum designed to, in Choi’s words, “destigmatize mental disorders and empower people” would be presented in an activity kit that children could use in their own individual ways. With the kit—titled Maeum, which can be translated from the Korean as “heart and mind”—Choi saw packaging design as a way to make the educational experience around emotion, thought, and perception more exciting, choosing a travel concept to tie the objects together. In a vibrant but tranquil color palette, Maeum includes a textbook, diary, colored pencils, activity cards, stickers, patches, and sewing set to make luggage tags. The items are nested in a convertible container reminiscent of a suitcase, an object, Choi said, “that can be personalized to help students express themselves through various outlets.”

From the Crit

Jae Wendell, BID ’20: What inspired you to choose the travel theme?

Claire Seonjae Choi: I was trying to get a keyword from what I was trying to present in this kit, and I came up with words that are related with exploration and understanding. I thought those words fit well with the theme of “journey.” [The textbook] helps you to guide your heart and mind. It’s kind of like a map for your travel.

Kai Chuang, BID ’20: I want to see what the activities are inside the kit with more specificity. Like what do the sewing kits look like? What would an example luggage tag have on it?

Claire Seonjae Choi: I came up with this idea of cross-stitching when I was doing an interview with Dina [Schapiro], from the Arts Therapy Department. She was telling me that artistic activities can be very therapeutic. So I wanted to add something that’s repetitive but also [makes] something creative. The fabric would look like the name tag for the luggage, and kids can sew their own pattern.

Amanda Huynh, Assistant Professor of Industrial Design: It would be a nice next step, showing some concrete outcomes from the cross-stitch kit. Maybe it is just having a co-creation with kids, with the cross-stitch set, and seeing what they would do.

Read Claire Seonjae Choi’s process book.

Kai Chuang, BID ’20: SanTsan

Cart for Community Action

Connecting people through food was a theme baked into Kai Chuang’s capstone project from the start, but it took on increased resonance mid-semester. The project, titled SanTsan (the transliteration of a Mandarin word meaning “three meals a day”), was originally conceived as a means of peaceful protest. Chuang sought to interrogate cultural appropriation in relation to food and educate and activate the public, using as a focal point a Manhattan restaurant owned by white proprietors that purported to serve “clean Chinese food.” When COVID-19 hit North America and food scarcity became a topic of widespread concern, particularly in underserved communities, Chuang shifted the project’s focus to respond to the circumstances.

Observing the way local mutual aid networks were working to assist residents experiencing food insecurity, and taking inspiration from grassroots initiatives like neighborhood food fridges and the ways in which independent food vendors serve communities, Chuang reconceived SanTsan to become a more adaptable tool. The project’s centerpiece, a food cart—designed to be made of accessible materials in an open-source, replicable format—could act as a mobile food pantry, an educational device, and/or a site of protest. In all of its forms, the goal is to, as Chuang puts it, use “sharing and genuine care to create stronger communities and also educate people on the cultural aspect of food.”

From the Crit

Alex Schweder, Adjunct Associate Professor of Industrial Design and Interior Design: I really think that your project got better after COVID. There’s a way in which, when you’re offering a protest, or doing work that is subversive . . . you want to also carve out another way, and not just be in relation to the, let’s say, the “Goliath.” If you’re always contingent upon the original big, bad thing, then you’re always defined by it. And there’s another way of protesting, which I think happened in your second half of the project, where you just started doing your own thing, rather than being against and thereby contingent upon—you instead took ways of working, took ways of cooking, took ways of eating, took ways of disseminating, took ways of distributing that were from other places, other ways of conceptualizing food, and you turned them into something that was more helpful. That’s where I think the strength of this project is.

Debera Johnson, BID ’86, Professor of Industrial Design: It’s important to understand that food is such a community experience, it’s a way to bring people together, and we share cultures through food—keeping that positive intervention is meaningful. I would ask that when you talk about appropriation, you perhaps could be . . . more straightforward. So that I don’t necessarily come to my own pre-conclusion [about what you mean by it], but you lead me to a new place that might change my mind.

Kai Chuang: That was what I was trying to do with the quote. [From the presentation: “Food is a representation of its people—their history, geography, beauty, pain, and triumph. When that context is not given the proper stage, we lose all of that, and in doing so, we devalue the people themselves.” —Stephanie Kuo] Something considered appropriative or not is not determined by the oppressor, but the oppressed.

Amanda Huynh: That also speaks to the way that Kai, I think, really struggled in the beginning, because it was something that—it was a lot of feelings, that I also feel, of frustration and anger, and how can that actually manifest in an industrial design project? And I think, in those terms, [Kai,] you’ve done really well to be able to turn it into this kind of positive making.

Read Kai Chuang’s process book.

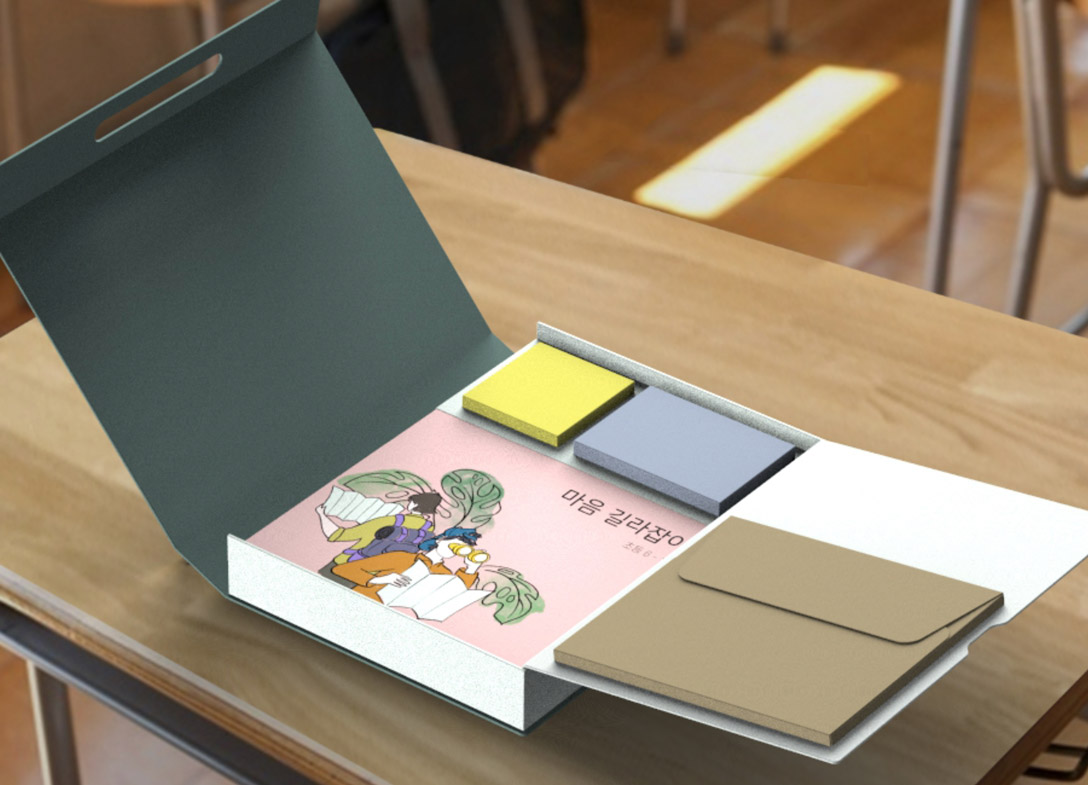

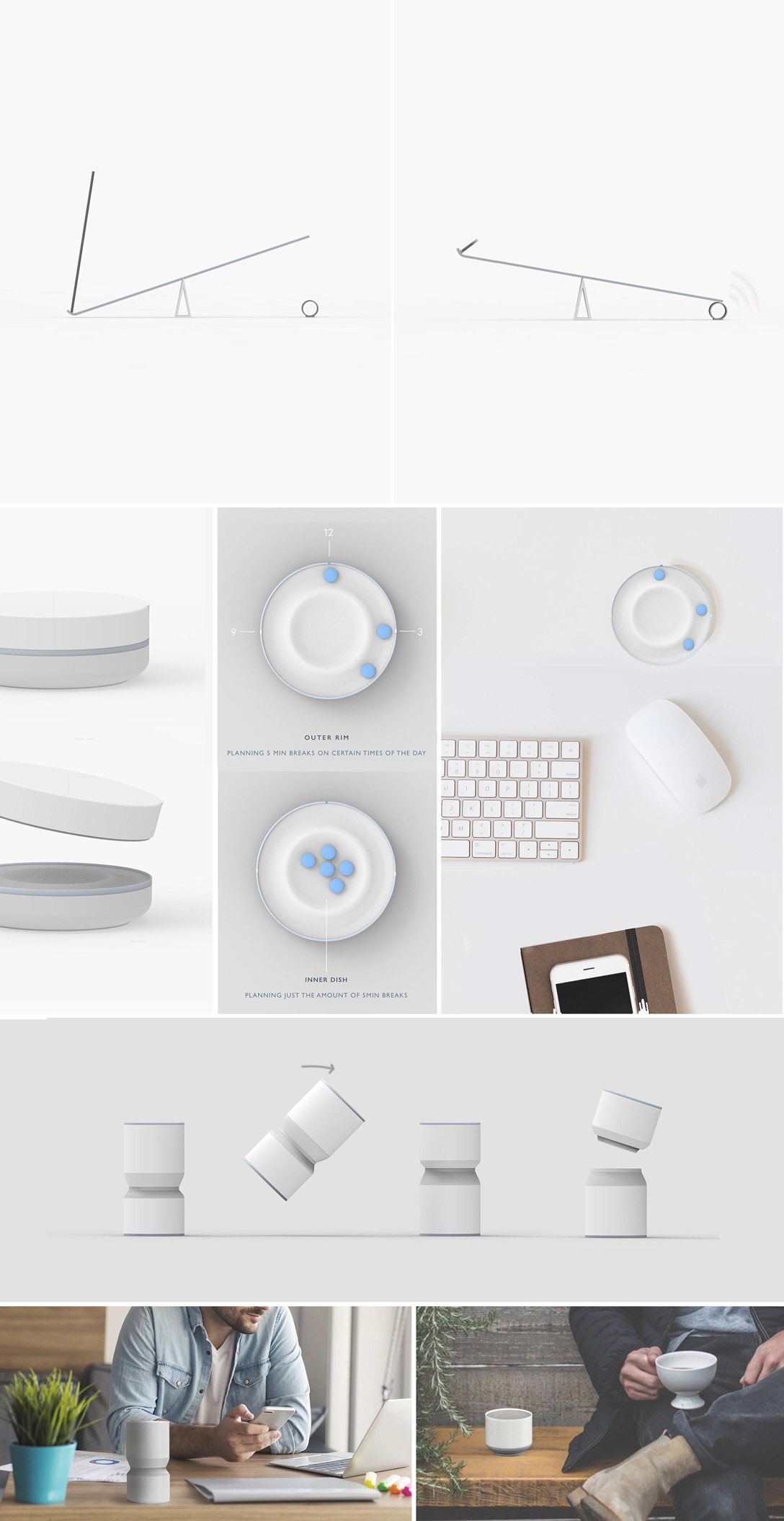

Hansol Jung, BID ’20: Break Timers

Tools for Office Workers

Strained eyes, sore backs, headaches—just a handful of the physical ailments Hansol Jung identified as plaguing desk-bound office workers. By the time Jung presented the capstone project Break Timers, these afflictions and more were making headlines, as people from many sectors of the workforce moved en masse into home-office setups during the pandemic. Not only could these makeshift arrangements be physically stressful but the overarching conditions brought on their own burdens. Everyone was being encouraged to stay inside and limit their range of activity—possibly deepening the sedentary working habits that Jung’s research showed could lead to not just discomfort but larger health problems. For the capstone, Jung chose to focus on encouraging breaks, as a potentially significant way to improve worker well-being, wherever that work was taking place.

Break Timers features a collection of objects designed to stimulate the senses and introduce periods of tranquility into a workday—a detachable, portable hourglass speaker that plays music; a clock-like dish of timer mints that dissolve in the mouth over 5 minutes; and a 45-minute incense burner for a longer break experience. “One important comment that I got from the interim crit was that these objects shouldn’t be passive,” Jung said in the project presentation, so each object has an alarm function. “I designed it so that it’s very gentle—it plays an alarm,” like the final snap of a mint, “but it’s still therapeutic and friendly.”

From the Crit

Jae Wendell: The physical function of the incense timer is so elegant.

Matte Nyberg, Assistant Chair of Industrial Design: I think that was my favorite one too, because it seems like I would very much be aware of all of the things that were happening around me—the smell, the sight of the smoke, and for sure that shift when eventually the teeter-totter hits the bell. Considering how small the object is, it’s quite a lot of impact, which is really nice.

Constantin Boym, Chair of Industrial Design: The incense burner is very inventive. It’s really quite beautiful. My question is about the [hourglass]. An hourglass has this very specific shape, iconic—you know, we even refer to it as “an hourglass shape.” And you almost decided to avoid that shape. I’m just curious why.

Hansol Jung: So I did a lot of form ideation. Because it detaches, it looked a little bit unbalanced when it’s not together. And because of that function, I changed the form to be this straight shape.

Constantin Boym: When you create a set of objects, we talk about a family of forms, so not exactly the same form everywhere, but the forms relate somehow. I can imagine the tower for the hourglass could be maybe a little more thin and elegant. Like a little statuette on your desk.

Amanda Huynh: I think we’ll see in your book all of the form explorations that you did, because I think you were trying to balance it with the ritual as well. You were trying to keep them as active objects on your desk, so you don’t forget about taking a break and it’s all falling by the wayside. . . . What’s the next step for you, Hansol?

Hansol Jung: What Constantin suggested, I was thinking about how these objects can look more like a family.

Read Hansol Jung’s process book.

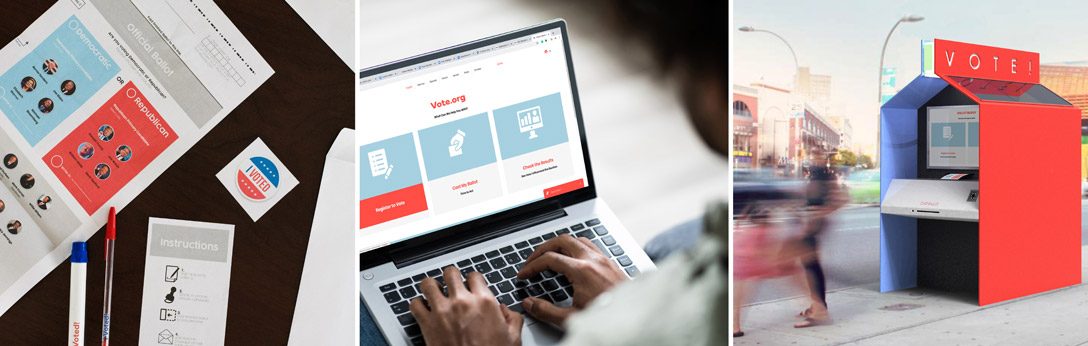

Griffin Uhlir, BID ’20: Democracy During Pandemic

Voting Systems

When the novel coronavirus began spreading throughout the United States last spring, two dozen states had not yet held their primaries in this presidential election year. Seeing how physical distancing measures and lockdowns were limiting the ways in which voters might cast their ballots and make their voices heard, Griffin Uhlir developed three concepts to address the constraints and improve the voting experience—a topic Uhlir had already begun exploring before the pandemic made it even more pressing.

“My capstone project is focused on empowering people to influence their society,” Uhlir said in the presentation for Democracy During Pandemic. “Voting is one way individuals can impact our nation. But most of all, voting is a citizen’s right. And based on my research, the existing voting system makes voting a privilege.”

The goals of Democracy During Pandemic were to “remove physical density, maintain ballot security, and limit barriers to voting.” Uhlir proposed, first, a more user-friendly vote-by-mail process, with a streamlined ballot and clear steps for requesting and returning it; then, to address the potential issue of mail-system overload, a remote, online voting platform; and finally, taking into consideration potential cybersecurity risks, outdoor voting stations that allow voters to maintain distance while casting their physical ballots.

From the Crit

Debera Johnson: My biggest concern was the use of red—it’s such an attractive color, it’s such a “do something” color that, psychologically, I’m concerned with how you used that. It’s very powerful.

Griffin Uhlir: The color is definitely a challenging part of it. And I was careful to make sure [red and blue] were balanced back and forth, but I think I’ll have to look at maybe exploring alternate options.

Alex Schweder: One of the things that occurred to me . . . it’s that [the colors are] shown as dichotomous. I wonder if they could be striped. I wonder if it could be a pattern where they’re stitched together. These are two colors from our flag. And I think that we associate these with voting. The way that color works in terms of interdependence—the blue needs the red to stand up, the red needs the blue to stand up—might be a way of communicating this idea of democracy that permits different opinions.

Amanda Huynh: I think the strength, seeing the three of these [concepts] now, is that while everyone is scrambling . . . what you’ve really done is designed for this uncertainty in a way that is so concrete. And I think that’s a really incredible feat.

Melissa Skluzacek, Manager of Resources and Technology, School of Design: Ideally, all these formats are implemented. I think this idea of a one-size-fits-all voting system is problematic at its core. The whole idea of accessibility is to broaden the framework in which people are able to actually exercise their civil liberties, so this idea of it being multifaceted is very much, I think, a wonderful kind of guide in which to move forward.

Read Griffin Uhlir’s process book.

Jae Wendell, BID ’20: In/Edible

Activity Kit for Community Connection

“How do we keep our communities nourished?” The question at the center of Jae Wendell’s capstone project from the start took on unanticipated complexity as ideas around what constitutes community and nourishment changed last spring. Wendell, who was living in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, but didn’t feel fully enmeshed in the neighborhood as a student transplant from Michigan, suddenly was connecting with neighbors every day after the pandemic hit. Engaging with mutual aid networks and interacting on the street, Wendell realized, “I need my neighborhood more than ever, and I want to provide back.”

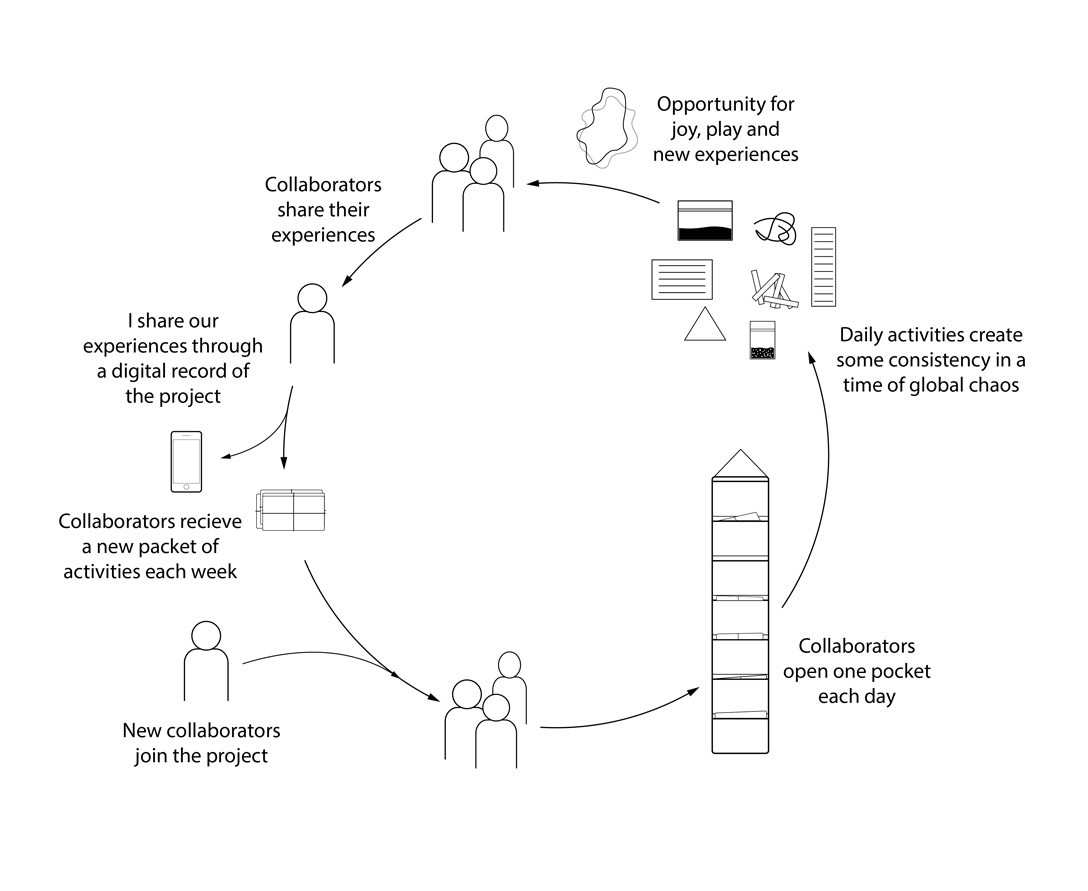

Wendell had already been researching a variety of people’s relationships with food and cooking using a design-probe approach, distributing a kit of activities participants could respond to and thus provide data for generating ideas. The playful spirit of that research method became central to the final project, In/Edible. What resulted was what Wendell described as a “daily pocket,” a kind of refillable advent calendar full of food- and kitchen-related prompts, projects, and games for each day of this challenging time, intended to be given as a gift to interested neighbors. Themes of human connection, food-waste reduction, and reflection on how we cook and eat thread through the activities. Participants would be invited to share their actions and creations via a project Instagram account, which would also show Wendell’s “strategies, recipes, struggles, and failures to reduce my own home food waste and bring joy into my kitchen.”

From the Crit

Alex Schweder: You used the word “strategies,” and that made me think of another exercise. Something developed by Brian Eno in 1975 called Oblique Strategies. If you don’t know his work, he’s a musician and composer. And when he would run into a difficult moment, he would pick up one of these cards—it’s a pack of 100 cards—and they each have a different instruction that’s not even an instruction. It’s more like “overtly resist change,” or another one is just “water.” I’m wondering, what are the strategies that we’re developing to maintain community now? I’m interested in what you develop as prompts. There’s another project by an artist named Miranda July, called Learning to Love You More, with Harrell Fletcher. It’s a series of small instructions. I wonder how [your] instructions can prompt people to cook differently, or [cook] a different kind of meal.

Jae Wendell: I love the idea of abstracting the instructions, because I think I was, in some of them, worried about a lack of instruction. But I think that I can bring that element back and trust that people will interpret things how they want, no matter how much instruction you put in there. Giving more room for people to put themselves in is an interesting approach, and I’ll definitely check out these precedents.

Amanda Huynh: On the note of the Instagram page: the Bed-Stuy Slack, which I’m also a part of, is at over 3,000 participants at this moment, so [I see this as] incredible validation for the work that you’re doing—thinking about this connection, geographic connection, as we’re all in isolation. I think it proves the point of how necessary this is to be doing—something that can join us together, to be, you know, cooking tomatoes at the same time, or the same week, as everyone else in my community.

Debera Johnson: I’m pretty new to Instagram, and I’m so impressed by the amount of photographs people take of food. Especially now, of bread—seems like everyone’s baking bread. To extend that desire to share food that’s coming through Instagram—I want to share this bread with you; I posted something last night, sharing a glass of wine with people—there’s an opportunity to expand it, give it more depth and meaning and connection. What people are clearly expressing a need for, I think you’re giving it a platform.