When campus closed last spring, and the city shortly after, these Pratt photography students were in the midst of assembling their sophomore and junior surveys.

Leaving the studio, the lab, and life as they—and we all—knew it behind, they moved to spaces where they could safely weather the storm of the pandemic and continue to develop their practice.

What did “home” look like now, how did it change their work, and from these intimate places, some steeped in memories of the past, some stirring up questions about the future, where is their vision taking them?

Photos this section by Brandon Foushee

The Light Inside

In his junior survey project, An Internal Space, Brandon Foushee, BFA Photography ’21, examined the subtle atmospheres of interiors, human and physical. In many senses, the people who are his subjects appear in a state of “home,” whether going about a relaxed afternoon in a shared apartment or cast in a warm beam of light before Foushee’s tender lens. Central to his work is celebrating, in his words, “the daily routine of life . . . to challenge expectation and interpretation,” framing the “thriving, active moment which has been underrepresented in the depiction of a more nuanced perspective of Blackness.”

As the place Foushee called home changed in the midst of the pandemic, these explorations of intimate spaces and movements became a way of orienting himself. Even as familiar casual interactions with friends and habitual motions of a day were altered, the practice of engaging with the atmosphere of the everyday remained, a way into a conversation about Black experience and the resonance of the ordinary.

Where was home for you this spring/summer? And is that changing at all this fall?

Home for me this summer consisted of my bed, roof, and bike, as I have been staying in Brooklyn, New York, and plan on staying there this fall.

This spring, when home became the primary site of your work, did that begin to change your process or the way you thought about your work?

In the beginning, it did not really change the way I had created my work. I was towards the end of creating a series for a photobook, which still felt possible to do from home. The things that did change were the types of images I felt comfortable making. I photographed the diffused light in my living room at my apartment, which was a freshly new spot at the time, as my lease ended in March and I had moved into this new [place] that last week in March.

Did the work you were creating change the way you felt about home—as a specific place, or as a concept?

I think the work informed the new space I was living in. It did not feel like home, but I knew it would right away. The photographs I made helped me get familiar with the space that I would live in all summer.

What constraints did you have on your work that you didn’t have before? How did you find yourself adapting in order to work within them?

The constraint I had tied with making my work was, of course, leaving the tactile part of photographic printing. I created digital PDFs of my photobook instead of a physical [object] (I am still working on the physical now).

As we sit on the cusp of the new semester, how do you see your work evolving? Has the experience of being at home influenced the way you’re thinking about this next year’s projects, or your thesis?

I want to make my work way more accessible. I was working on this goal about a year ago, but now, of course, the timing has aligned. This does inform my decisions on creating my thesis, but I wouldn’t go as far as being disappointed at the lack of resources. I am the type of person where having too much freedom and no limitation makes me freeze and not create work.

Photos this section by Audrey Kenison

One Last Look

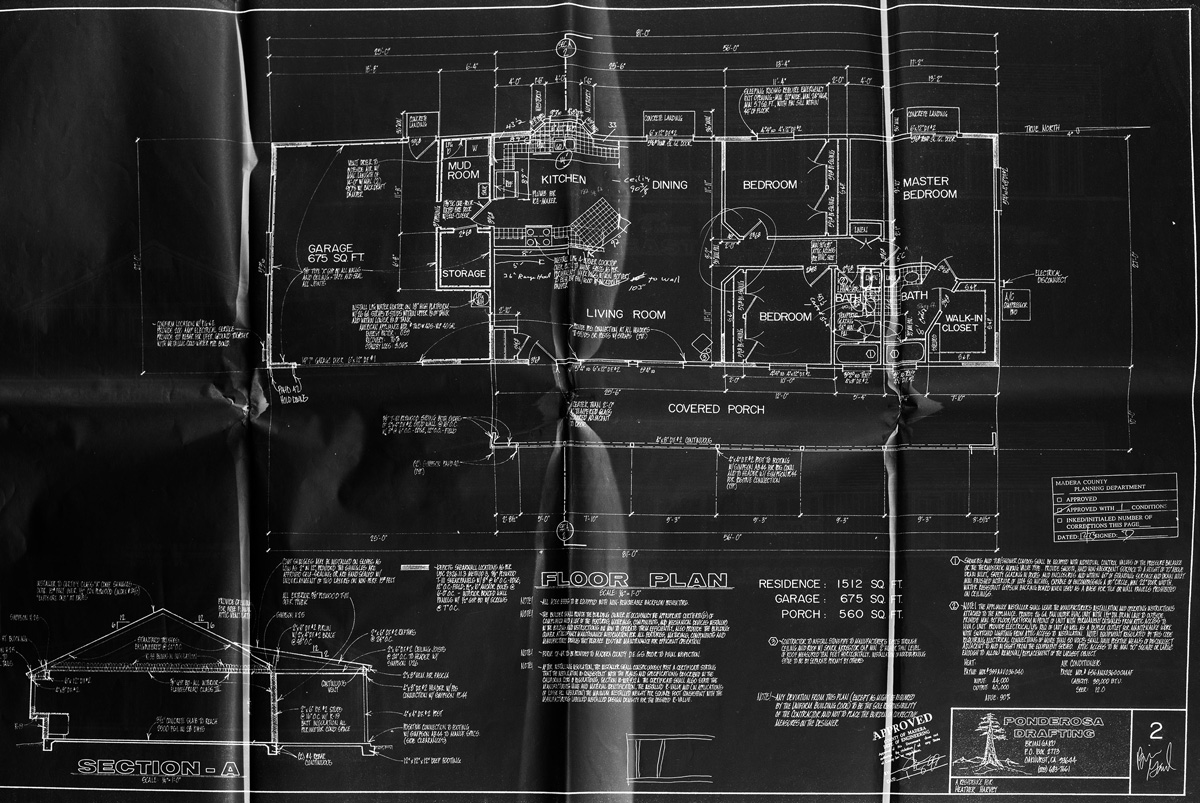

“Though everyone has lost something due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I have gained a new perspective on my hometown since returning,” Audrey Kenison, BFA Photography ’21, wrote in the statement for Vulture Days. Kenison dedicated this junior survey project to defamiliarization—to “dissect the domestic” in a place at once familiar and strange within the context of the pandemic. That grappling with the known-unknown was a universal experience this year, made more complex on a personal level by the fact that Kenison’s parents were preparing to sell their home. “At no time has the concept of the uncanny resonated more,” Kenison says.

Where was home for you this spring/summer? And is that changing at all this fall?

After the residence halls closed mid-semester, I relocated to my parents’ house in California, where I spent most of my childhood. They live about 25 miles north of Fresno.

Now I am in Spokane, Washington, in my parents’ original house, the house in which I spent the first three years of my life before they moved back to California. It is a town and a house that has always held a mythical status in my mind, because I remember almost nothing about it. For both my parents and me to call it home again is nothing short of surreal.

When home became the primary site of your work, how did that begin to change your process?

Working at home did change my process, but it also clarified the foundation for my artistic interests. I was forced to contend with my immediate environment, to make it inspiring, to alienate myself from something familiar.

Working in and around the home brought on the realization that places drove me. Exploring the feel, the look, and the history of a given location always seemed to be my starting point for making work that kept me interested. To this end, working at home made me understand the advantages of access when it comes to documentary [photography]. Though my goal was to draw distance between myself and the home, in doing so, I became more comfortable with photographing my family members candidly and involving them in the creative process.

Photo by Audrey Kenison

How did the work you were creating change the way you felt about home—as a specific place, or as a concept?

I wasn’t sure how to feel about my parents selling the house in California. Making work about the home showed me how I felt. There was a sense of liberation and closure. If something so familiar could become strange again—there was a lot of possibility in that.

At the house in California, I was a spectator, but as a family member, I was [also] privy to all the dinner-table discussions, cocktail hours, and talks in front of the TV. Without my academic community, my neighborhood in Brooklyn, and most of my belongings, my parents’ life was so much closer than before, nearly all-consuming.

Home is always moving. Home is falling in love with an idea. Home is positioned somewhere between the mundane and the mythic.

What constraints did you have on your work that you didn’t have before? How did you find yourself adapting in order to work within them?

We were without even a basic black-and-white printer. I was lucky to have borrowed some photo equipment from Pratt and have a laptop for working on digital files. I had no access to film, labs, or printing facilities. The work was strictly digital and viewed digitally. Before the coronavirus outbreak in New York, I had dedicated a year to my project exploring Brooklyn’s Barren Island, better known today as Dead Horse Bay. I had to put the project on hold indefinitely when I was forced to return to California.

What would I create for the remainder of the semester? I would walk around the old neighborhood and take photos as a way to relax. Luckily, my parents’ plans to fix up the house gave me a specific subject on which to focus my efforts. If my childhood home was being sold within the year, it only felt right to document it to the best of my ability.

I’m never one to miss a unique opportunity. Working on something with such a small scope was the opposite of my former project, but it lent me more focus and speed, both of which were necessary given the situation. Presenting everything digitally allowed me much more experimentation in critique and I was able to make new associations that might not have registered as prints on a wall.

As we sit on the cusp of the new semester, how do you see your work evolving? Has the experience of being at home influenced the way you’re thinking about this next year’s projects?

When I realized that my creativity is stimulated by a meditation on place, it wasn’t hard for me to start taking photos in Spokane and see where they would lead.

My work ends up producing little archives of sorts, except they boast no objectivity. Everyone in my family says I’m just like my grandmother. I move like her, I’m just as curious, I have the same passion for places. She has always been the family photographer. Being home and having access to the family archives made me wonder what could happen if I started working in dialogue with her pictures. I could work in the present and the past simultaneously, and sometimes I could see the future.

Then I couldn’t stop thinking about time, but not in the usual way that reminds us of our mortality. It was more like in-betweenness. This sense of liminality only grows stronger the more I am able to survey Spokane. My parents always say, “There’s a unique culture around here.” I’m trying to picture what they mean.

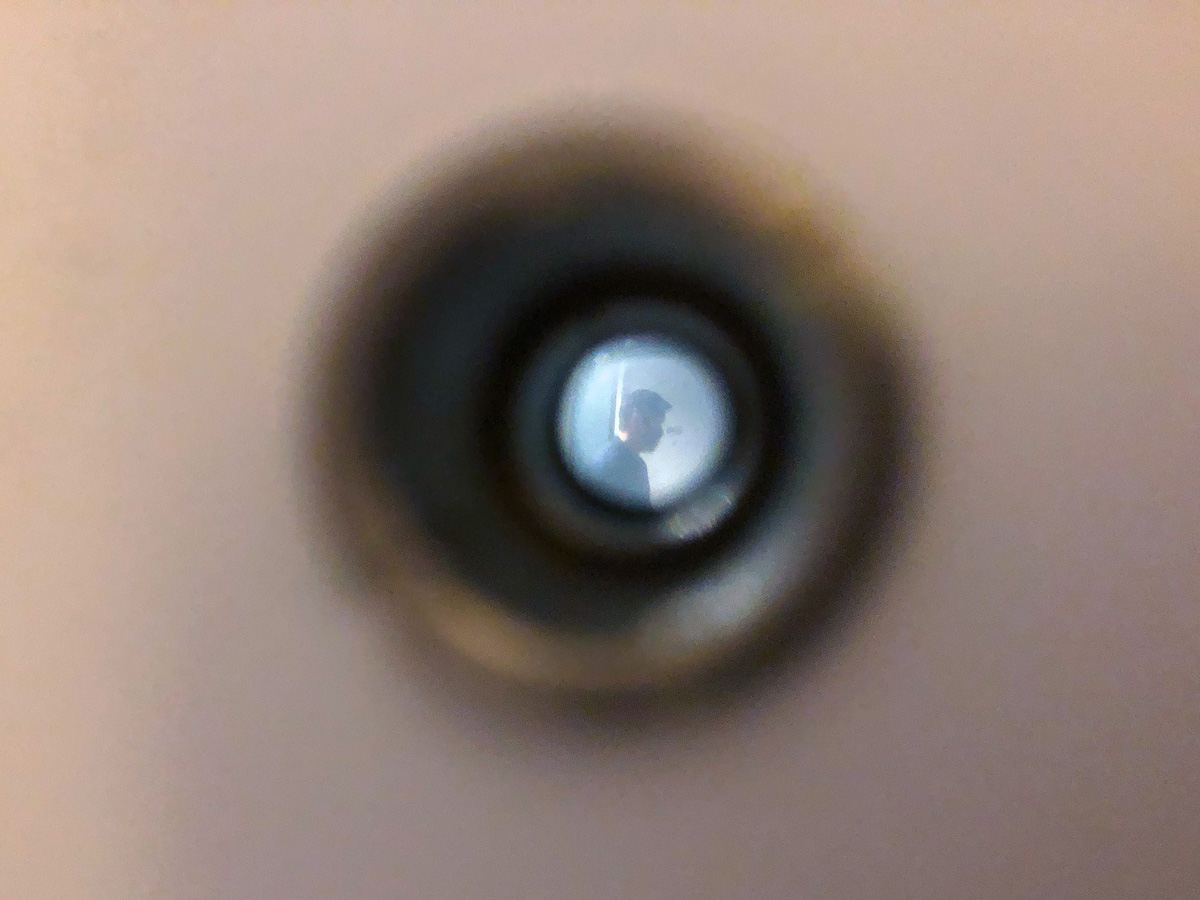

Back to the Present

When Kristen LaSalvia, BFA Photography ’21, began her junior survey project Don’t Look Back, You’re Not Going That Way, it was a way to understand her origins, at a distance—the space between Brooklyn and LaSalvia’s hometown in Florida. Returning to that childhood home this spring was an unexpected opportunity, a way of reckoning with sometimes haunting memories of the past in the place where they were formed, and confronting the uncertainty of the future, while uncovering, with a rare immediacy, the promise of the present.

Where was home for you this spring/summer? And is that changing at all this fall?

Home for me this spring/summer was primarily my mom’s, where I did a majority of my growing up. I occasionally bounced between there and my dad’s house. I’m now back in Brooklyn attending classes, but will be going back home for the winter holidays.

When home became the primary site of your work, how did that begin to change your process?

My project began by focusing on my relationship with my mother. It was a struggle to create imagery that spoke on that from such a distance, as I was here in New York while she was home in Florida. The pandemic allowed me an opportunity I wouldn’t otherwise have had to be completely immersed in living with her again for such an extended period of time, which hasn’t happened since I was in high school, maybe even middle school.

How did the work you were creating change the way you felt about home—as a specific place, or as a concept?

It was a weird and bittersweet feeling being home. It was like a sense of nostalgia was constantly hanging over me as it reminded me of being a child again, yet that nostalgia held an edge of anxiety as much of my childhood was shaped by having an alcoholic parent. If anything, I think being there helped me reach a place beyond the resentment I had been holding on to and gave my mom and me a chance to bond in a way we never have.

What constraints did you have on your work that you didn’t have before? How did you find yourself adapting in order to work within them?

The constraints boiled down to simple technical issues of not being able to develop film like I would in New York. I was also experiencing a lot of creative fatigue, and a sense of nihilism was weighing me down. Because of this, I pared down my images to simple iPhone photography in order to have more freedom of taking images without overthinking it.

As we sit on the cusp of the new semester, how do you see your work evolving? Has the experience of being at home influenced the way you’re thinking about this next year’s projects?

I’m beginning my senior thesis, and I see it as an extension of this precious project, as it focuses on the broader topic of inheritance and what that has meant for me and my family. Being home gave me the chance to really visualize the way in which I have been shaped by those before me.

Photos this section by Danielle Van Winkle

Origin Stories

For Danielle Van Winkle, BFA Photography ’22, moving away from a small West Coast town to study in New York City had been intentional, peeling away from manicured, “glaringly perfect” environs to seek out more unexpected beauty. Most often that beauty manifested in people—especially girls, whose relationships Van Winkle had been exploring with an affectionate, intimate lens. When the pandemic forced her to return home back west, Van Winkle rose to the challenge of contending not only with the absence of her usual subjects but also with a place that she had been at odds with, discovering it with new eyes and pushing the boundaries of her emerging practice.

Where was home for you this spring/summer? And is that changing at all this fall?

Davis, California, a small town nestled in between San Francisco and Sacramento. I came back to Brooklyn in June and plan to be here into the near future.

When home became the primary site of your work, how did that begin to change your process?

Coming back home made me realize how beautiful California really is. Not to disregard New York City’s own unique beauty, but sometimes you just want to see some greenery, you know?

Normally a portrait photographer, I decided to try out landscape photography for my sophomore project. I drove up and down Northern California, stopping at little towns I stumbled across here and there, exploring from the safety of my car.

How did the work you were creating change the way you felt about home—as a specific place, or as a concept?

Shooting Northern California every day started to wear on me in ways I didn’t expect. Everything started to feel too beautiful, too similar; almost Stepford-Wifey, for lack of a better term. I missed the grit and bustle of New York, I missed having everything right there when I needed it. Every town felt the same picturesque way. My work slowly morphed into a critique of white-fence society as the project progressed, less appreciative and more cynical. I suppose the grass is always greener on the other side.

What constraints did you have on your work that you didn’t have before? How did you find yourself adapting in order to work within them?

Social distancing pretty much eliminated portrait photography as an option for me. Learning to photograph landscapes is a completely different process. It was a bit of a learning curve, but having a car to go places definitely aided in my success.

As we sit on the cusp of the new semester, how do you see your work evolving? Has the experience of being at home influenced the way you’re thinking about this next year’s projects?

Shortly after I concluded my sophomore project, fires completely tore apart Northern California. Most of the places I photographed for my project burned down or are in danger of burning as we speak. Suddenly I became homesick for somewhere I could never go back to. I went from loving what I photographed, to hating it, to loving it again. This project taught me to appreciate what’s there while it still exists.

Photos this section by Youchen Zhou

Where Is Your Home?

Last spring’s unanticipated long trip home to Singapore for Youchen Zhou, BFA Photography ’21, was a study in contrasts—the cavernous, wide-open spaces of airports devoid of travelers followed by an isolation period, but under the constant surveillance of government monitors; the well-appointed hotel room, mandatory for an international traveler to quarantine in, that, as the days ticked by, transformed into a cell of loneliness and confinement. All of this came alongside the pivot of Zhou’s practice, one day based in photographing people in a bustling urban habitat, and the next, making work about spaces where, suddenly, people had disappeared from the scene. At once, heading home meant traveling into uncertainty about where exactly “home” might be.

Where was home for you this spring/summer? And is that changing at all this fall?

I moved back to Singapore temporarily for spring/summer as I did not have a place to stay after Pratt shut down their [residence halls]. For the upcoming school year, I will be moving back to Brooklyn in a rented apartment.

When home—or in your case, the spaces you encountered on the long journey home—became the primary site of your work, how did that begin to change your process?

The documentary project on my flight journey was created unexpectedly as my original project for that semester was on street photography. I am unfamiliar with taking photographs of surroundings, as I was more comfortable in working with portraits/people.

How did the work you were creating change the way you felt about home—as a specific place, or as a concept?

Home for me is a safe place where I can be comfortable with myself and the people around me. I do not feel the sense of belonging back in my hometown, Singapore, as I do not fit into the ideas and lifestyle. Perhaps it would take a while for me to discover a place that I could call home.

What constraints did you have on your work that you didn’t have before? How did you find yourself adapting in order to work within them?

Due to the virus situation, I would not be able to interact with people or be exposed to more people for my projects, which affected my usual way of exploring new ideas. I would like to move towards other topics and/or mediums that I have always wanted to try. It might be beneficial in the long run to venture into different directions and not to be confined by one medium or artistry style.

As we sit on the cusp of the new semester, how do you see your work evolving? Has the experience of being at home influenced the way you’re thinking about this next year’s projects?

The long hours of staying home have made it harder to come up with new concepts for upcoming projects, as most of us do not have new events happening. I would like to move away from portrait/people projects such as street photography or documentary and work towards a more graphic-design approach to my senior thesis.