Along St. Ann’s Avenue in the Bronx’s residential Melrose neighborhood, a stretch of polished metal fence, woven at intervals with curved protrusions, invites residents to stop, sit, and take in their reflections against the backdrop of their street. This is the vision of Bronx-raised artist Borinquen Gallo, adjunct associate professor of art and design education at Pratt Institute, who is working to address complex questions around community relations in a commissioned installation, currently in the conceptual proposal phase, that would sit just outside a new building for the 40th precinct of the New York City Police Department designed by architecture firm BIG.

In 2016, Gallo was selected to create a work for this site through New York City’s Department of Cultural Affairs Percent for Art Program. Her on-the-street research, which involved speaking with neighborhood residents as well as NYPD officers, and her search for common ground between the often polarized groups won the approval of a panel that included representatives from both.

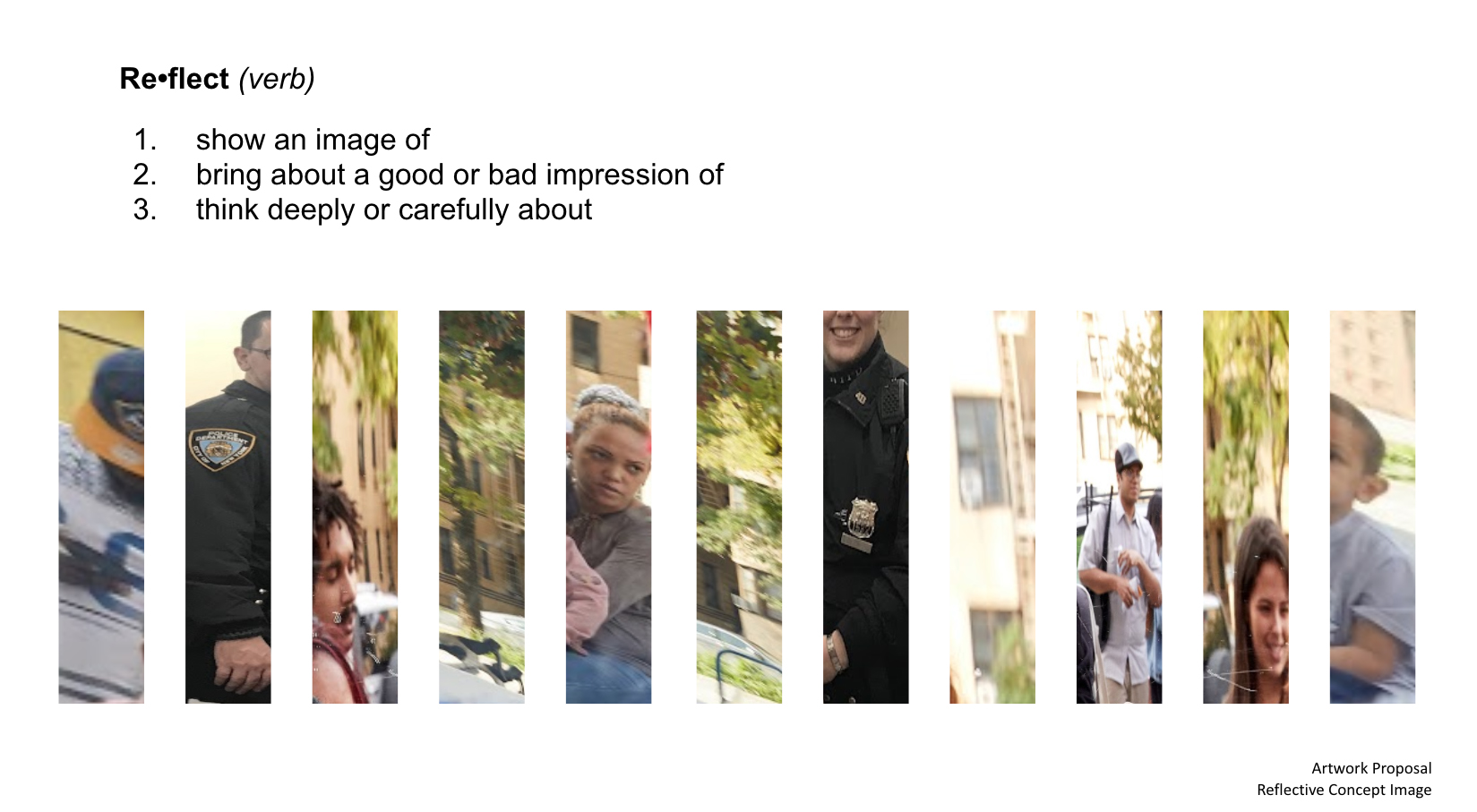

Since then, Gallo’s conceptual design proposal has moved through a few variations, a process that the artist considers part of the art itself—advancing an ongoing dialogue that has highlighted the intricate mesh of the people she intends to reach with the work. Gallo brought that mesh, quite literally, into her proposal. The proposal imagines a mirrored-fence installation integrated into the architecture of the outdoor space along the sidewalk, formed using a weaving concept that threads through much of Gallo’s work—which incorporates materials like caution tape, plastic bags, and rags to form sculptural objects and installations, sometimes with the participation of local community members.

The Percent for Art project, as she sees it, is an investment in creating welcoming, inclusive spaces that could help people think in a new way about how we function as a community.

“To create the future we want, we cannot do it in silos,” Gallo says. “We have to do it through dialogue and collaboration, dealing with our differences and finding common ground somehow.”

Gallo knows that vision is a tall order, with fraught histories and power dynamics always at play, which her experiences residing for much of her life in the Bronx have underscored.

“It’s a struggle to find common ground,” she says. “We speak a lot about communities, but we often conceive of communities as separate, isolated groups that inevitably end up ‘othering’ each other. Really ‘community’ should be the ability of different people to become part of the same group.”

To that end, while the symbolic aspects of the piece are important—“the metaphor of weaving pointing to the need to unify the social fabric of our community,” as Gallo says, “and reflection pointing to the need to mirror or identify with one another, without which that unity is unobtainable”—Gallo looks to initiate physical engagement as well. The art’s functionality as a resting place and mirror serve part of that purpose, but sparking engagement has also meant thinking about how an indoor community room that is part of BIG’s design for the new precinct, the first dedicated space of its kind in a police station house, might be programmed and activated.

As Gallo works to realize the proposal in physical form, all of these considerations will be top of mind. In a sense, though, the work is well underway: a piece about voices from a spectrum coming together to think together about belonging, what connects us, and the power of art to help us imagine our future.

Read more stories from “Start Here” in the Fall 2022 issue.