From my years teaching architecture, one studio in particular stays with me to this day.

It focused on a concept for a multiunit living space that crossed generations and family makeups with the flexibility to accommodate inhabitants’ changing needs and relationships through their lives. As someone for whom home means community, it was an amazing opportunity to rethink housing with my students. The class prompted them to disrupt a conventional idea of a home and housing, opening doors to imagination and innovation, and moreover, the project encouraged them to deeply consider how we live, over time, in relation to our work, and in society with others.

Today at Pratt, new dimensions to this kind of exploration are unfolding. Amid a national housing shortage and affordability crisis that impacts urban and rural communities alike, we add to those considerations how we make our spaces within a rapidly shifting ecosystem, among a multiplicity of species, designing for environmental and social justice and equity, with the complex dynamics of New York City as the context for our examinations and work.

Questions rising out of these concerns are woven through work all over Pratt and in the work of our alumni, whether it is designing spaces for elders, investigating how we organize our communities, considering how knowledge is passed down in domestic environments, or making art that contemplates the very meaning of home.

In our School of Architecture, the question How do we live together and share the built environment? is at the center of a provocation, Cohabitations, which this year is bringing together housing-related work from the four departments. At the start of the fall semester, I sat down with School of Architecture Dean Quilian Riano to discuss housing, as a means to address a basic human need but also a space to think about care, community, and understanding of our place in the world.

—President Frances Bronet

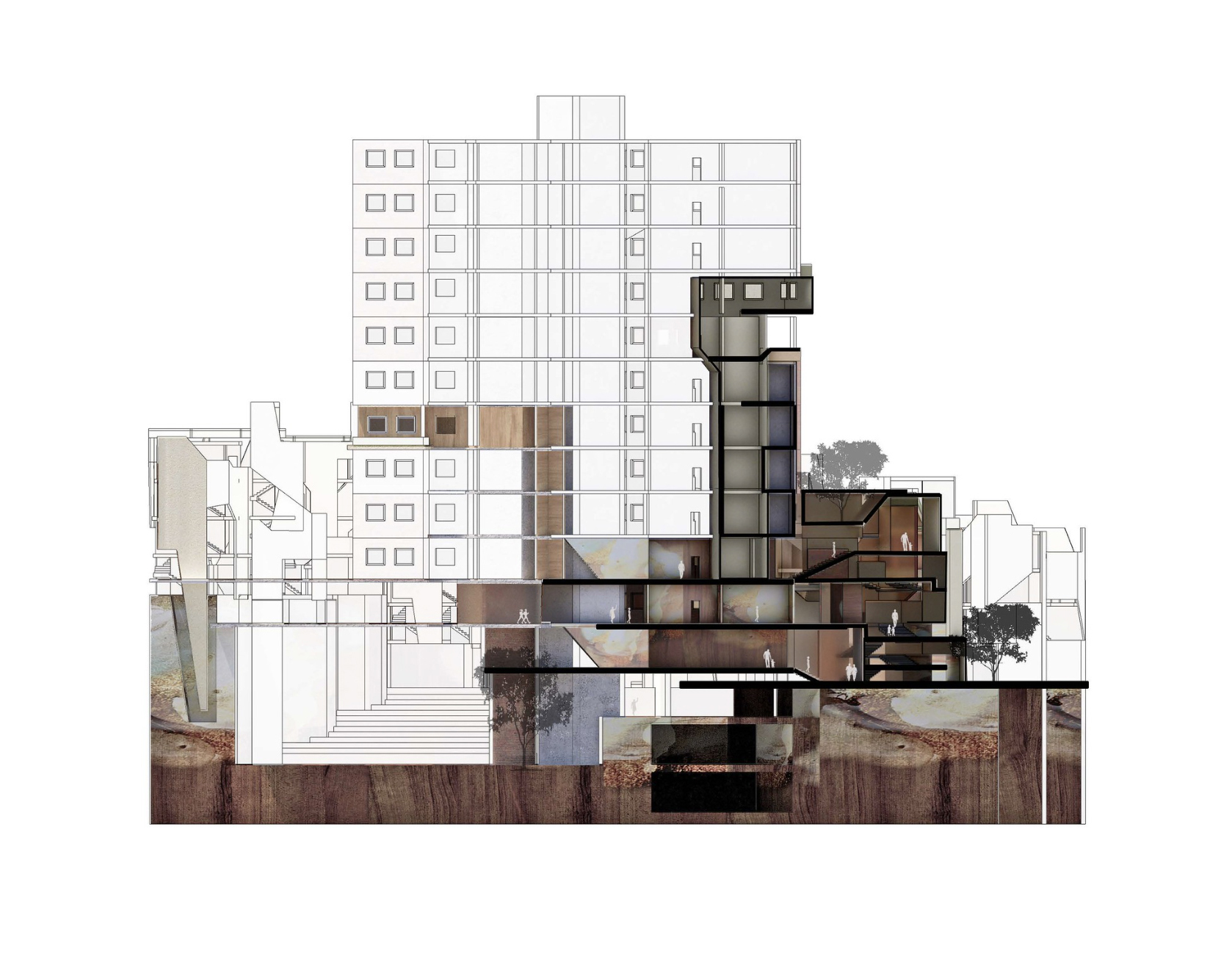

Frances Bronet: The subject Cohabitations is fascinating—it brings up a class I used to teach, in the first year, second term. The project was “variable-commitment housing.” The central question was, How do you design for residents of a multiunit building, of different ages, occupations, family structures, to allow for their commitment to how they live in the space to shift, based on fluctuations in their lives and relationships? While they weren’t going to fully resolve this problem, the students came up with amazing proposals that made them rethink how people live together, and to consider the fact that our lives are not static, and that we don’t know who we’re going to be 15 years from now.

Quilian Riano: Housing is one of my favorite topics to teach in design studios—and I’m excited to hear that, in your case, it was introduced so early on—because it forces students to confront what exactly a house is, questioning every aspect of everyday life. Thinking about housing is a tangible way to wrestle with big issues of social justice, equity, and environment, and reimagine the relationship between labor and living. It’s a mix of the theoretical and the radically pragmatic.

I find the housing model interesting because it’s something that we all have experience with. When I was going through architecture school, a lot of the programs were a museum, a ballet, these larger performance spaces, and you may or may not have had experience with the content in those spaces. But everyone lives somewhere, everyone has a family structure, and societal and other structures are reflected in that. So you have a place to begin.

In the context of design education, in which we encourage students to take every new program, every new exercise, as an opportunity for experimentation, you can bring that experience—we all sleep somewhere, we all eat somewhere, we all share somewhere—and then start to wonder.

For example, we look at precedent studies, like what is happening now with senior housing in Japan, that we can learn from, in terms of sharing spaces, sharing structures, creating new sets of communities, that can be applied anywhere.

So, that’s one of my favorite things about housing. It starts with the lived experience and the body, because you know what it’s like to live in spaces, and it begins to put that experience in a context, especially when it’s a multiunit housing structure that you’re designing. What does the unit mean? How does it aggregate? You can call a unit an apartment, or it could be a unit that is closer to what you were describing, this more mutable structure. What does it mean to then turn it into a building that potentially has extra spaces for sharing, or for the unanticipated? And then how does that fit within a larger community?

FB: I grew up in affordable housing, where everything met minimum standards, the windows were of easily manufactured dimension, bathrooms were five by seven, ceilings at eight feet. And I spent almost no time inside of that space. I was always on the street or at a local Y-sponsored “Neighborhood House” (the street was not that hospitable in Montreal winters). So for me, housing is the community. With housing, you also think about the space beyond the inside and how we develop relationships and other layers of engagement with the world.

I think about Hull House in Chicago, designed at the turn of the last century. It was a social settlement, committed to the community. It was a residence, a research entity, and a vehicle for social reform. That would’ve been a great thing for someone like me. You have a chance to retreat into your own space, but you also have a place to be with others, responsible to the neighborhood. In many cases, we’ve stripped that away. So there are these great models. What are the other models?

QR: I’m also fascinated by the fact that [professional and trade] unions have built co-op housing and other models in New York City. Another, historical, example I’m fascinated by is Finntown, where Finnish immigrants in Sunset Park created a series of cooperative housing and business models. So, there might be models from our past that can help us create new ones for the future.

FB: Also, our students are coming from different kinds of living arrangements. How can we take wherever they’re coming from and use their histories and experiences as valuable contributions?

Now, in the US, we’re grappling with the cost of housing. One issue is we’ve made the rules around housing so demanding—windows have to be a certain size, you can’t live in certain basements. (Though the Pratt Center is doing incredible work in that area.) We’ve actually made sure that people can’t have housing, because the restrictions are so demanding. What do we have to rethink so that people do have the appropriate accommodations? We’ve eliminated a certain kind of richness in the spectrum of possibilities.

QR: We began talking specifically about design—but the policy part is so important. Housing reflects society; it reflects our societal goals.

In the School of Architecture [SoA], all the departments, all the programs, have something they can do around the issue of housing, whether it’s the community planning or the policy, the real estate planning and management, or the design of buildings, landscapes, and public space—these built-environment elements come together in a cohesive way.

Working with NYCHA on public housing, with the community in Red Hook and Farragut Houses, we are thinking about some of the issues you’re talking about around equity and the challenges of public housing at this moment. In the undergraduate and graduate departments, there are studios looking at how we build onto these developments, how we think about the landscapes, how we bring in more programs. Some of this can be inspired by what’s happening in Europe, where on the outskirts of the major cities, the kind of tower-in-the-park housing has been renovated.

In planning, we’ve been working with groups in the Lower East Side to think about how to remove fences, how to bring life back into some of the landscapes there. Our Pratt SoA Real Estate Practice program is looking at how to use systems to create more affordable housing for more people, even while questioning what “affordable” as a policy statement means.

There is another set of inquiries from faculty who have been looking at the issue of suburban housing. What does it mean to build new, with the environmental concerns, and how can we reimagine existing housing? That actually links to Governors Island, which has become a space to experiment, using the houses there, and the potential to add other structures, as a way to think about adapting for the climate crisis that our region is going to face. [Editor’s note: Pratt occupies Nolan Park Building 14 and is also a core partner in Governors Island’s future New York Climate Exchange.]

FB: And as you’re saying, this extends beyond the city. It brings to mind Michael Pyatok, BArch ’66, who has done significant work in affordable housing for low-income households (and his book, Good Neighbors, is an important resource in this space). His work touches on density in relation to urban developments and single-family dwellings, occupied by extended families and friends, and how we build communities in all of these settings.

How do we build in a way that accommodates multiple cohorts to live?

I think there’s something to looking at the sort of fantasies of how we want to live together, or not together, and then when those ideas break down, why didn’t they work? I think about housing in America that we did ultimately take down, Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis, for example, and Cabrini-Green in Chicago.

One of the great things about housing, and houses, is we have so many examples.

There are so many proposals that we can look at internationally and over time, whether it’s Incan housing or from the Global North, how people respond to climate conditions, as well as the need to actually be close to certain things and people in order to survive.

QR: In Arizona, for example, there is urgency to those issues, as seen in the high heat that Phoenix experienced during this summer’s heat wave record of 31 days with temperatures over 110 degrees. Maybe there are new typologies that are necessary to be able to create that experience that you described of life happening outside the house. All of a sudden, housing has to respond to this major moment that is only growing.

As another example, I want to mention StuyTown, which is seen as middle-class housing, but right now has an interesting mix of senior housing, NYU dorms, and apartments with a lot of families with children. Because of the focus on maintenance, there’s not much of a difference between [the buildings]. The hidden aspect of StuyTown that I think also makes it thrive is its landscape. Every building has an entrance on two floors, which makes the landscape constantly undulate and create differences between the buildings.

It’s not a perfect model—MetLife [the original developer] forbade any public uses within it because they wanted it to be seen as private. So there’s no school, no post office, but there are other things. As you probably know, it was sold in the largest residential real estate deal ever. And [the new ownership] began to add things to reflect that dorm-like quality. There’s a coworking space, there’s a cafe. There’s a place where people can do yoga and another place where kids do shows. So there is some of that community infrastructure, though it is a less diverse place than most of the surrounding areas.

FB: Care becomes so important, and issues around maintenance. That people feel cared for collectively.

So, in terms of a pedagogical tool, housing cuts across everything. It cuts across scale—you can do a single unit, an apartment building, a neighborhood. It can be distributed, it can be very dense. It cuts across materials. It cuts across issues of community and the infrastructure needed to support it; it generates empathy.

QR: In our housing studios, students are putting almost everything that we’re teaching them into practice. We invite experts in different fields and structures and mechanical systems to come and work with them. So that’s how important it is in our pedagogy.

Again, it really shows the best of what we hope our students will gain from this education. Housing is shaped by our society and the way people live, but it can also shape those things, and when they understand that relationship, that is the moment where I have seen students “get it,” you know, fully realize the potential of design and policy.

Related Reading

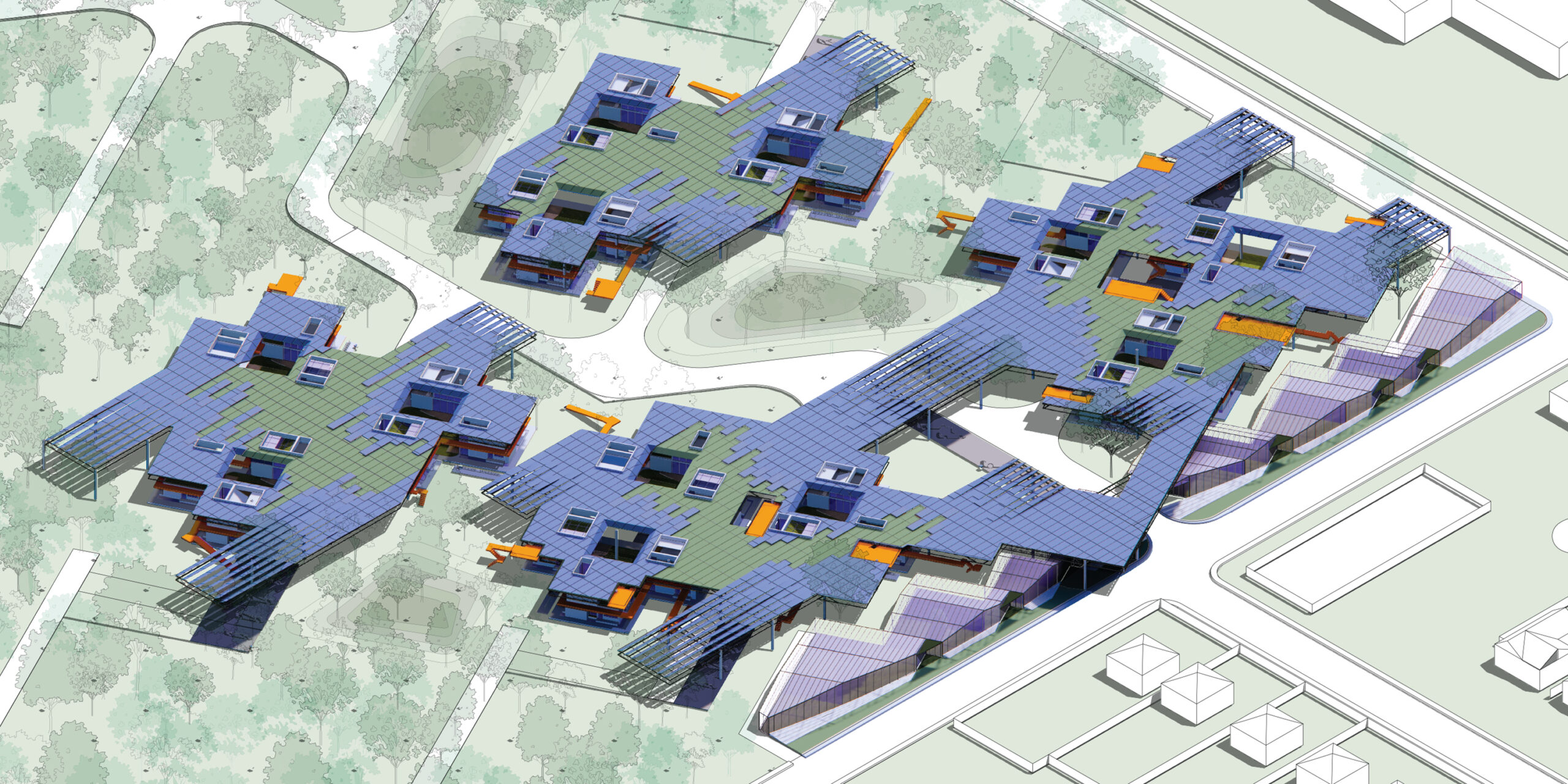

Designing a Future in Self-Sustainable Housing

In the studio Energy Collectives, Pratt architecture students consider resource sharing and co-living models to address critical issues around the housing crisis.