Moving through this transformational time, how we engage with the world is significant to how the future takes shape. At Pratt, our students and graduates are taking up the charge with agency and optimism, working in civic roles, launching sustainable businesses, screening and showing their thought-provoking work, speaking into complex narratives and facing challenges with critical reflection and care. Our faculty too are practicing in design firms, cultural institutions, and research groups that move the needle on sustainability, access, and equity; they are publishing literature and scholarship, creating personal and public artworks, and presenting in exhibitions that give voice to the experience of the moment and move conversations forward around the globe. You’ll read about just some examples in this issue.

Pratt’s presence resonates on a local level too. Thirty percent of our 60,000 alumni are living and working in New York City, integral to making the city what it is and will be, as both professionals and citizens. Pratt’s Center for Art, Design, and Community Engagement K–12, which includes the Saturday Art School, is building pathways to creative futures with some 1,000 NYC students every year. More than 60,000 K–12 students have passed through these doors. The Pratt Center for Community Development is driving research and initiatives around safe, affordable housing and sustainable energy for low- and middle-income city dwellers and supporting partnerships among local organizations and Pratt faculty, staff, and students advocating for a more just city. Across the Institute, we are working with numerous community partners, from the Brooklyn Navy Yard Development Corporation and City Tech to the Brooklyn Botanic Garden, on projects that enrich our students and share Pratt’s expertise with the community.

As we embarked on a new academic year, in which the Institute celebrates its 135th anniversary, and a new chapter with our recently appointed provost, Donna Heiland, Donna and I sat down on the Brooklyn campus to discuss Pratt’s place in creating a future with greater adaptability, richer collaboration, and more voices at the table.

—Frances Bronet, President

Frances Bronet: I often begin by invoking Herbert Simon, how the work of design is to change existing situations into preferred ones. At this moment of disruption, we sit in a distinct institution in which people are makers. There is extraordinary optimism embedded in that process, of seeking out solutions, of putting work out into the world. Our students, faculty, and alumni are doing the work of imagining what’s possible, defining what’s next, and the same goes for Pratt as an institution.

Donna Heiland: We are poised to lead as a creative institution, and this moment, when our routines have been disrupted and we’ve been forced to rethink how we do all aspects of our work, is an inflection point. Research on creative organizations tells us that the qualities that make them creative are openness to risk taking, to iteration, willingness to set up situations in which diverse individuals come together to solve problems. They support people by giving them time and space to think, to iterate ideas and processes. This is in our DNA; it’s what we teach our students to do. How are we working this way in our own professional and institutional practices?

At Pratt, we have people coming together from all across campus to think through everything from how staff structure their workdays to the core business of how we teach our classes. Thinking of our faculty, to create the conditions for them to do what they do best, we also want to think about what we ask them to do now that we didn’t ask, say, 20 years ago, and of course about the changes wrought by the pandemic. I think about related issues when I think about the work that our staff members do—the pandemic changed things for them too, but even pre-pandemic, the world was moving to a more holistic model of work.

FB: We have to remember that a large number of our faculty are sitting in practices. If we think about how this moment in time has also affected their practices, we have a complete ecosystem—the work we do in an academic environment is impacting the nature of their work, and their work is impacting our work. We can own that larger system.

There’s an opportunity here that’s really magical, but also very daunting. What’s truly going to shift, and sitting in the Office of the Provost or in the academic side of the house is this question of what you hold on to, what is actually foundational, and what offers an opportunity to shift?

I think about the projects I saw at last spring’s architecture presentations, so much work about insertions into existing structures, regeneration, renewal—utilizing the materials, the labor that produced the built environment, it’s the most sustainable thing we can do, because existing buildings have this embodied energy.

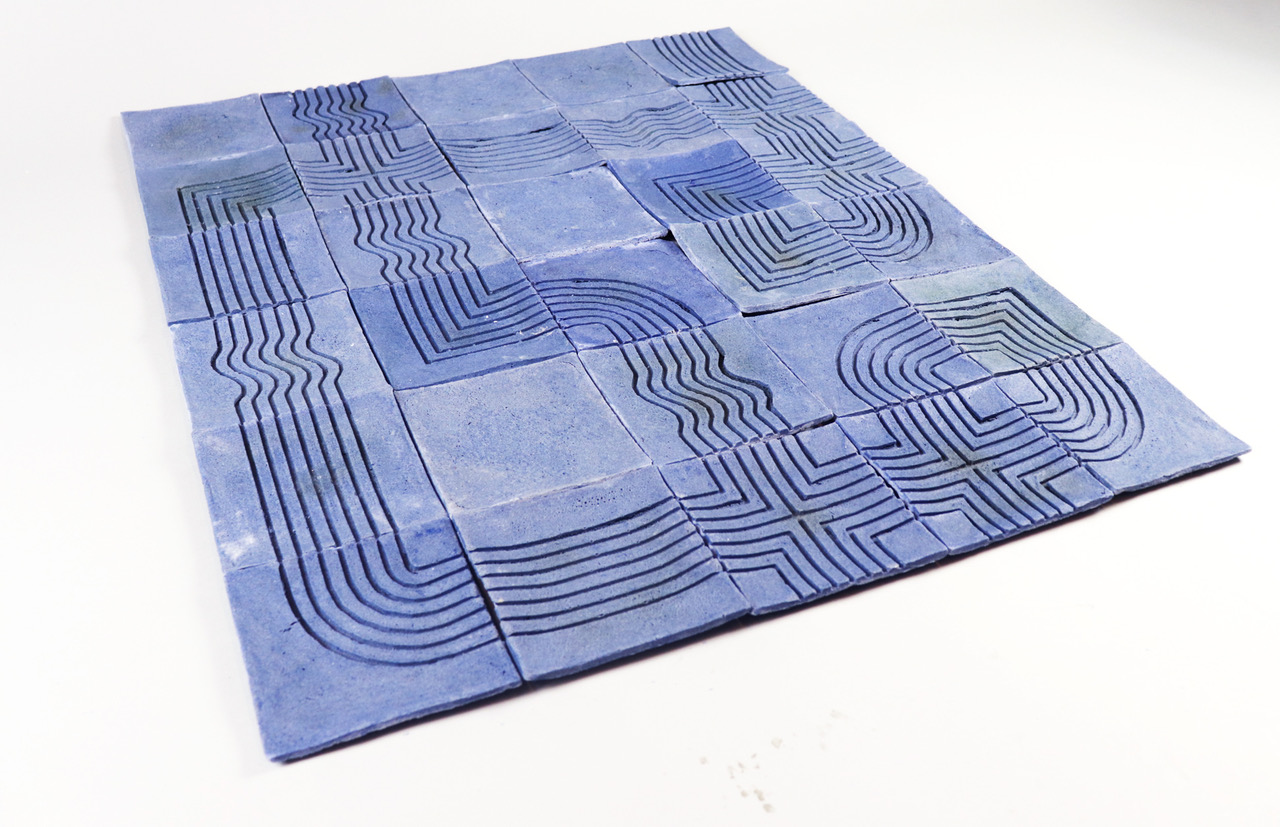

And across design disciplines, our students are thinking about how to radically reenvision materials—showcased beautifully in Pratt’s Material Lab—and they’re doing that by working with existing resources and natural methods to propose new approaches to packaging, textiles, building components with renewable lifecycles. They’re going on to develop those ideas in the world, producing materials like cactus leather, kelp yarn, and pigments made from sequestered carbon. They are consciously putting out options that resist environmental injury.

These are the kinds of trends that are touching all of our work. When we’re thinking about the future, it’s not about having to always start anew. It’s about accommodating transformation.

DH: On an organizational level, our core mission is always going to be our core mission, but structures can change, can shift, can flex, to allow us to respond to the moment we’re in and to lead in that moment. To do that, we’re going to have to keep working together. We need to keep looking at where we collaborate and why we collaborate.

I’m thinking about what we’re creating at the Brooklyn Navy Yard and the range of researchers that we’ll be bringing together there, from community-development activists to information-visualization leaders. Along with our designers and artists, having humanists, philosophers, and social scientists there would bring something to the mix too. We don’t tend to think about our research spaces in that way.

I’m thinking about the work our faculty members Chris Jensen and Mark Rosin from Math and Science and Heather Lewis from Art and Design Education are doing right now, funded by a grant from the National Science Foundation, to develop a program that explores the theory and practice of transdisciplinary teaching across STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) and art and design. Over the next two years, they will plan and implement a Faculty Learning Community with faculty from the Schools of Art, Design, Architecture, and Information, to support transdisciplinary teaching that paves the way for students to enter into the rapidly changing fields of art, design, and STEM.

Faculty and students from the School of Art, the School of Design, and the School of Architecture, along with Pratt Libraries, are involved in an ongoing interdisciplinary project to research, preserve, and publicly disseminate the history of activism between and beyond Pratt’s gates. That project, Preserving Activism, showcased some of their work in Myrtle Avenue storefronts last spring. I think we’re modeling cross-pollination and can keep pursuing opportunities for that.

We are a school that teaches art, design, architecture, information sciences, and we also bring strength in the liberal arts, and a commitment to reflective, deep critical thinking. That identity, that disciplinary richness, and the work fostered by that creative mix is part of what makes us an important locus for post-secondary education, and a voice in public conversations. We’ve literally shaped the world we live in, and we’ve done it with all the tools and consciousness that come from those habits of critical thinking, synthesis, analysis that are so essential to meaningful work, that are part and parcel of our capacity for original research, whatever form that takes—research in the liberal arts and sciences, research that manifests as creative inquiry, that produces sculpture and painting and interior spaces and the built environment, all of it.

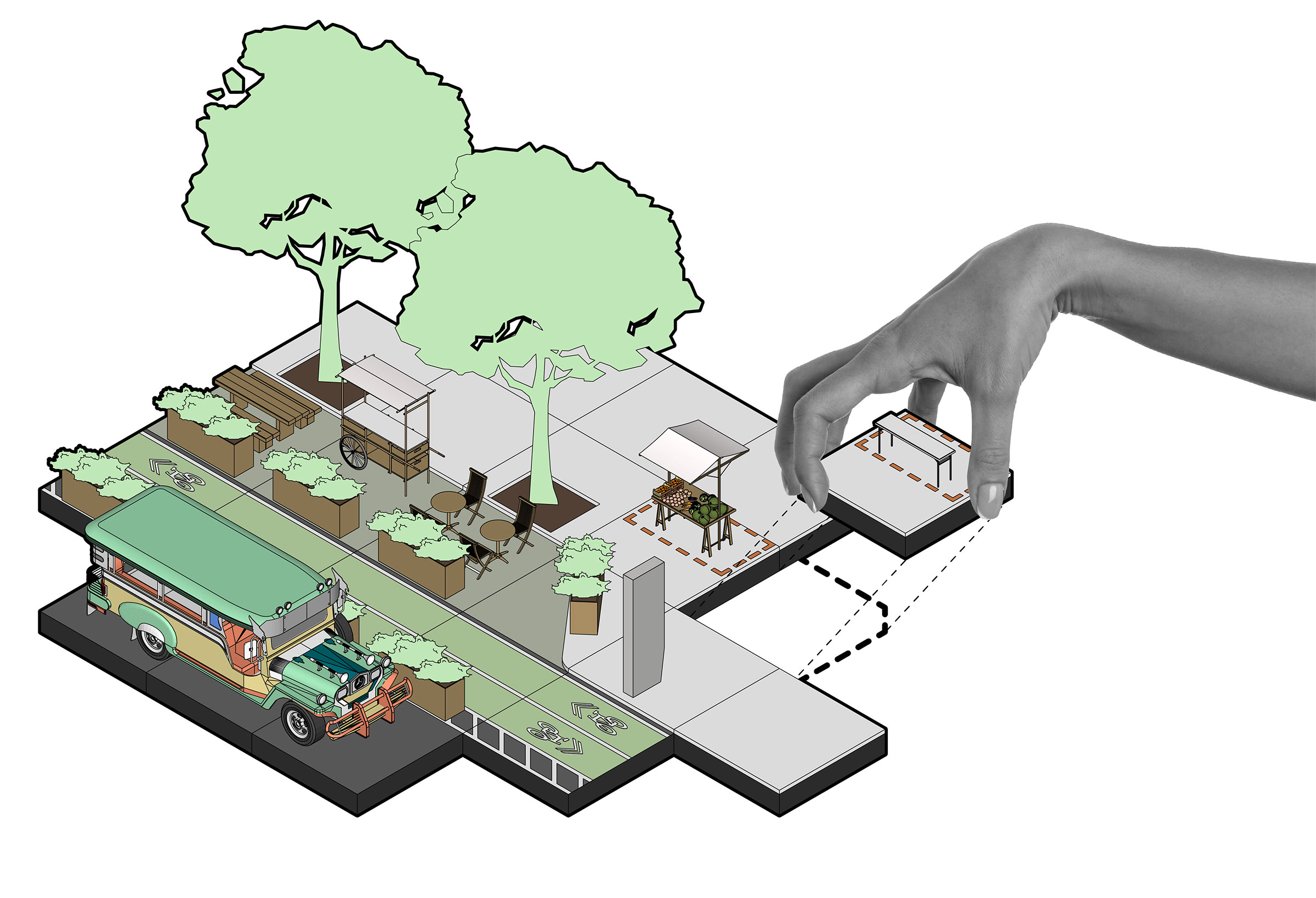

FB: Our graduates are immediately ready to make a difference in the world, and while they are here, many of their proposals are based on authentic projects. They’re doing art installations in the community. They’re rethinking transportation for Wallabout. They’re looking at the carrying capacity of Governors Island. They have real data, real information, real research. Faculty who are deeply engaged in civic work are helping our students understand the social and political landscape in which their work will take its place, and also how their work can change that landscape.

DH: Our Fine Arts Civic Engagement Fellow, this year, artist Mary Mattingly, is engaging BFA and MFA students in work around environmental justice and the climate crisis. In the School of Liberal Arts and Sciences (SLAS), Writer in Residence Aracelis Girmay, who has served as assistant chair of writing, has a new hybrid faculty position that involves both teaching in the undergraduate and graduate programs and advancing Pratt’s commitment to civic engagement through a course or programs within SLAS. In her new role as Assistant Professor of Community Engaged Learning for the School of Design (SoD), Irina Schneid is developing interdisciplinary community-partnered courses including Interplay: Ethics and Tactics of Co-Design and the SoD Co-Design Studio.

FB: So when they leave, our graduates see that their work is part of a larger ecosystem.

DH: Going back to what you mentioned earlier, our work as educators is also part of that ecosystem, and the way we teach at Pratt can reverberate beyond our campus. When I first came to Pratt, I noticed something that I’d also noticed at my last institution, which had a focus on creative arts but was not an independent art and design school: we were doing astonishingly powerful work in what I thought of as fairly progressive pedagogical practices. There’s a lot of very engaged hands-on learning that is at the same time very deeply reflective, very mindful, very richly conceived. This is a model that I think others can learn from. Institutions strive to recreate this, and they have to work hard at it. I think we have a lot to bring to conversations on the national higher ed stage, so I am focused on supporting faculty as they take part in those conversations.

FB: I think there are also opportunities for us to find partners and co-present on issues our work engages—for example, with politicians and economists on the making of a city. To passionately take our voice into the world. We need to have it on a 20-year plan, that this is going to be on the national agenda—for people to understand why connecting with creative artists and designers opens up ways of perceiving and acting, to take advantage of large opportunities to problem solve, to seek answers that sit within the very projects that our faculty, our students, alumni are working on.

Imagine if people who were projecting the future would have approached it from a more deeply community-engaged design perspective. We would have imagined how complex transit systems, including public transportation and highways, could have created equitable access. We would have thought about the internet differently. Design is an integrated condition. And that’s where our opportunities are, pulling teams together with expert knowledge, with local knowledge. That’s what we do.

DH: I’m watching a tour group go by—that is our future.