Marilyn Nance’s bags were packed. A Canonet, a Miranda Sensomat, film for 1,500 frames. A T-shirt screen printed “Okra Is an African Word,” a design collaboration with a friend. A letter declaring “You’re here as a photo technician,” the ticket to press credentials on site.

Twenty-three years old and just months past her graduation from Pratt Institute, Nance was fully equipped for a life-changing project when she prepared to board a flight to Lagos, Nigeria, in January 1977.

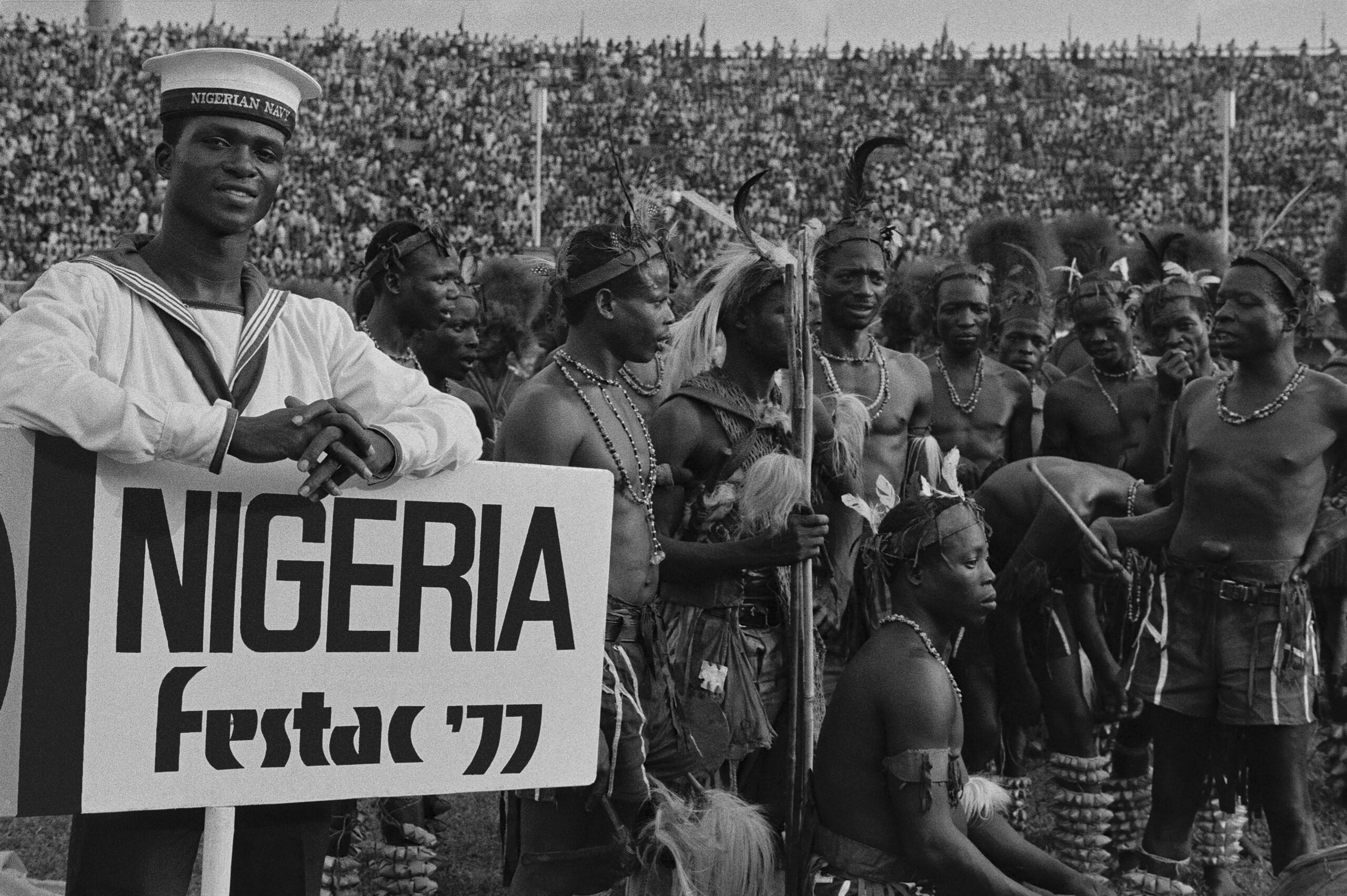

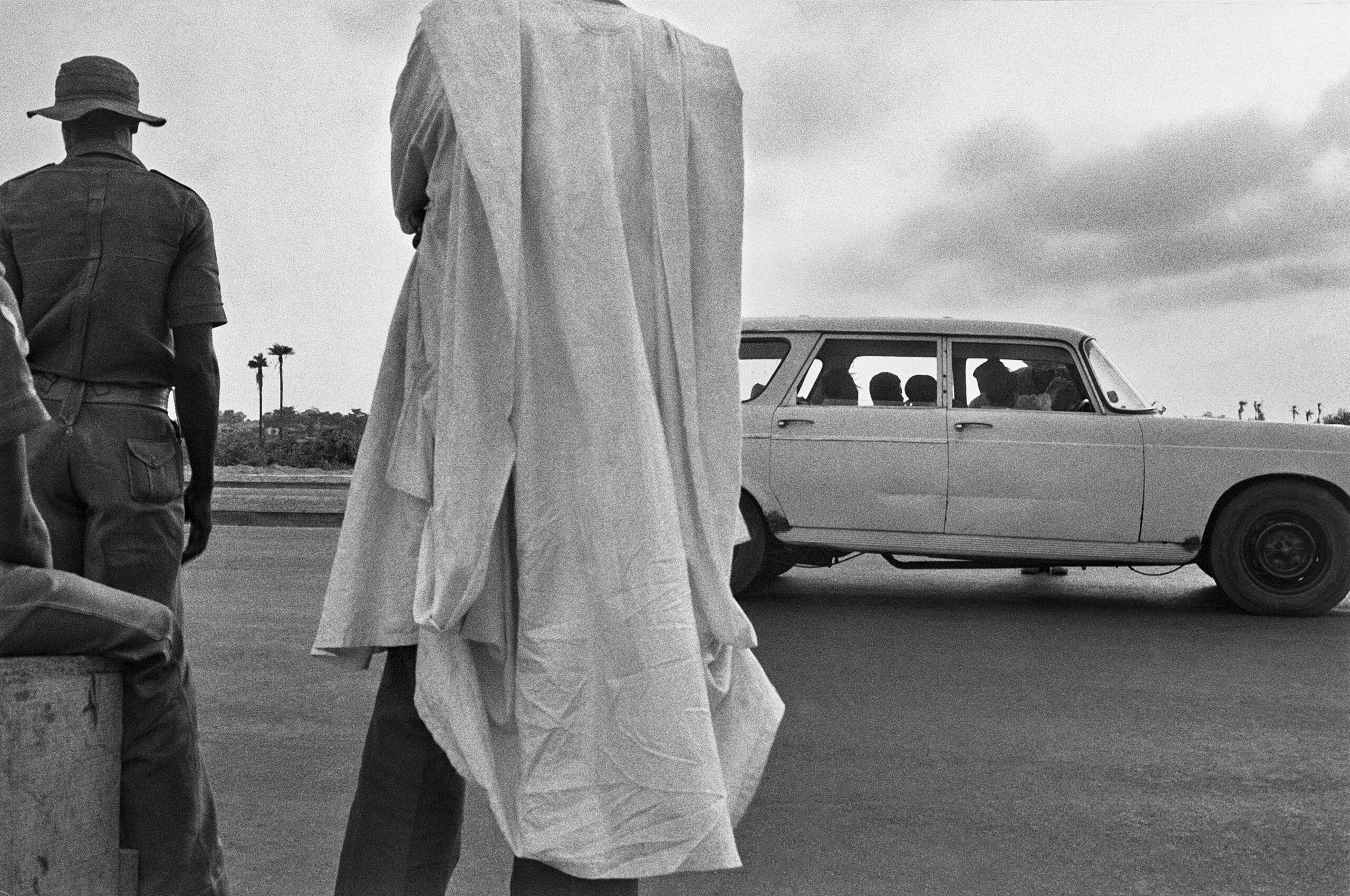

She was bound for a highly anticipated international gathering with captivating ambitions—to gather a world of Black and African culture in one place for four weeks. Years in the making, the Second World Black and African Festival of Arts and Culture, known as FESTAC ’77, would commence on January 15, 1977, attracting participants from 54 African countries and the diaspora. She would serve as the North American Zone’s official photographer.

While back home, American audiences were immersed in the landmark lineage-spanning television event that was Roots, Nance and her fellow travelers were participating in an experience that Nance likens to “an African Olympics/Biennial/Woodstock.” FESTAC ’77 reflected a kaleidoscope of origin stories linked by ancestry and the effects of colonialism, enslavement, and inequity, meshed with dreams for the future and the flourishing of the Pan-African spirit.

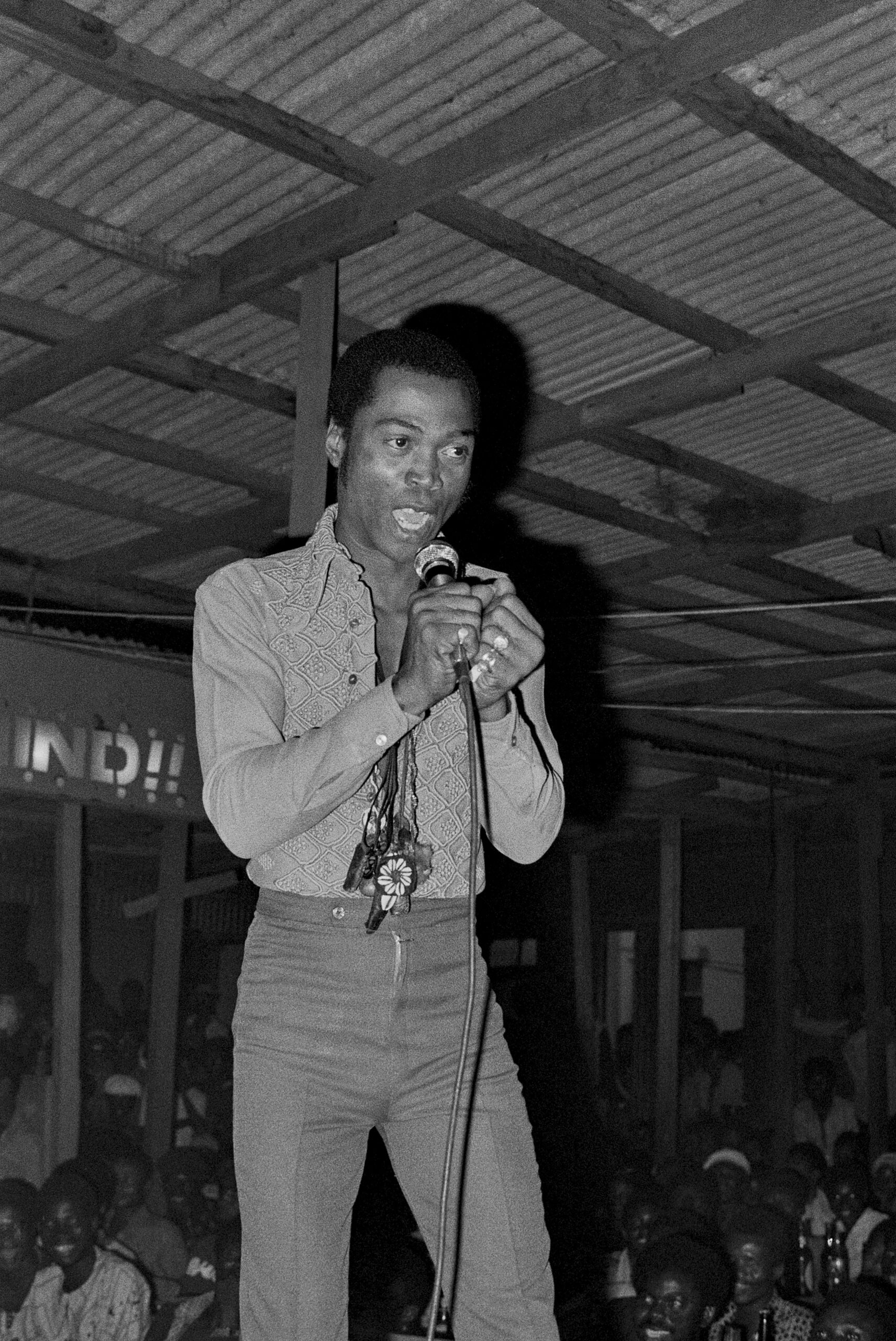

Some 17,000 writers, artists, musicians, intellectuals, and other creators of culture were present, and the shape and complexity of what happened on those 29 days would later be revealed in their work—like Jayne Cortez’s poem “Firespitters (FESTAC 77),” Audre Lorde’s poem “Sahara,” and Wole Soyinka’s essay “Festac Agonistes.”

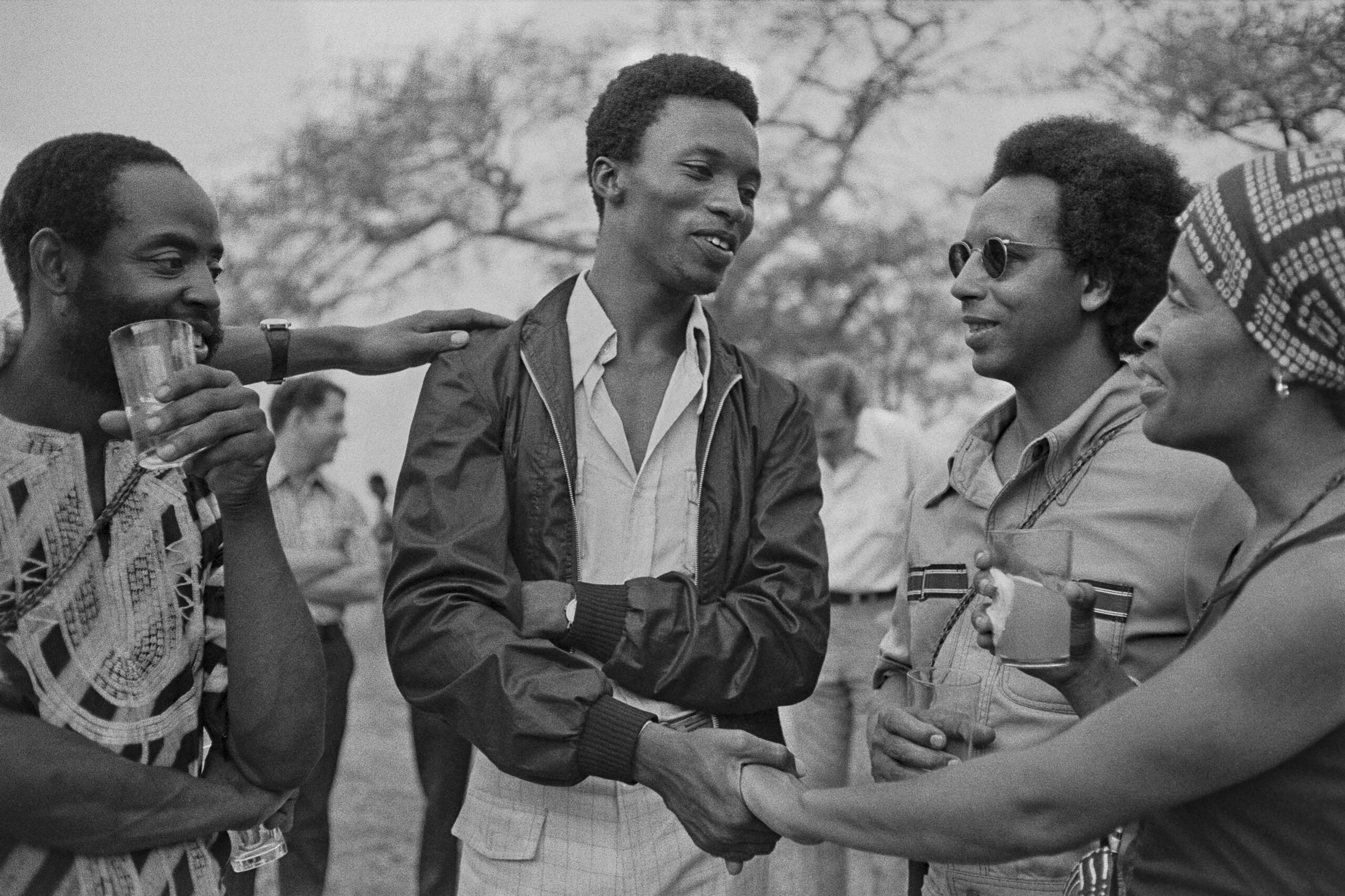

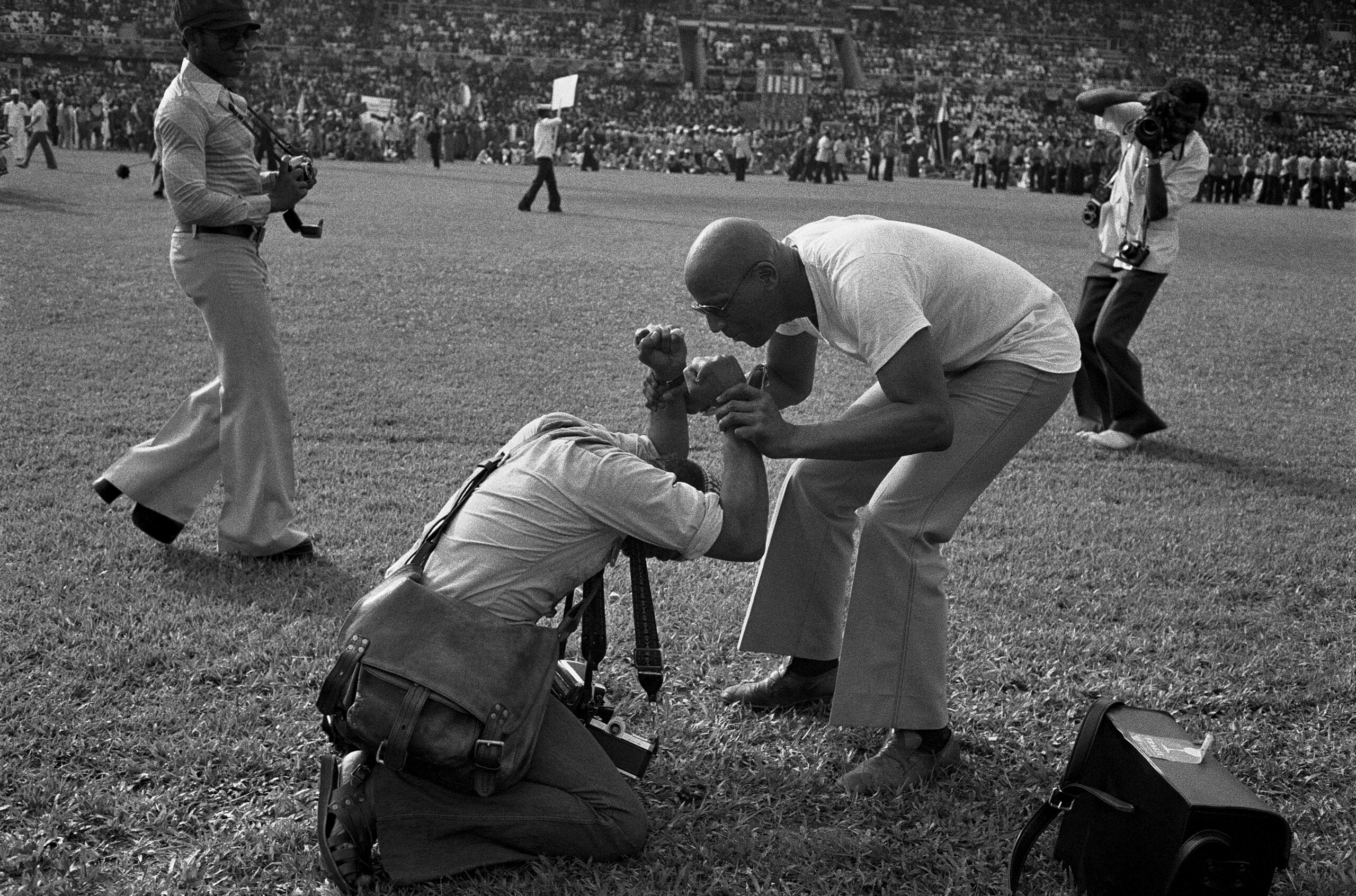

Alongside them, Nance’s photographs would become an unparalleled visual record of this sprawling, complex event—spanning dazzling stadium-scale pageantry and behind-the-scenes preparations, luminous performances and intimate exchanges, under the auspices of the official event and offsite.

Nance’s book, Last Day in Lagos, published last fall by Fourthwall Books/CARA, for the first time presents a collection of those images, selected from the 1,500 Nance made at the event.

“From the inside, she rendered the Black radical imaginary of an incredibly ambitious, international, Afro-futurist, diasporic Pan-African arts and culture festival.”

Julie Mehretu

Originally slated for a two-week stay in Lagos, Nance skipped the first contingent’s flight home and photographed the full festival and beyond, over the course of five weeks. Moving through FESTAC village and around the region, guided by a list of each day’s happenings and her own curiosity and intuition, Nance captured the lived experience of FESTAC, its jubilant ceremonies, artistic expression, people connections, inner workings, and roving movement from the proximity of a fellow participant.

Her direction didn’t come from an assignment or journalistic objective, but something more instinctive, and deeply felt. “For me, FESTAC was this site of mutual fascination. Everybody was fascinated with everybody else. Everyone participated. So for me, it was all about imaging joy,” Nance told Oluremi C. Onabanjo, editor of Last Day in Lagos, in an interview published in the book.

The images serve as more than documentation, rather a portal to the specific vibrations of this moment in time.

“She has created something true and important that goes way beyond the bounds of photojournalism,” artist Julie Mehretu says of Nance in her foreword to the book. “From the inside, she rendered the Black radical imaginary of an incredibly ambitious, international, Afro-futurist, diasporic Pan-African arts and culture festival.”

Nance arrived at FESTAC with another Pratt alumna and dear friend, Sharon “Ajuba” Douglas, BID ’75 (1953–1996), to whom Nance dedicated Last Day in Lagos. Their journey might have never happened had it not been for Nance’s persistence, and perceptiveness.

Years earlier, both had been accepted to the North American contingent as exhibiting artists. Nance’s submission was a photograph of her grandmother at a kitchen table, and Douglas was to show a font, Grafikan Systems, that she had designed. As festival plans changed—from the time Nance applied in 1974, the festival, once slated for 1975, had a series of postponements in response to political events in Nigeria and the pace of preparations—so did the size of the contingent, and Nance and Douglas both received word that they were cut from the list. But Nance discovered a side door.

“I was at the Institute of New Cinema Artists, and I heard two of the instructors, two male instructors—I eavesdropped—talk about how FESTAC was looking for technicians,” she told fellow alumna Jelani Bandele, alumni engagement manager for The Black Alumni of Pratt, in an interview for Prattfolio on the Brooklyn campus last December. “So Ajuba and I reapplied. Both of us were supposed to be exhibitors, and we reapplied as technicians. We didn’t take no for an answer,” and, she added, “whatever I wanted for me, I was like, Ajuba, come on!”

When Nance and Douglas traveled to FESTAC, it was a new chapter in an alliance cemented at Pratt, over hours of working side by side, sharing time on Pratt’s in-demand Photostat machine and working side by side in friends’ apartments. They collaborated on a series of T-shirts that they sold at the African Street Festival on Claver Place in Bed-Stuy. (That series included the shirt reading “Okra Is an African Word” that Nance would bring to Lagos.) And they had fun.

Their creative and sisterly bond came with the usual share of dramas but was magnetic above all. “We used to fuss and fight,” Nance remembered, laughing. “I said, when I get to Africa, I’m not staying with you—and we wound up in one place.”

And there they are back in the States, in a 1978 photo by Dawoud Bey, selling postcards Nance made from one of her FESTAC photos at the Third Annual Lewis H. Michaux Book Fair at The Studio Museum in Harlem.

It’s relationships like this that Nance encourages students to nourish: “It’s really important when you’re in school to work with your friends.”

That connective potential is what first drew Nance to Pratt. Before enrolling as a student, she knew the Institute from gatherings and performances held on and around the Brooklyn campus. Having grown up in the Farragut Houses, a little more than a mile and a half from Pratt on the western border of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, during her high school years, the campus was a social and cultural hub.

“Pratt was known for having community events,” she said, recalling one particularly epic three-day jazz festival put on at Higgins Hall, organized in part by Ogundipe Fayomi, BFA Sculpture ’73, that featured, among others, Alice Coltrane playing the harp.

“I felt included, I felt like I was a part of it,” she said. “I came to Pratt knowing that history and being a part of that continuity of involvement with the community.”

Nance had come to Pratt Institute after studying for a year at New York University as a journalism major, finding she could move more fluidly among her interests in art and design at Pratt. She majored in graphic design after considering architecture but felt unhindered from exploring across fields, and she found her interdisciplinary mindset echoed among her peers.

“My first friend at Pratt, Patricia Miller [BS Environmental Science ’78; BCE ’79], started in painting, and she left in engineering,” Nance said, recalling also how Ajuba Douglas had started in graphic design (in fact, Douglas designed the logo for The Black Alumni of Pratt, still used today) and graduated in industrial design. “No matter what our training was, you could take it and pour it into anything else.”

To pursue her range of interests, alongside her design studies, Nance took part in University Without Walls, a Pratt program that facilitated independent study. Through the program, she took printmaking at The Studio Museum in Harlem with the artist Valerie Maynard, who would become a lifelong mentor, and joined a documentary photography course taught by Pratt professor Alan Newman, who would also have a significant influence on Nance’s direction as an artist.

It wasn’t Nance’s first foray into photography—a photo workshop at Farragut Houses Community Center had been her first instruction in the subject, and at Pratt, she had taken Photo 101 with David Freund—but Newman’s class and what came out of it would be transformational.

After having her in that course, Newman asked Nance to join a cohort of student photographers he oversaw in Pratt’s Public Relations Photo Studio. Nance recalled how she and peers like John Milisenda, BFA Integrative Studies ’75; Nina Prantis, BFA Photography ’76; and Lynn Saville photographed events, student work, graduations, public-relations moments like check signings, and campus construction like the building of the ARC.

“That’s where I became a photographer,” she said of the Photo Studio. “The thing that made me a photographer was the 24-hour access that I had in the Pratt Studios photo lab. I could come in there anytime and do my own work. Of course I did Pratt’s work too, but I had complete access—we all had complete access—to the facilities. My time at Pratt made me a photographer.”

It was more than hours in the lab, though, Nance continued. Newman’s approach in the Photo Studio also forever shaped her practice. “He was just . . . gracious,” she remembered. “He would tell me about other photographers—‘your work reminds me of this’—and so it was like a photo course, really.”

“I think my graphic design skill goes into the way in which I compose an image. . . . Some people just put their fingers on the shutter, but I can actually see the image that I want, and then I’ll wait for it to show up.”

Marilyn Nance

Nance considers Newman one of her mentors, though she didn’t realize the extent to which his early guidance had influenced her until some 40 years later, when she visited him at the National Gallery of Art, where he was overseeing digital media. “He introduced me to his staff, and he didn’t say, ‘This is Marilyn Nance. She used to work for me.’ He said, ‘We used to work together,’” Nance recalled.

Nance also credits Newman for having exposed her to the record-keeping practices she has come to be lauded for, and which enabled her work on Last Day in Lagos. Every contact sheet is named, numbered, and dated. Every image Nance has ever shot has a file number, and materials are organized in boxes whose locations are meticulously recorded on a spreadsheet. “It’s a system that I adopted based on my work at Pratt in the Pratt Institute Public Relations Photo Studio,” she said.

Nance’s photo practice grew from there, while she was still a student, and she began taking on work. “I thought, I have the skills, I can do this anywhere,” she recalled. “I was used to being published because I had been published at Pratt,” in Pratt Reports and Prattonia, the yearbook. In 1975, she started photographing for The Village Voice, under fellow Pratt alumni Gil Eisner and Sylvia Plachy, BFA Illustration ’65.

By the time Nance graduated from Pratt, she could have taken a number of paths. “I had studied art direction. I had studied copywriting. I had studied graphic design,” Nance said. She chose photography.

Nance’s design studies at Pratt have fed her practice. “I think my graphic design skill goes into the way in which I compose an image,” Nance reflected. “Some people just put their fingers on the shutter, but I can actually see the image that I want, and then I’ll wait for it to show up. You actually create the image by knowing in advance what’s going to happen, or feeling what’s going to happen, and then you just wait for it to happen. It’s almost like meditation.”

Her words of wisdom for those waiting behind the lens: “Just hang in there, because the photograph is not really what’s outside—it’s what’s in you that you’re expressing. What you want to happen is for someone to look at the photograph and feel the same way you felt when you made the photograph. It’s not about the event—I looked at my images [from FESTAC] and I have photographs of . . . nothing happening,” Nance said, laughing. “The stuff going on is in the head, or in the heart. If you’re waiting for somebody to do something, the somebody to do something is you.”

Even as she would go on to work in advertising and as an educator, Nance continued to build her body of photographic work, making images that capture the essence of Black life on a closely observed, human scale—work that is now in the collections of the Brooklyn Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the Library of Congress, and others.

Of late, Nance has been particularly invested in sharing her work with a younger audience, extending the continuum of knowledge and culture exchange that was central to the ethos of her time as an emerging artist, from her earliest participation in civil rights actions, to her involvement with fellow young artists and elders in the Black Arts Movement. This principle comes to bear in her lifelong project of making and showing images of the Black experience, what Nance has called “a giant family album.”

For Nance, communication among generations is critical to carrying creative work forward. “We had an information economy that was about sharing,” she said, recalling her time as a young artist. “I think it may be a little different now, but I’m a throwback, and I still share information, especially with young folks.”

Her biggest piece of advice for those coming up behind her: “Talk to old folks.”

Nance’s meticulous record keeping is a way of ensuring that information—friendships and connections, actions and events, moments in time—is preserved, and able to be found.

In 2014, Nance initiated the project of revisiting her work from FESTAC ’77. She worked with visual artist Valerie Caesar to digitize all of her contact sheets from FESTAC and make high-resolution files of the negatives, which Nance then used to make reference prints.

Her participation in cross-generational conversations was central to bringing those images to fresh light and Last Day in Lagos into being. In 2016, Nance was presenting her FESTAC images with Caesar and Valerie Maynard, coalescing three generations of mentorship, at the Black Portraiture[s] III conference in Johannesburg. It was there that she connected with curator and arts scholar Oluremi C. Onabanjo, who recognized the potential in the work immediately.

“Remi, I’m going to let you discover me,” Nance joked with Onabanjo, she told New Yorker writer Julian Lucas in an interview on The New Yorker Radio Hour earlier this year.

She would go on to work with Onabanjo as her editor and collaborator on Last Day in Lagos, resulting in a volume lush with imagery, history, critical observations, and bibliographic references—as Nance herself said, “It’s a textbook. It’s a testimonial. It’s an art book. It’s a photobook.” (It was shortlisted for the 2022 Aperture Photobook Awards for first photobook.)

It is a chronicle of just five weeks of the artist’s life that offers a window into the past, present, and future, her own and that of the collective.

Now, beyond the book, a more complete picture of FESTAC ’77 continues to unfold, through Nance’s diligence. In 2022, as part of the Magnum Foundation Counter Histories cohort, Nance began the FESTAC Memory Project, to collect names, narratives, and images that add new dimension to the story of FESTAC ’77, and to tell that story in different ways.

Building off her initial slideshow concept for the project, for example, Nance commissioned Caesar to produce five short films with images from the festival. This year, with the support of the New York State Council on the Arts, Nance will continue to develop the project in the public realm.

All of this work has been 45 years in the making. Why hadn’t the world taken an interest years ago? In the interview with Lucas, Nance redirects the question to the historians, the publishers, the cultural gatekeepers.

“I guess there was no investment in celebrating Black joy,” Nance remarked. “I had to wait until a new generation came.”