Community, diversity, accessibility, serendipity.

As we emerge from our isolation, and New York City reawakens, designers, architects, and urbanites who live in and love this town have an opportunity to investigate and rediscover what truly makes this city what it is. How can we reimagine the built environment to mitigate disparity, cultivate connectivity, and support not just a surviving but thriving metropolis in our new post-pandemic world?

Let’s meet a few recent Pratt architecture and interior design graduates who have approached their work from this perspective. In unique ways, each project aims to reimagine and redefine the built environment of New York, designing within the constraints of the city’s long-established urban framework. These projects speak to the opportunities of this historical moment, proposing ideas and designs for a city on the precipice of a new paradigm, where communities flourish through hybrid environments, shared resources, and collective care.

Financial District

Chris Brown, BArch ’21

Formerly, One Chase Manhattan Plaza

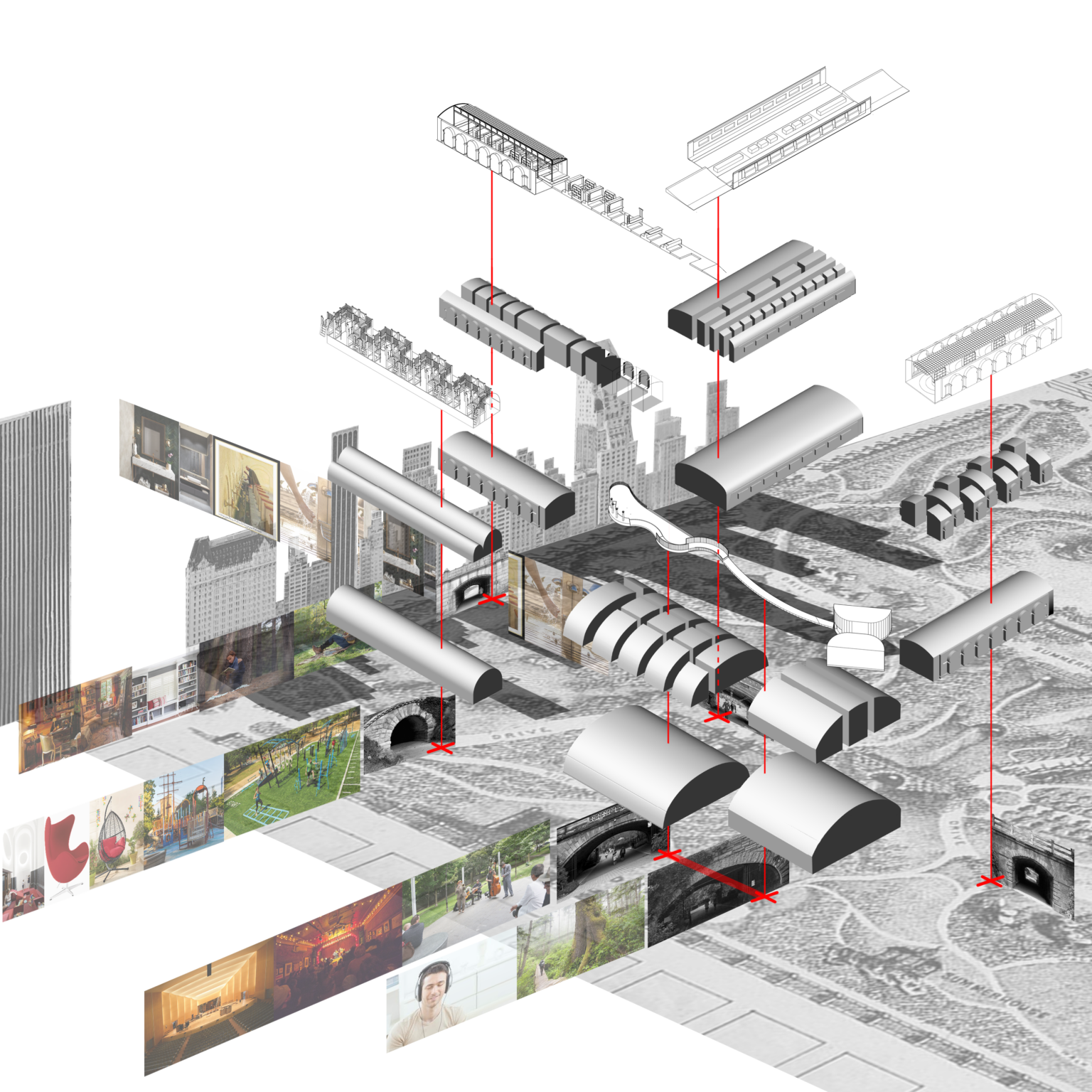

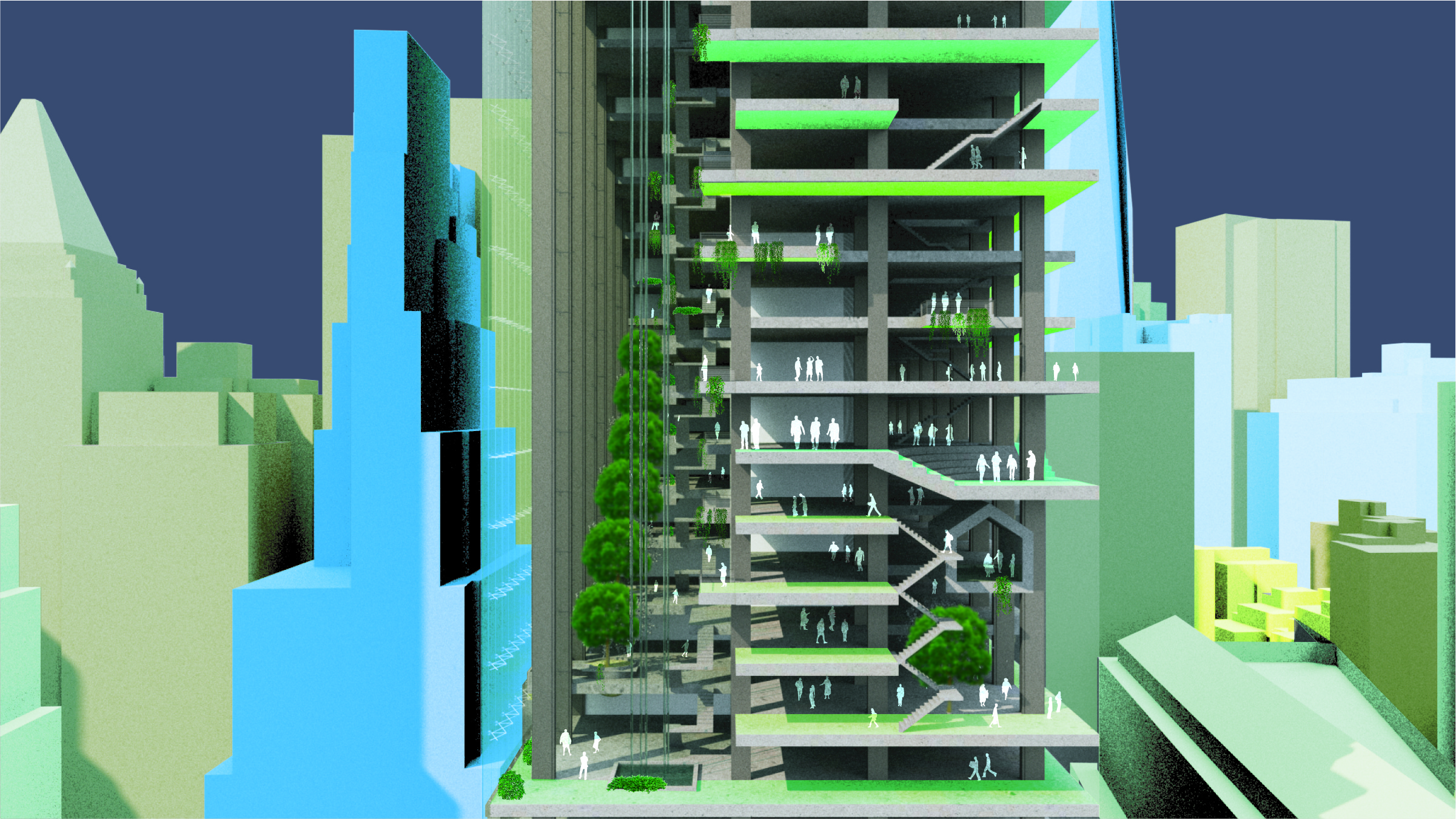

For Chris Brown, our post-pandemic world is an opportunity to reuse and reinvigorate New York City’s modernist towers. With his thesis project, he reimagines 28 Liberty Street, formerly known as One Chase Manhattan Plaza—a 60-story, 60-year-old International style skyscraper in Manhattan’s Financial District.

“The pandemic revealed a structural weakness of Manhattan,” Brown explains. “Prime office real estate sat empty for years. The pandemic has only exacerbated this situation.”

-

![Pulled-back side view of skyscraper showing zig-zag pattern of enclosed and open spaces, colored yellow, green, and blue]()

Office space is recast as an integrated mix of space for residential (yellow), education (blue), and mixed (green) use.

-

![Three drawings of a skyscraper complex color-coded for residential, mechanical, green, retail, and office space, labeled “the past,” “the present,” and “the future,” where past and present have stacks of different colors and future has a woven pattern]()

Brown’s proposal calls for a reexamination of work-life balance, recentering people and communities through a more inclusive model of occupying a building.

-

![Overhead view looking down the side of a skyscraper colored in shades of red, green, and yellow to represent the types of occupant use]()

Terraces of public green space scale the facade of Brown’s reimagined office tower.

Brown’s redesign of this iconic tower aims to inspire a new typology of skyscrapers in the city with what he calls “a radical recentering of community.” As we all work to adapt to our new lives—at home, at work, at third spaces—Brown envisions a truly multi-use space to support the new way we live in a city like New York.

Moving away from the introspective, autonomous nature of towering office buildings, Brown injects a holistic usage from ground level to the rooftop with a mix of residential space—for families, individuals, and students—as well as office space, retail, and public space. Furthermore, 20 percent of the building is dedicated to an educational complex for both residents and commuting students, and Brown proposes slicing open the facade, creating glassed-in wedges of “winter gardens,” to utilize 10 percent of the building as dedicated green space.

“The renewal of a modernist tower is an example of the possibilities of the future, reconciling our post-pandemic urban density,” Brown says. “What we expect from our architecture must change. Why return to a city built on privatization and self-isolation when there is an opportunity to develop a remarkable, equitable, and empathic city for the future?”

Lower East Side

Kelli McGrath, BFA Interior Design ’21

The Tool Shed

“In this time of societal rebuilding, designing with care is at the heart of how we can grow and connect with one another,” says Kelli McGrath, BFA Interior Design ’21. “By designing with care, we are truly thinking about who we are designing for, and how to make their lives better by providing them with spaces that they can enjoy themselves in, have chance encounters with each other, share and learn from one another.”

These ideas were the basis for McGrath’s project The Tool Shed, a proposed community center for the existing Stanton Building at Sara D. Roosevelt Park in Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

“The Tool Shed’s design nurtures and supports the diverse community around the center by providing the ‘tools’ and resources [residents] need,” McGrath says.

These tools include actual construction power tools and hardware that community members may not typically have stored in their homes. But McGrath also imagines a broader suite of “tools” for sharing—from computers and charging stations, to a library, maker space, tutoring rooms, give-take boxes, recreation kits, and on-hand subject matter experts.

-

![Overhead view of a community center between Chrystie and Forsyth Streets, showing a green roof where people practice yoga, brick patios labeled “serendipity zones,” and square chair-and-table sets around the periphery]()

Interior design extends to the exterior with the inclusion of a green roof and skylights that distribute sunlight throughout the building.

-

![Washers and nuts are suspended along the rails of a metal staircase, with a brick wall in the background]()

The skill-sharing concept of The Tool Shed includes inviting community members to cocreate elements of the space like this stair rail made with upcycled washers and nuts.

-

![The bustling exterior of a community center showing children playing, bicycling and skateboarding, people in wheelchairs and on foot moving through the patio, and a group congregating in a circle]()

Outdoor resources such as give-take boxes and “serendipity zones” on the patio activate the areas surrounding the building.

“The intention is for the Stanton Building to provide for those various needs through the process of sharing and exchanging resources, knowledge, and advice,” McGrath says, envisioning the center as a space to access resources and also work together for collective benefit.

One of the central components of the center is a reuse-and-recycle program that also informs the design of the facility itself, where community members can add both practical and artistic details to the physical space. “For example, classes can have community members bring old nuts and washers to make a guardrail post that will become part of the building’s stair guardrail,” McGrath explains. The would-be discarded objects that visitors bring to the site would mingle to create “a fun mosaic within the building that is reflective of the diverse community, apparent in the different styles, colors, and wear of the materials.”

The enjoyment of collaboration and design, especially as the city emerges from the isolation of the pandemic, could have a ripple effect. “Design can prompt larger questions about social justice,” McGrath says, “and I believe that by designing thoughtful spaces, we can set an example for a better future where we all feel at home anywhere we are in the world.”

Central Park

Tao Sun, MFA Interior Design ’21

Inhabiting In-Between Space

“Would you like to sit inside-inside, outside-inside, or outside-outside?” a restaurant host asks a pair of would-be diners in a New Yorker cartoon by Jeremy Nguyen, published in May and referenced in a thesis presentation by Tao Sun, MFA Interior Design ’21. Sun addresses the question of interiors and exteriors and the nuanced range between these two formerly binary worlds in his thesis, Inhabiting the In-Between Space.

“During this tough time,” Sun says, “parks, community gardens, and waterfront playgrounds have proved themselves to be better social spaces than coffee shops and bars. And they can do more with the help of interior design.”

Sun considered the idea of a “minimal new interiority” that helped people feel safe coming together during the pandemic, and how design for this in-between spatial experience could create “a harmonious atmosphere, even if it is not seriously interior space.”

-

![In an arched stone passageway, people sit on wood benches and look through books from shelves built into the walls, as a walker strolls past on a gray-tiled section of the tunnel]()

A free library concept for Central Park’s Dipway Arch, part of Sun’s project to rethink liminal spaces in the park.

-

![Diagram showing the space within a selection of Central Park’s tunnels and the interior architectural components to fill that void]()

Sun sited the project within five of Central Park’s tunnels, Denesmouth Arch, Dipway Arch, Driprock Arch, Inscope Arch, and Willowdell Arch.

-

![People pass through a park tunnel with wall and overhead bricks tinted in a pale green-blue, with a long red ceiling fixture; green, white, and red concentric circles on the floor; and a row of bookshelves running the length of the tunnel]()

Within Willowdell Arch, Sun imagines a colorful portal to bridge interior and exterior space.

Sun’s thesis project reimagines the tunnels and archways of Central Park as curious, communal spaces, aiming to establish what he calls “a new type of social engagement.”

Originally drawn to Central Park for its wide appeal and accessibility — for both New Yorkers and visitors alike — Sun’s approach is meant to further democratize the public space.

“No doubt these arches are shelters when it is raining, gates to the next area, and in-between space between nature and manmade structures,” he says. “But with proper furnishings, they can be a new type of interior, not strongly influenced by the weather and not limited to just pathways.”

Keeping with the archway walls and exterior facades, Sun has designed a series of welcoming open-air spaces within the tunnels: libraries, rest areas, and water stations that extend beyond the reach of the archways. They invite visitors to read, listen, pause, discover, and play by gently guiding them from an outside-outside environment to an inside-outside environment within the tunnel.

“To me, they are just like the rabbit hole in Alice in Wonderland,” Sun says. “They are thresholds between different worlds.”

Sunset Park

Crystal Chen and Suvian Tan, BArch ’21

Inter-gen Living: Bridging Cultures

“Sunset Park is a neighborhood facing very real issues of residential overcrowding, displacement, and gentrification,” say Crystal Chen and Suvian Tan, both BArch ’21. “Because of the stagnant housing stock of low-rise row houses in Sunset Park, the neighborhood faces a serious overcrowding issue followed by risks of health and safety when residents turn to illegal conversions as means to share the burden of rent and increase housing density beyond the zoned density.”

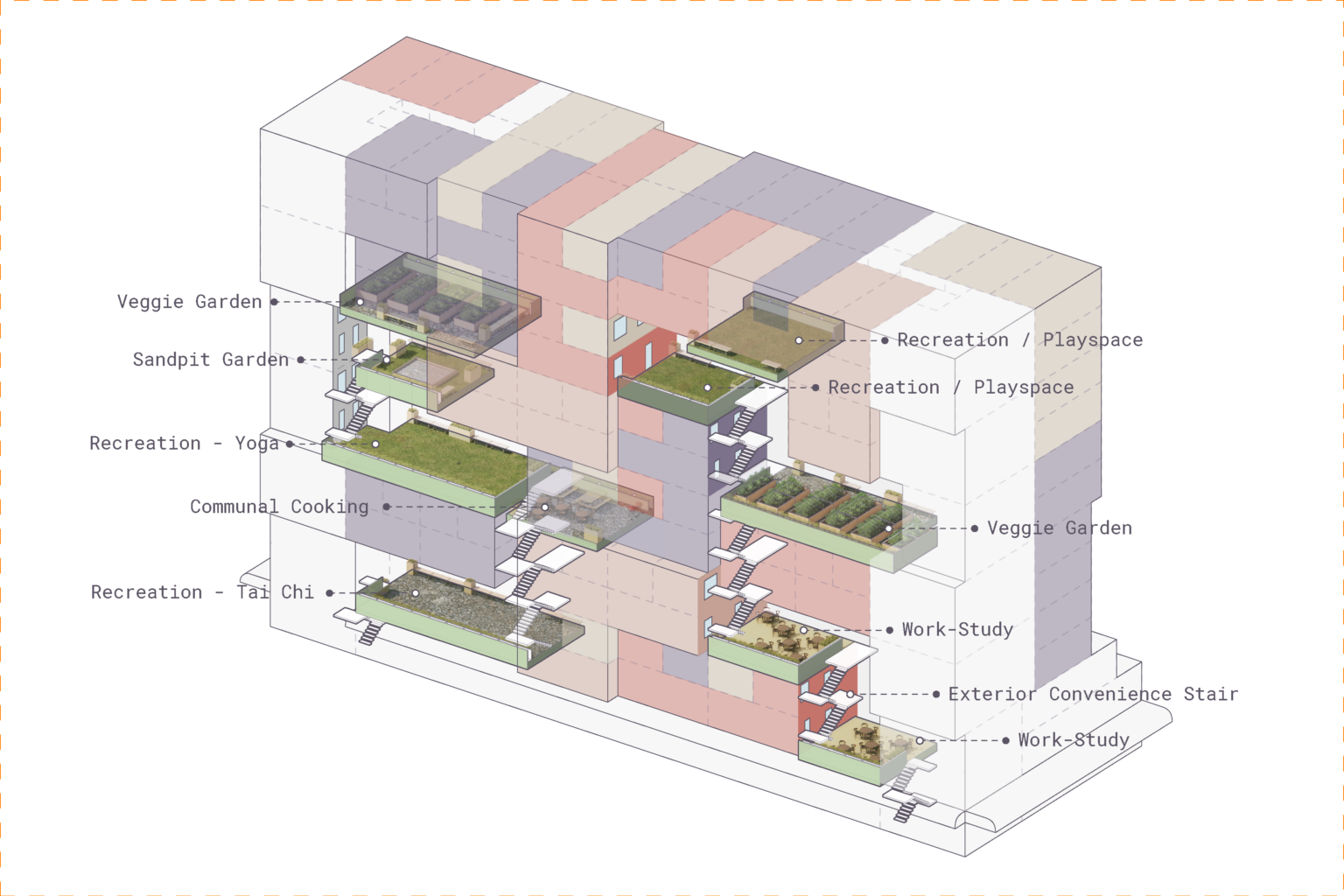

With their project, Inter-gen Living: Bridging Cultures, Chen and Tan aim to establish a new paradigm of housing collectives, a “revival of the village spirit and family hearth,” built around markets, coproduction, and collective growth. “Our design tries to nurture the important extended-family bonds that are shared among Sunset Park’s different ethnic groups and also bridge people from different cultures and age groups,” they say.

-

![Axonometric view of shared spaces within a city-block apartment complex, labeled recreation for tai chi and yoga, veggie gardens, sandpit garden, work-study, exterior convenience stair, and recreation/playspace]()

Shared spaces like vegetable gardens, communal cooking areas, and recreational areas are woven throughout a residential block.

-

![Adults and children walk in a courtyard surrounded by four-story residential buildings]()

An ample courtyard offers a flexible zone for play, rest, and congregation at the heart of the block.

Their “community-within-a-block” prototype consists of a nearly 1,000-resident city block of multi-family townhouses with existing backyards converted to a large, shared courtyard, bookended by communal buildings housing recreational facilities, on-site health care, social services, and additional support spaces.

“In our attempt to bridge and establish protection for these cultural communities, our design builds a sense of collective spirit among the residents across multiple scales,” Chen and Tan say. “The future of the city lies in the people, so it is important when designing the built environment to give great care and sensitivity to the needs and existing dynamics of communities.”

Brooklyn Navy Yard

Valeria Cedillos and Victoria Tsukerman, MS Architecture and Urban Design ’20

Brooklyn Plastic Hybrid

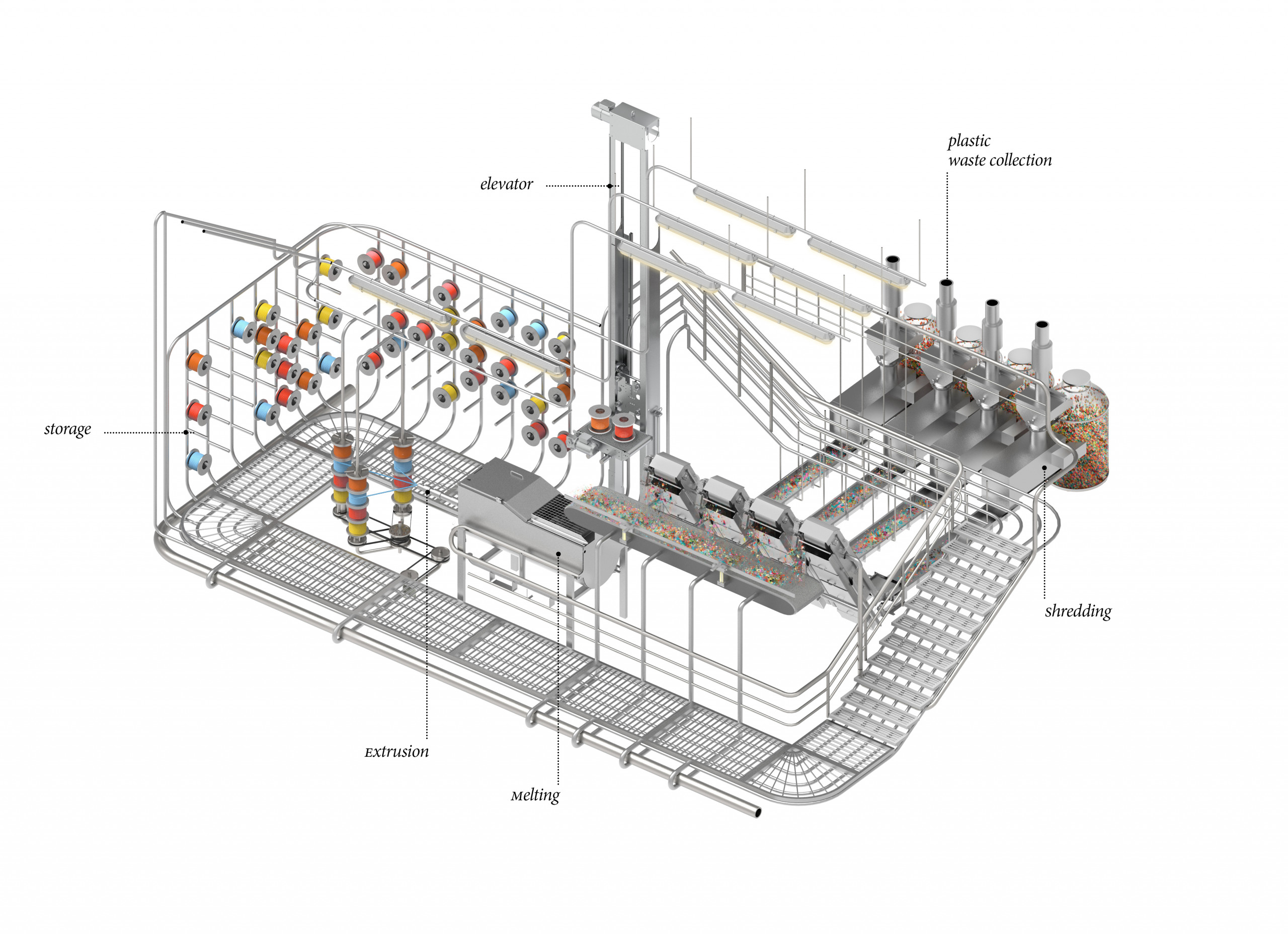

The United States generates more plastic waste than any other country in the world—producing 42 million metric tons, or 286 pounds per person. And the amount that gets recycled amounts to a fraction (according to a recent study, less than 10 percent of plastic waste in the US was collected for recycling in 2016). Taking on this aspect of our ecological crisis, and aiming to encourage urban community participation and civic engagement, Valeria Cedillos and Victoria Tsukerman, MS Architecture and Urban Design ’20, proposed a civic initiative that integrates public space with an environmental consciousness through plastic recycling.

“Instead of creating a project that tears everything down and starts from scratch,” they say, “we decided this was a perfect opportunity to create a model of how existing conditions can be redesigned and densified while maintaining historical value.”

-

![Cutaway view of a building from the back side, showing two levels with apartment furnishings, a ground-floor cafe with a counter and small round tables, and a basement workshop with a system of pipes and other machinery]()

A basement workshop along the block would become the site of a plastic-recycling operation, to produce colorful tiles for the street plaza surface.

-

![Diagram for a system of tubes and spools that shows how plastic could be shredded, melted, extruded, and stored as part of a recycling process]()

Cedillos and Tsukerman designed a plastic processing system to break down, melt, extrude, and store material.

-

![People and a dog sit, bike, walk, and play outdoors among wavy interlocking planters and benches]()

Recycled plastic components could be stacked to form benches, planters, and other street-plaza features that invite people to interact and play.

Their project focused on locations near the Brooklyn Navy Yard, about one mile from Pratt Institute’s Brooklyn campus, and the designers ultimately chose a site on a less dense block of Washington Avenue. In their model, a swath of the street would be reinvigorated as a vehicle-free public plaza, with a surface of multicolored tiles, aiming to activate urban life and attract visitors both with the vibrancy of the space itself and the context behind its creation.

In this model, residents would be engaged in the block’s development. The colorful tiles of the streetscape would be made of plastic recycled onsite, in basement areas reprogrammed as small-scale manufacturing spaces, with neighbors as participants in the industrial process and ultimately the reimagining of public space.

“As designers,” say Cedillos and Tsukerman, “we have to delicately think of interventions within the built environment since they impact everything within and around them socially and environmentally. The time has come to achieve a new level of consciousness prior to acting and proposing, in order to have a positive and long-lasting impact in our cities.”