“Home is the place where we most intimately meet ourselves, and can build a space where the primary concern is love, and care.” Madeline McQuillan, BFA Photography ’23, shared these words in a Q&A with Prattfolio for the digital edition of our Housing/Home issue. She and four fellow graduates of the photography program at Pratt Institute shed light on their recent projects that consider, from unique vantages, the ways we understand our dwelling places and our stories.

Absence and Presence, Loss and Possibility

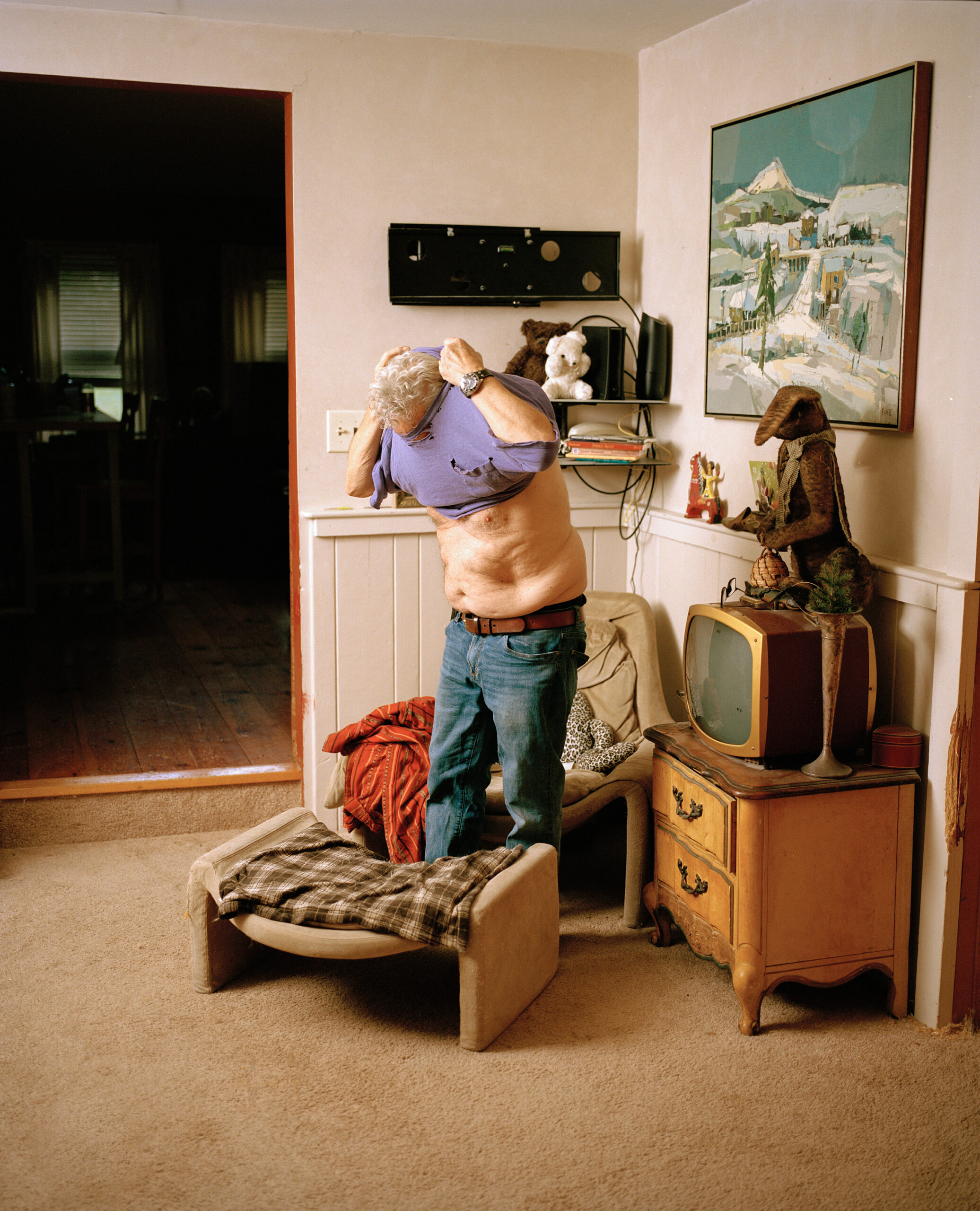

With her series Larry and I, Eliza McKenna, MFA Photography ’23, navigates grief and healing through image making in the most personal of environments.

What is the significance of home for you in your work?

The home is the backdrop for all of my pictures in this series [Larry and I]. Although Larry, the man in my photographs, is a man I met on the internet, the act of staging photographs in each other’s homes draws attention to the constructed nature of our relationship in the chaos of our realities. Larry came to represent a surrogate father of sorts after losing my own father to COVID-19, and bringing him into my own home allowed me to reenact events in an attempt to work through feelings of grief and loss. The home is charged with emotion and memory and the act of placing Larry in this environment reveals the emotional load that an environment carries after losing a loved one.

What are some sensations or ideas that define home—what do you imagine when you envision home—and how do those feelings or concepts relate to Larry and I?

While love comes to mind when I think about home, the suffering that my own father endured at the end of his life is also infused in my experience of home. Larry and I photographed all over the home and in specific spots that have memories attached to them in an attempt to rewrite feelings surrounding traumatic events.

Can you speak about a work of yours, or by another artist, related to home that revealed something to you?

In Larry Trying on Dad’s Shirt, the idea that objects and environments carry an emotional cathexis became immediately apparent. A shirt that my father wore to shreds is thrown over Larry’s body, and my feelings toward his presence in my life become one with my desire to see my father alive again. The home is imbued with irrational wishes and memories, and the act of staging Larry within this environment coupled with my father’s shirt allows for a sort of mental catharsis in the healing process.

How have your perceptions of home changed over time?

While my work with Larry is incomplete, the home has transformed from a place of memory to a place of possibility for imagining new realities.

Today, I feel as if my initial endeavor to feel a sense of relief in reimagining the life of my father is incomplete and needs to be explored in continuing to experiment with Larry. Although this unfinished feeling remains, the entire process has helped me work through the endless mourning process after a traumatizing death.

Photographing within the home has proved to be a valuable outlet for the inner workings of my mind and I aim to continue Larry and my shared healing through our newfound relationship. [Editor’s note: McKenna has described her and Larry’s common understanding of grief, Larry having lost his son just a few years before connecting with the artist.]

What do you hope the viewer will take away from the work highlighted here?

It is my hope that viewers can connect with my endeavor to work through feelings surrounding loss and grief. These feelings are universal and I hope to open a conversation about grief and how people often experience transference from one human being to another.

Likewise, art is about making connections with others and the constructed nature of our relationship calls attention to what it means to find beautiful and meaningful connections in strangers.

Born in Rhinebeck, New York, and longtime resident of Woodstock, New York, Eliza McKenna divides her time between the Hudson Valley and New York City. After graduating from Wesleyan University with a degree in film studies, she received her MFA in Photography from Pratt Institute.

Having grown up in a community overrun by opioid addiction has given her a conscious view of impermanence and its effect on community. After losing her brother at a young age to heroin addiction, she began to question the world around her and found that photography was a meaningful outlet for understanding grief and loss. During her sophomore year at Wesleyan University, she began a project titled Please Have This Room Made Up, in which she photographed in various hotel rooms to recreate her imagined memory of her brother’s death. Using the pictures she made during this time, she built a photobook that currently lives at Wesleyan University.

While continuing this project, Eliza’s father became sick with a neurological disease that began to deteriorate his brain and motor function. Eliza, having had a spiritually intense relationship with her father, began suffering from intense depression and anxiety as she watched her father’s health worsen. After his traumatic death, a man named Larry immediately reached out and an unforeseeable photographic collaboration began to ensue.

A Place to Begin Again

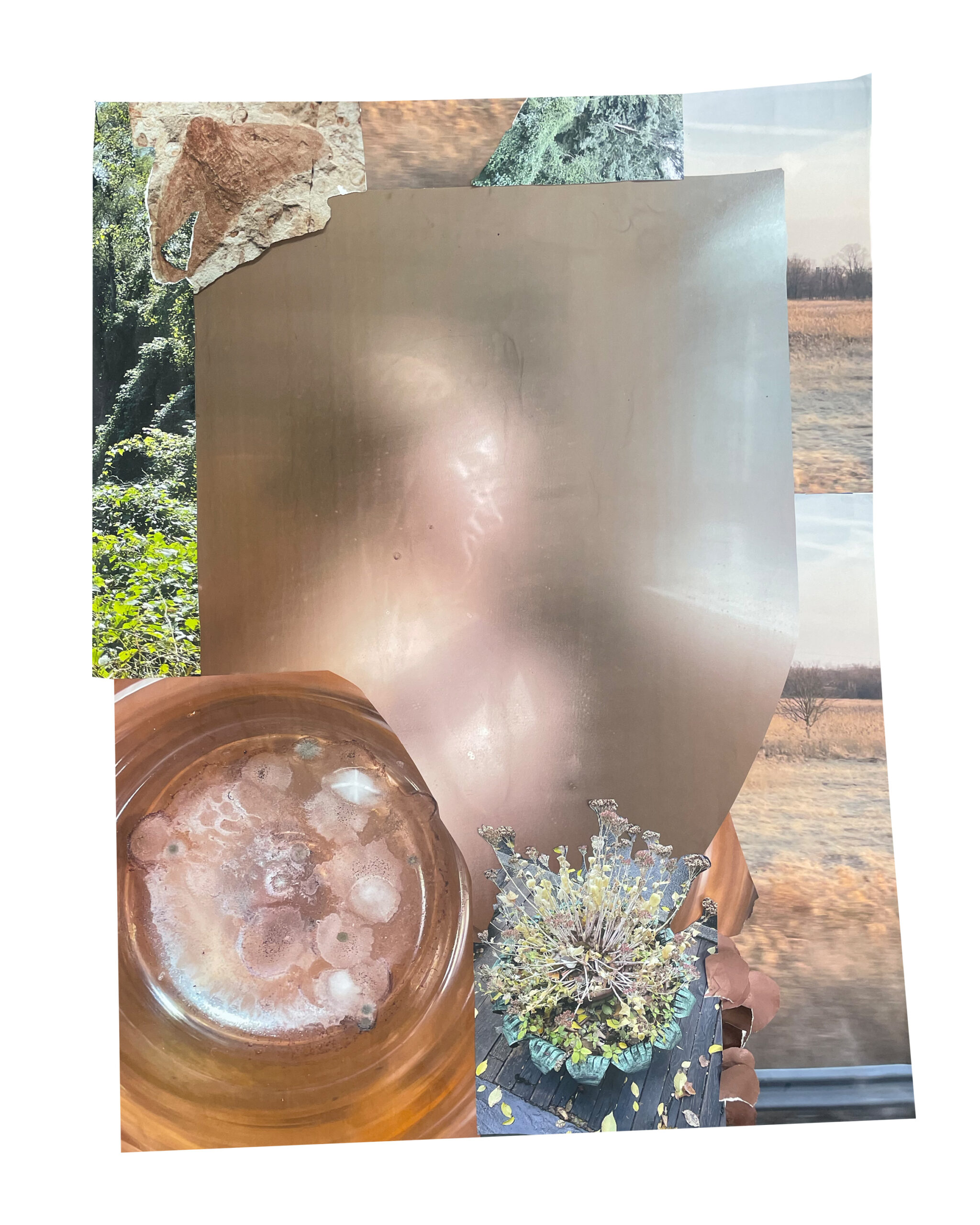

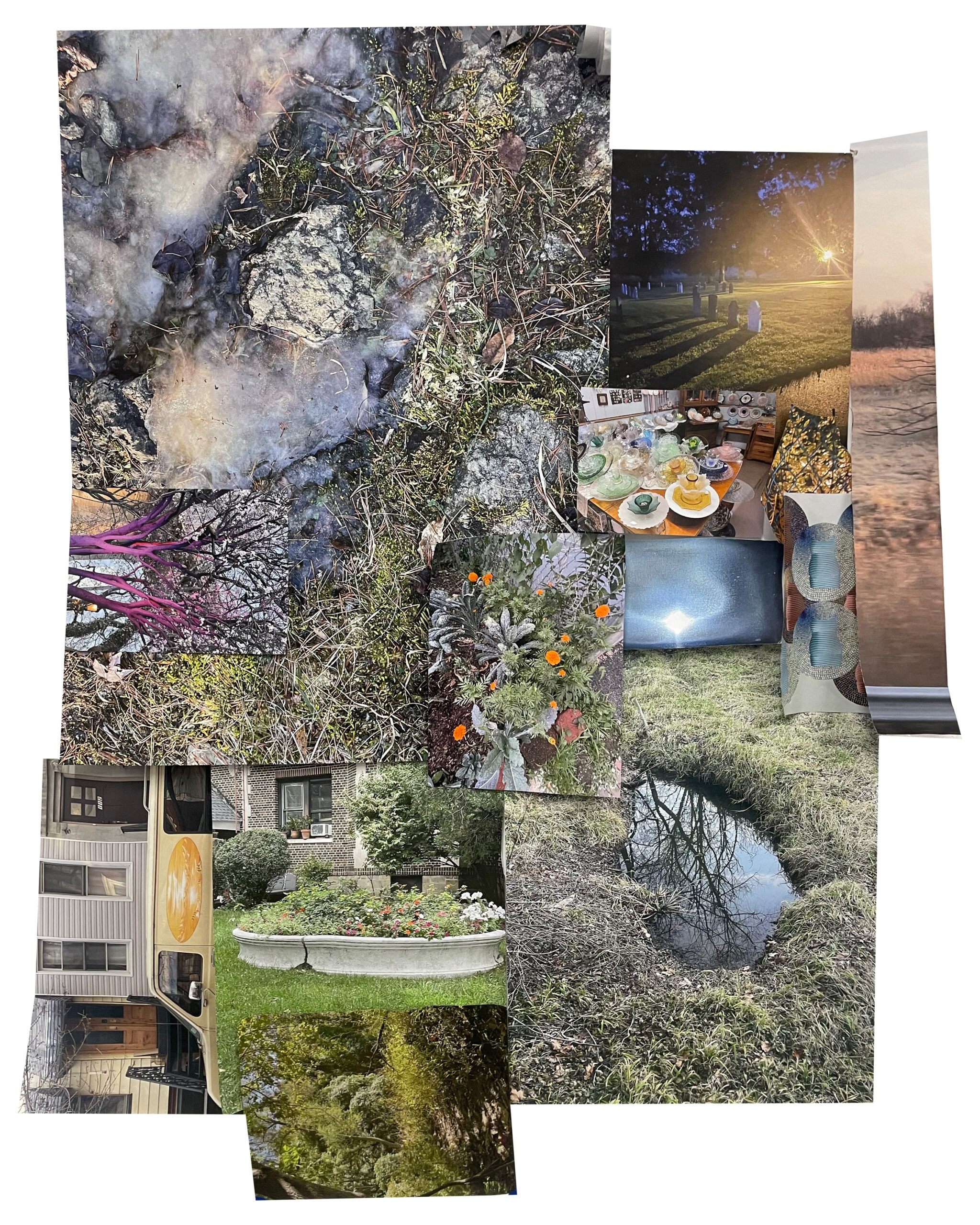

Raised in Baltimore before moving to New York City, Madeline McQuillan, BFA Photography ’23, creates a new sense of home with her work A Phenomenal Sanctuary, presented in an installation for her senior showcase at Pratt last spring.

What is the significance of home for you in your work?

Growing up around Baltimore certainly has influenced my sense of home and sanctuary—many of the images of nature included in my A Phenomenal Sanctuary panels are from parks in and around the city. The particularity of how densely green it is always feels like home to me. Ironically invasive, the Tree of Heaven makes a consistent appearance in my work because I am interested in how quickly it grows.

Living in a vibrant neighborhood where there was always something going on, be it the planned tradition of a decorated bike parade, or infectious, spontaneous hours of play, instilled in me the importance of sharing in acts of joy as often as possible, which is central to my project.

Living in New York has presented new challenges for me, and one way that I approach building sanctuary in a new place is through walking and looking for tableaux of new signs and symbols. They become personal landmarks, or temporary monuments to collections of my experiences.

The act of collecting slowly over a long period of time became the foundation of my project. The parameters for this collection are things that either fall into a string of patterns I find, or things that surprise me. Creating a sense of familiarity through pattern, and connecting to wonder is what helps create the mental fabric of “home” for me in Brooklyn.

I find that more and more places in and beyond New York and Baltimore feel like home as I develop this playful lens of searching for the photographic in the wild. Observing marks that show interrelatedness of objects and the passing of time develops a humor that creates lots of full-circle moments, so in a way, that past can always be accessed.

What are some sensations or ideas that define home—what do you imagine when you envision home—and how do those feelings or concepts relate to A Phenomenal Sanctuary?

Home is very sensational. I am enormously lucky to know that I can always return home to my family. Home is surrendering to the sensations—this is something we can do anywhere to feel more grounded in our bodies; this is a practice we can do that is private, and can’t be taken from us.

Home is slowness. As I wrote in my Field Guide [a book of black-and-white photos and writing that accompanied the A Phenomenal Sanctuary exhibition]: “a phenomenal sanctuary is a place where we can go to experience a now that can be stretched as long as we want it to be.”

Home is the small place in the world where things feel right. That “feeling right” is so liberating and grounding. Tuning into the interconnectedness of things is key in my project— creating familiarity with the rhythms of the world, whether it be in cities of contrasting pace and humors, or to the quirks of your surroundings.

How have your perceptions of home changed over time?

Home is where we can begin again, and it’s a place where we can revisit and reenact our own inner sense of magic, in spite of whatever pressures work to sever that connection.

Home is the starting point, or the center. In my Field Guide, I wrote, “I want to live in a house in the shape of a spiral,” which, to me, points to a desire to cultivate a space both of outward extension and retreat.

Making a home is a careful and slow process of tending to one’s needs; home is really the place where we most intimately meet ourselves, and can build a space where the primary concern is love, and care. We owe it to ourselves, and that’s why I build these haphazard models for love and care in the photographic.

What do you hope the viewer will take away from the work highlighted here?

Home is about being a part of a larger community, which is why my work invites people to stand in a circle and share a tactile experience. When our ideas and values can be felt through sensations—like observing a reflection and sharing in the breaking of the image by touching the water—we become neighbors sharing in a brief exchange of wonder and communion with the fantastical in our environment. I hope to encourage an engagement with the underlying current that connects us.

Madeline McQuillan is a fine artist working with photography in Brooklyn, New York. She graduated from Pratt Institute with highest honors in 2023, with a BFA in photography. Originally from the Baltimore area, she studied visual arts at Carver Center for Arts and Technology, where she followed vigorous painting and photographic pedagogies. She is passionate about developing new ways for the larger public to engage with visual art, and believes the transformative properties of the photographic remain abundant and largely untapped.

Origin Stories

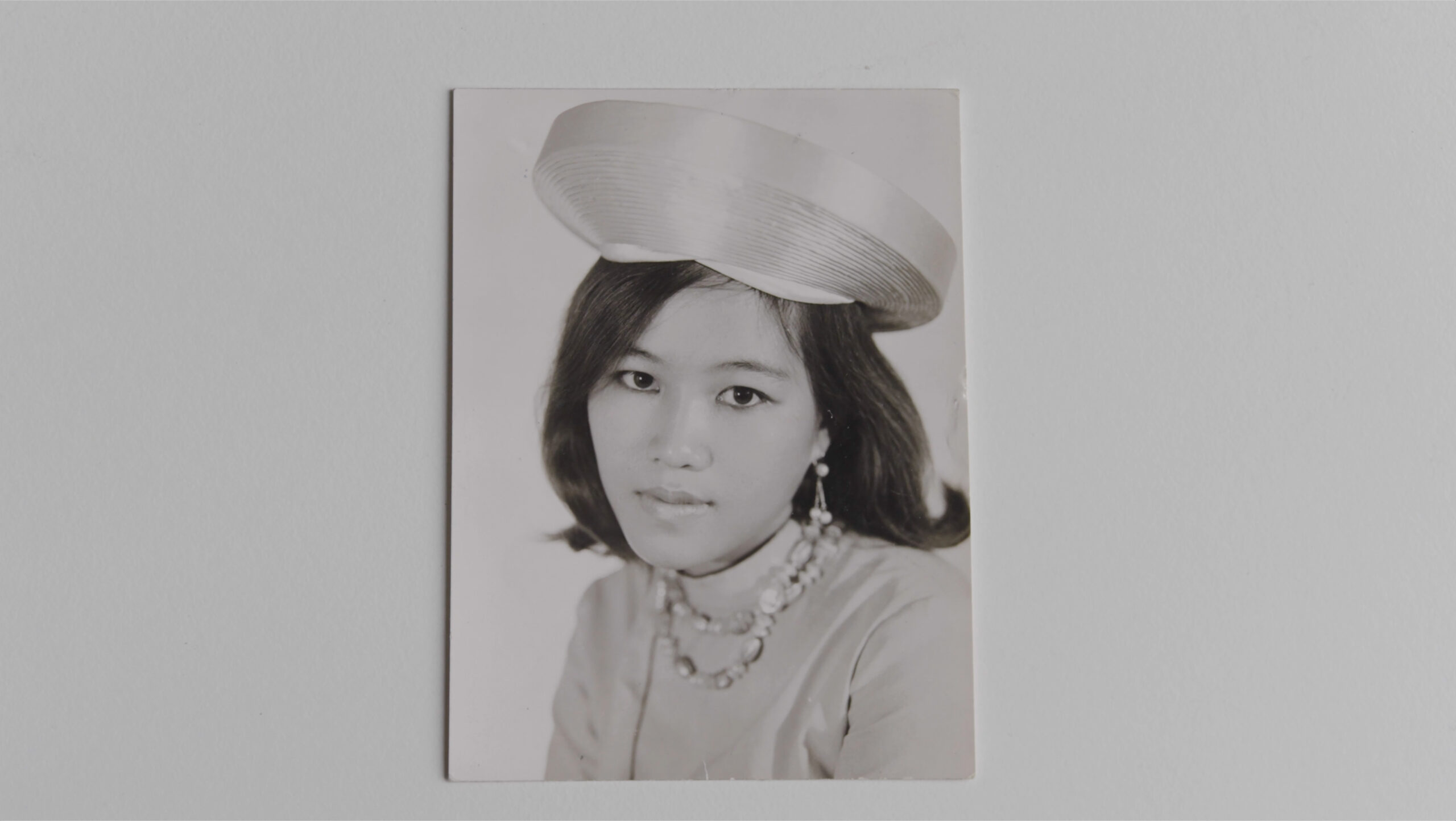

Shaping intimate portraits through images has been central to the practice artist-journalist Kevin Truong, BFA Photography ’13, has fostered, connecting him to people and communities around the world. But in his film project “Mai American,” his most tender subject is right back where he began.

What is the significance of home for you in your work?

My current project, a personal documentary about me and my mom, is deeply rooted in the idea of home. In fact, the film’s synopsis starts with, “In a tiny home on the outskirts of an Oregon forest, a mother and son—Tot and Kevin—navigate the mundanity of intergenerational living with their five cats.”

The catalyst for my film happened not too long after I graduated from Pratt Institute, when I found myself living back home with my mom in Oregon. At first, I felt a certain way about living at home as an adult, but then I started filming my mom to help bide my time—and now I’ve been filming her for more than 10 years. It’s interesting, before I moved home, I had spent a year traveling one-way around the world photographing and documenting the stories of queer men in their homes for a photo project called The Gay Men Project—which I actually started as a photography student at Pratt. Over the course of a few years, I had photographed over 700 queer men across 37 countries. I had literally traveled the world in search of interesting and powerful stories, but one of the most powerful stories I’ve ever worked on has been my mom’s story—which is right here at home.

What are some sensations or ideas that define home—what do you imagine when you envision home—and how do those feelings or concepts relate to “Mai American”?

As a filmmaker, I’ve put a lot of work into visually creating a sense of place while working on “Mai American.” In essence, I have approached filming my mother’s home much like an archeologist would approach sifting through an archeological dig. Everything in my mother’s home is given importance; the details shown in the trinkets she collects and the disorder in the way her pantry shelves are stocked help to paint a portrait of who my mother is as a person. As much as my mom and I are characters in this film, so are her home and Oregon, and visually, a home is made up of the things it is filled with.

Can you speak about a work of yours, or by another artist, related to home that revealed something to you?

I’m interested in building a world, not just a story. This is something I draw inspiration from through my favorite filmmaker, Hayao Miyazaki. For anyone familiar, they know Miyazaki doesn’t work in the world of documentary. He works in the world of anime and has made some beautifully crafted films during his time with Studio Ghibli. To me, what makes these films so beautiful is the world he builds in which all his characters live. Loving detail is paid to even the smallest things—the slight movement of a butterfly or the leaves on the branch of a tree during a breeze. As I mentioned earlier, this helps to create a sense of the monumental in the seemingly mundane—dust in the afternoon light or my mom hand-rolling egg rolls are given significance in the building of my film.

How have your perceptions of home changed over time?

I’ve worked on “Mai American” for more than 10 years, and have been living at home with my mom for the majority of that time. (I spent time back in New York City for graduate school.) I think what I’ve learned is that although I’ve spent a lot of time creating a sense of place visually in the home I share with my mom for my film, a home is so much more than that. It’s a feeling, it’s familiar, it’s safe. I believe everyone has a right to these things if that’s what they desire.

What do you hope the viewer will take away from this film?

A lot! But maybe if after someone watches my film, they phone an aging parent or loved one and take some time to learn more about their story, I’ll be happy.

Kevin Truong is a Sundance-supported artist whose work spans photography, journalism, and filmmaking. As a filmmaker, he has received fellowships from both the Center for Asian American Media and BAVC Media, and his work has received support and funding from organizations such as the Sundance Institute, MacArthur Foundation, A-Doc, California Film Institute, SFFilm, Regional Arts and Culture Council, Haverford College, and the Portland Events and Film Office. As a journalist, Kevin has written stories for NBC News and Motherboard Tech by VICE and has worked as a producer with Student Reporting Labs at the PBS NewsHour, and his photography work has been highlighted by media outlets including Le Monde in France and O Globo in Brazil. Kevin has a BS in economics from Portland State University, a BFA in photography from Pratt Institute, and a MA in journalism from the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at CUNY.

In his film “Mai American,” a 70-year-old Vietnamese American refugee living in Oregon writes down her life story, indelibly shaped by the war in Vietnam. As she shares what she has written with her filmmaker son, they begin separate but parallel journeys confronting the traumas of their past and the emotional divide in their present.

A Place Made Up of Other Places

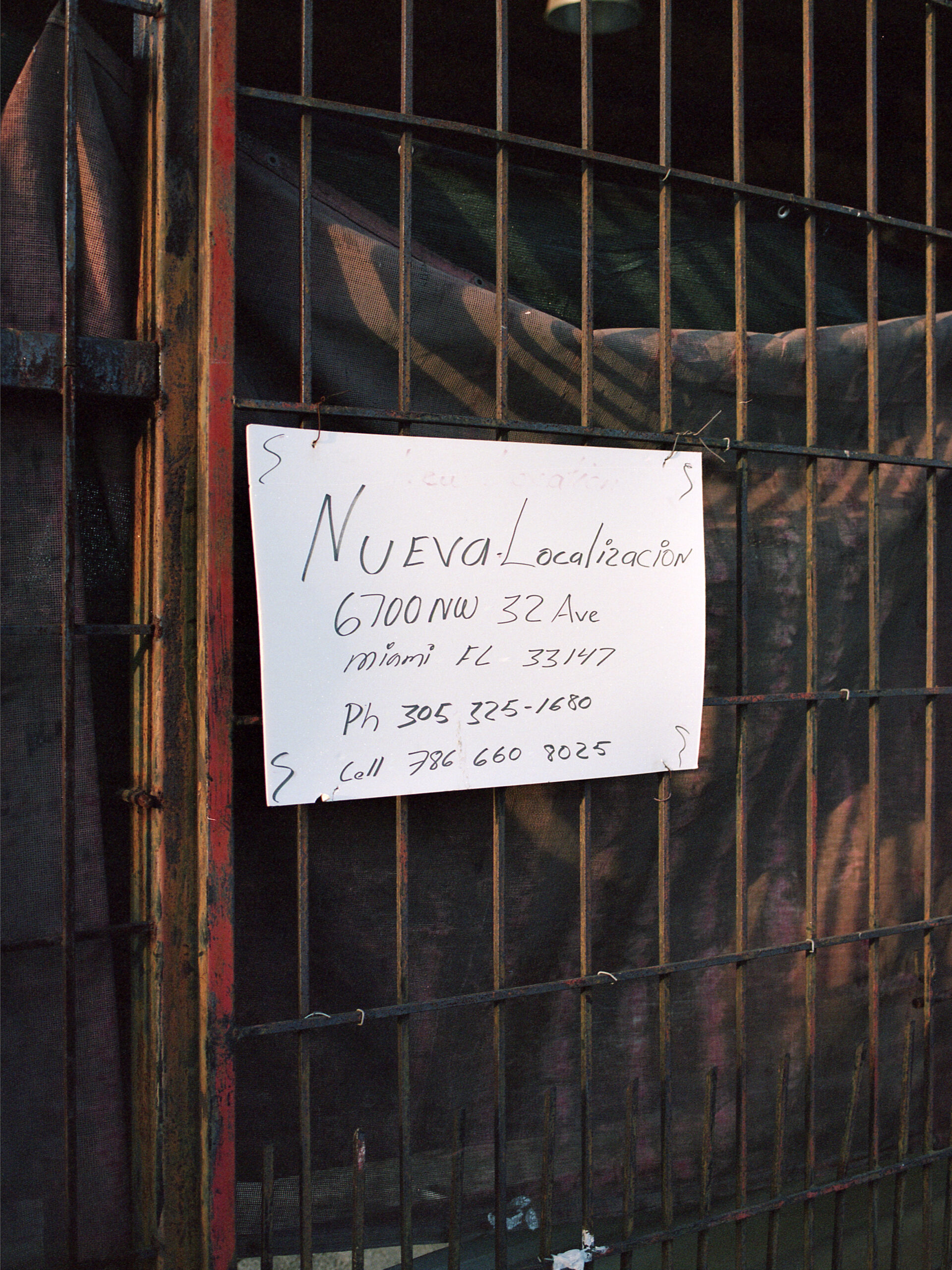

With the project In Rhythm with the Tides, Martina Tuaty, BFA Photography ’18, shines light on the rhythms, time, and vibrant life of her Miami home. In early 2024, the first iteration of the project will be published as a book by Ardent Projects.

What is the significance of home for you in your work?

Home is quite important in my current work, as it’s the first time I am really delving deep into my personal experience living in Miami. Although I grew up here, it wasn’t until I left for a few years and came back that I really formed a profound interest in exploring the layers this city is made up of.

What continuously draws me back home is the complexity of this place—the contradictions and misconceptions. Although this city is constantly in flux, when you linger and truly observe, the pace here can also be quite slow—the long wait for the arrival of mango season and summertime, the abandoned building on the corner that just seems to be slowly rotting away, and the way the shadows grow longer as you watch the day go by. This city is not one or the other, it’s a place made up of other places.

What are some sensations or ideas that define home—what do you imagine when you envision home—and how do those feelings or concepts relate to your current project?

Warmth, slowness, connection—when I think of home, I think of comfort. In my project, In Rhythm With The Tides, all of these ideas are at play. At its core, the project is about slowing down; connecting with others as a way to connect to yourself and your environment, exploring daily life as a ritual.

How have your perceptions of home changed over time?

Having moved to the United States from Italy as a young child, my perception of home has always been a bit layered. I’ve definitely been heavily inspired by my background, my mother’s side from Italy and my father’s from Colombia. For a long while, I think the idea of home was not so clear to me, and it took some time to understand what I wanted it to look like for me. But right now, it feels as clear as ever that Miami is exactly that. It’s hard to express, but there’s an energy in Miami that feels familiar and comforting; like home.

What do you hope the viewer will take away from the work highlighted here?

If anything at all, I hope the viewer feels a sense of calmness; that they take the time to think about and question what it is they are looking at. Even if it is just a feeling that they get, I hope it is one of stillness, sort of like a meditation. For those who may be unfamiliar with Miami, I hope this work offers a different perspective than one they may see in mainstream media. Ultimately, I just want the viewer to feel something, and I’m interested to see how the work resonates differently for people.

Martina Tuaty (born 1996 in Florence, Italy) is a photographer and artist whose work explores the commingling of disparate yet linked moments that become unified through common everyday experiences. She is constantly inspired by light and shadow and is interested in addressing ideas around place, memory, and human connection through her work. Recent clients include The New York Times and The Washington Post. Martina received a BFA in photography from Pratt Institute in 2018 and is currently based in Miami, Florida.

Family Ties

Vanessa Vargas, BFA Photography ’18, mines personal history and heritage in two works that examine and preserve details of her loved ones’ lives, across time, homes, and nations.

What is the significance of home for you in your work?

The beauty of a photograph is the ability to preserve a fragment of time for longer than it exists. The idea of home became a focus in my work as I experienced different transitional periods in my life and time passing meant more loved ones passing, traditions changing, and my family’s connection to their home country of Peru lessening. Wanting to protect certain aspects of homes while also exploring the differences I noticed drew me to the most lived-in spaces—the living room, dining tables, and bedrooms—areas that would change often with one’s presence and, as showcased, time passing.

What are some sensations or ideas that define home—what do you imagine when you envision home—and how do those feelings or concepts relate to And They All Came Back and Hasta la próxima vez?

Growing up, the idea of home had oftentimes been synonymous with the idea of family. As a daughter of immigrants, I was raised with a mix of values and traditions that have continued to shift as I’ve gotten older, but maintaining our family relationships has always played the most important role in establishing a sense of home.

Being raised surrounded by people who had very different experiences growing up in a different country, I had difficulty understanding the stories of their lives even though they deeply interested me. And They All Came Back began with a curiosity to explore my own connection with my family’s history. I searched for moments in their photographs that I could relate to even in the simplest of ways—a child looking through the window, white doilies on the tables, a girl (my mother) with her dogs on the steps. I gained more insight on the people I’ve known my whole life through viewing the homes they grew up and lived in, the way they decorated the rooms, and their documented pastimes.

I started to piece together my more recent project, Hasta la próxima vez, as a way of preserving one of the most important figures in my household, my grandmother during the last years of her life. Undoubtedly the matriarch of the family, her presence was interwoven with my idea of home from a young age. After photographing my grandmother with her younger sister, now the last remaining sibling of six, it was a natural progression of the project to include my great aunt and her home in the work as well. This body of work easily comes from a place of admiration for these two women who moved their families to a new country when they were younger and hoping to save the precious details of their lives forever even as life continues to move forward.

How have your perceptions of home changed over time?

My perception of home has only really expanded as I’ve gotten older. With such an emphasis on the importance of familial ties as a child, I believed there was also a need to stay nearby even into adulthood. But the idea of home has now solidified itself into more of a feeling of peace and belonging that can be felt in more places than one, and with more groups of people. Family will always be a large part of that for me, but my newer views have allowed me to also find “home” in other places while knowing that I’ll always have a place and people to come back to.

What do you hope the viewer will take away from the work highlighted here?

I would hope for viewers to come away with a new or a renewed interest in reflecting on their family’s heritage. There is such a generational gap between people and their elders that reflecting on one’s personal history and finding moments of connection can be beautiful.

Vanessa Vargas is a visual artist who works primarily in a photographic medium. Her practice often revolves around the ideas of memory, preservation, and familial relationships as a form of reflecting on the connection she has with her heritage. She enjoys documenting the beauty of ephemerality through small moments in everyday life.