For the Fall/Winter 2020 digital issue of the magazine, produced during this time of physical distancing, Prattfolio collaborated with faculty members on virtual tours of the places where they are working now. This spotlight on Claire Donato, a writer and adjunct associate professor of writing at Pratt, who has been named the Institute’s Distinguished Teacher 2020–2021, is the first installment of the issue.

Donato—author of the novel Burial (Tarpaulin Sky Press, 2013) and the poetry collection The Second Body (Poor Claudia, 2016; Tarpaulin Sky Press, 2020), among other works—writes in various settings at home in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant neighborhood, near Pratt’s Clinton Hill campus. The below words about the space are Donato’s own, with photographs by friend and collaborator Felix Walworth.

On the space

I’ve been living with my cat, Brix, and approximately 50 houseplants in a 1.5-bedroom apartment located in a psychic medium’s brownstone in Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn. [During the production of this story, Brix passed away, over Rosh Hashanah.] My landlady, Emily Grote, has deep connections to Pratt Institute, which you can read more about on her website, thus my living here feels kismet. I feel very lucky to rent from long-time Bed-Stuy homeowners whose building is a safe haven.

My apartment is located across from a stunning stone church called Our Lady of Victory, which used to be a shelter for people with alcoholism who were homeless. There’s a garden attached to the church with a sculpture of Saint Maximilian Kolbe, the patron saint of addicted people, who gave up his life so a stranger could live at Auschwitz. There is also a sculpture of the Virgin Mary and, of course, of Jesus. I try to visit this garden once a day, and when I do, I always touch Saint Maximilian Kolbe’s hand and pray for the parts of all of us that are a little addicted.

My apartment—my shelter—is very quiet. It feels hackneyed to say, but it is my sacred space. Visitors always remark upon my apartment’s silence. Some have said its energy feels like a monastery. This description feels apt. From May 2019 to February 2020 (before COVID-19 shut down the world), I was spending a lot of time at Zen Mountain Monastery in Mount Tremper, New York, and the monastic rhythms I experienced there deeply shape how I live: I meditate for 35 minutes to an hour every morning upon waking, and often before bed; I intuitively clean for 25 to 30 minutes a day; I approach cooking as a contemplative practice.

I’m including photographs of three surfaces I use to write—and, now, teach. One is my kitchen table; one is a small, mint-colored desk in my bedroom; the third is a glass desk in my office. I use these surfaces interchangeably. Presently, I am writing this from my bedroom desk.

Rituals and transitions

My practice has shifted a lot over the past six months. Because so much of my energy was transferred into the computer due to COVID-19, I had to find other ways to write offscreen. I began journaling more by hand, and became very dedicated to songwriting. Currently, I’m at work on a full-length LP of songs. Felix Walworth, who took the photographs for this spread, and who is wonderful, is mixing the record. You can listen to a track called “Mother Like You.”

In addition to songwriting, I took up a 35mm photography practice, and have returned to making one-panel comics that incorporate text from my handwritten dream journal, and non-dream journal too. I take long—sometimes two- or even three-hour walks—as often as I can, and on these walks, I take photographs. Photography, I find, helps me turn outward toward the world. My camera is a refurbished Pentax H3 camera from 1961.

A decade ago, I wrote many comics, and for some reason I stopped. It’s felt good to reinaugurate that practice. The images I illustrate typically come to me during meditation; in other words, they burgeon from my unconscious.

Beyond the above, it’s been grounding to maintain a morning routine. I wake up, make grilled gluten-free toast in a cast iron pan, and drink a matcha. I then meditate for 35 minutes to an hour. Subsequently, I set a timer for 25 to 30 minutes and intuitively clean. Then I practice yoga. Then I get to work.

Items of importance

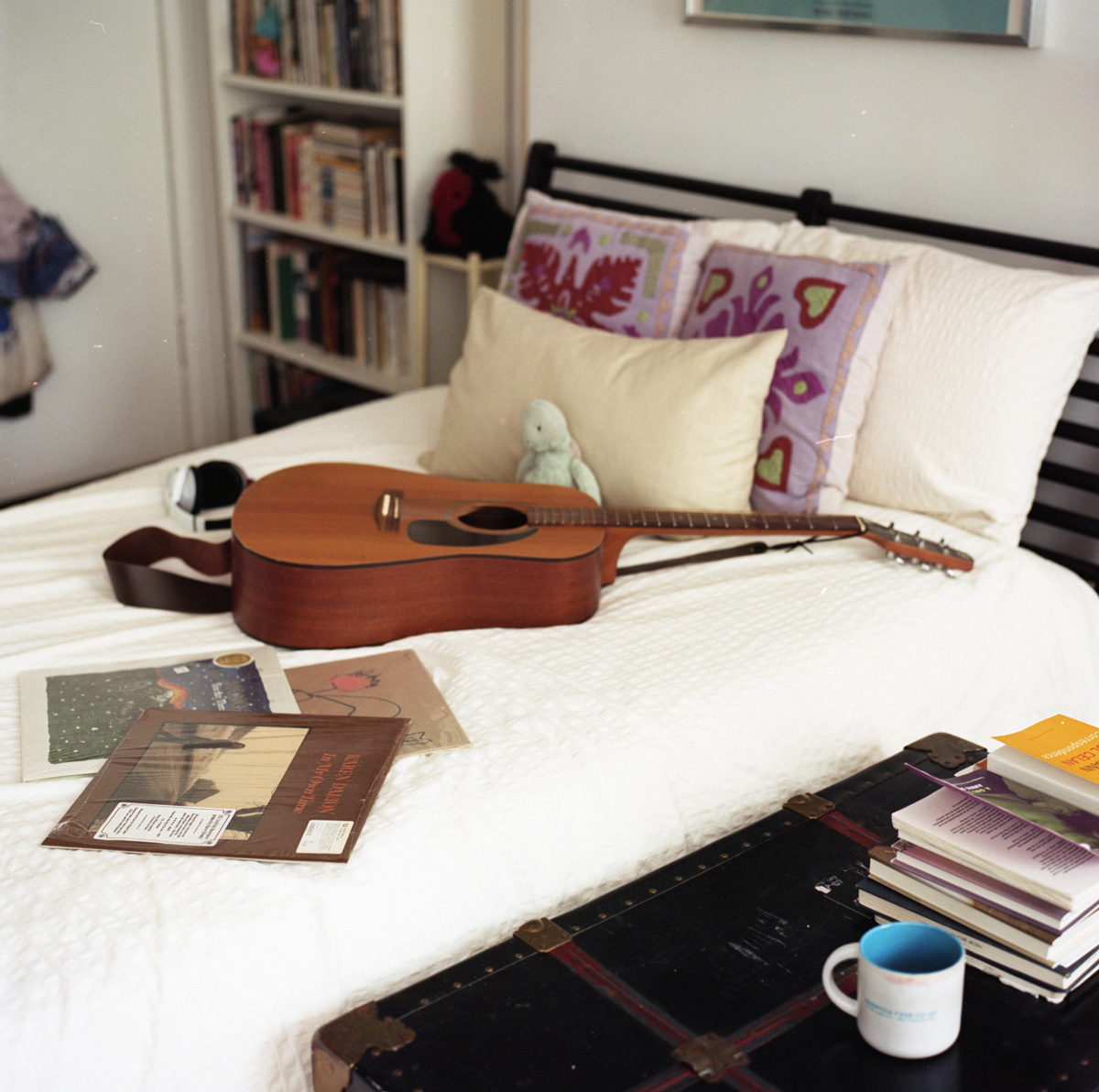

Some significant objects pictured here include my guitar. I began singing when I was very young and quit after I finished my undergraduate studies. This year, after learning to breathe and falling in love with Zen meditation, I started singing again, and writing songs. My stuffed turtle, who visited the monastery a few times, is looking over the guitar [above left]. And there are some records on the bed: Karen Dalton’s In My Own Time, Mono’s You Are There, Rainy Day’s self-titled LP.

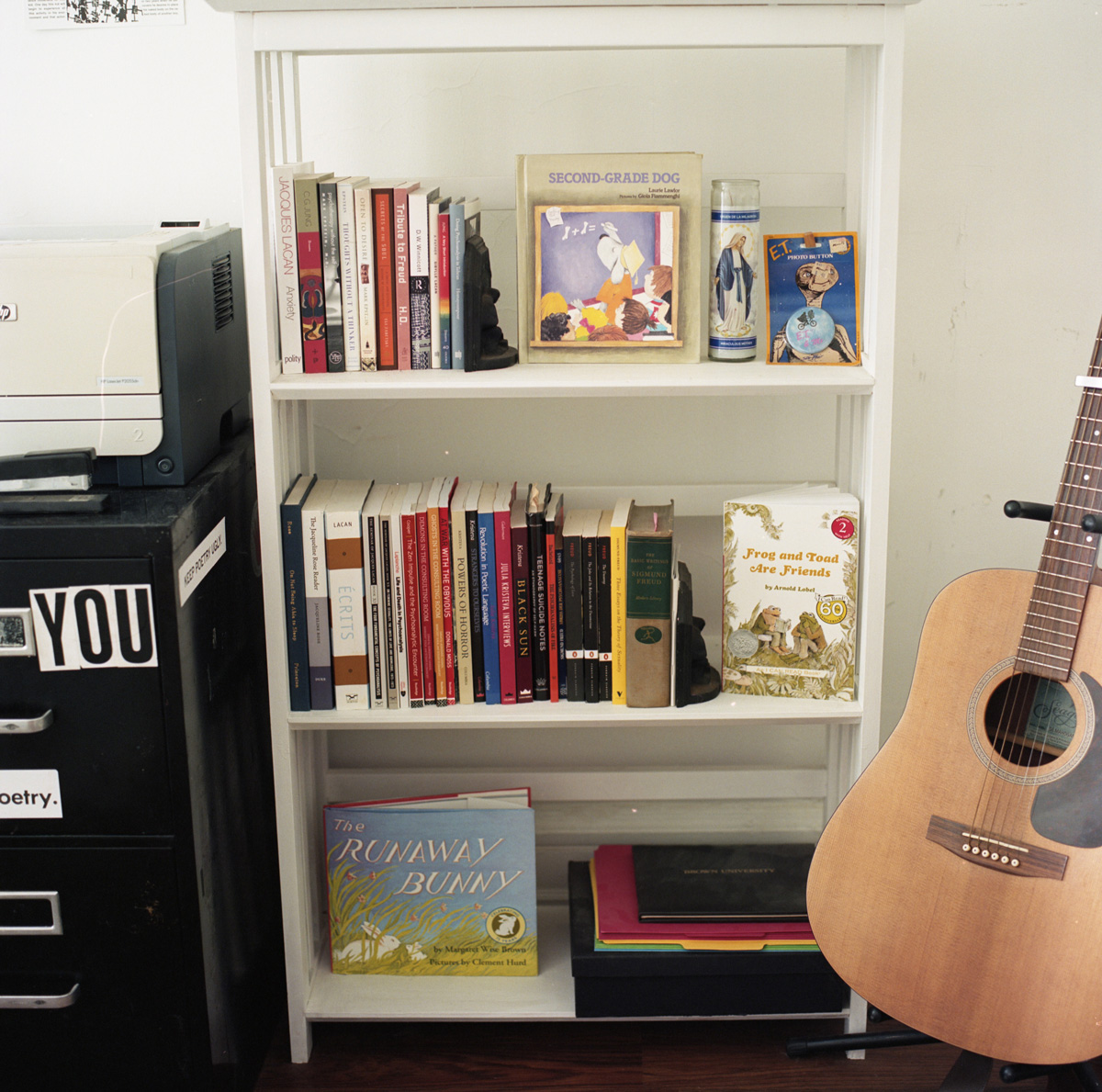

I’m also including a photograph of my psychoanalysis bookshelf [above right]. I am a student of psychoanalysis: I’ve been in multi-day-a-week analysis for three and a half years and consider it part of my writing practice. At Pratt, I’ve taught poetics electives called Poetry and Psychoanalysis, The Oceanic Feeling (a term popularized by Sigmund Freud via Romain Rolland), The Poetics of Love, and Silence. All of these electives draw upon concepts from analysis found in the books on this shelf.

I’ve juxtaposed these books with some favorite childhood books and media—The Runaway Bunny, Frog and Toad Are Friends, Second-Grade Dog, and E.T.—because I think reckoning with one’s inner child is integral to healing. Along these lines, I’ve also included a drawing I made as a child [top right]. It says Claire’s life is sometimes fun. Sometimes it is sad. It hangs above one of my desks next to David Wojnarowicz’s Untitled (One Day This Kid . . .), an homage to my queer ancestors.

Finally, I am including images of my cat, Brix, sleeping next to my meditation and yoga supplies [above center], and an image of the dream journal in which I write every morning [top left]. Next to the dream journal is a Celestine crystal. Sometimes I sleep with it close to my head so I more deeply dream. My favorite definition of dreaming is thinking in the form of an experience. Each morning, upon waking and recording my dreams, I hold this definition in mind and ask myself: So what did you think about the experience?