Throughout its history, Pratt Institute has been a fertile site for research—from the earliest drawing classes that helped students explore the visible world through their own hands, to technological study that shaped emerging manufacturing fields during the early 20th century, to aesthetic and theoretical investigations that formed the foundations of art and design education.

With its emphasis on educating for disciplines grounded in inquiry, Pratt continues to support knowledge creation that enriches scholarship and society. Over the past few years, with the formation of the Office of Research and Strategic Partnerships, Pratt has begun crystalizing a cohesive research community, uniting the efforts of faculty, students, and staff and linking their investigative work with the world.

Associate Provost for Research and Strategic Partnerships Allison Druin has set the mission of her team to uncover, communicate, and cultivate scholarship, activism, and academic leadership among researchers at Pratt. The annual Pratt Research Open House has grown to present more than 50 Pratt-affiliated research projects to the Institute, government, industry, and alumni communities each spring. A recently launched Pratt Research Seed Grant Program supports researchers across the Institute aiming to jumpstart a project. And creating space for ideas and explorations to progress side by side has also been central to Druin’s team’s work.

This year, they transformed an available Pratt space on 18th Street in Manhattan into a hub for research leaders who lacked a dedicated place to advance their projects, with the complementary goal of introducing opportunities for collaborative networks to blossom. More recently, with the support of Brooklyn Navy Yard and the New York City Council, a new space was conceived that would allow Pratt research activities, community outreach efforts, and student learning to merge at the Navy Yard, just steps from Pratt’s Brooklyn campus. The facility is expected to be up and running by late 2020.

To learn more about the questions Pratt’s research community is pursuing, Prattfolio spoke with just a few of the investigators within its ranks, who highlighted the challenges their work addresses and the emerging tools and methods that are building new knowledge in their fields and the world at large.

Probing the Meaning of Progress: The Global South Center

Entering the Global South Center’s sun-drenched space in Manhattan, a long table beckons—an invitation both to dig in to rigorous work and to connect in the spirit of curiosity and cooperation most easy to find when we sit face-to-face. Led by founder and Director Macarena Gómez-Barris, Chair of Social Science and Cultural Studies, the Global South Center has created an academic hub at Pratt for scholars and researchers citywide to come together and explore social issues across the geopolitical landscape. In collaboration with an energized global scholarly community, the Center’s work reexamines assumptions about what it means to advance in a world divided by inequity, collectively imagining a more just and decolonized future.

Questioning Injustice

“The big issue or concern we deal with in the Global South Center is how to address the growing inequality and environmental disparity between the Global North and the Global South,”1 Gómez-Barris says. At the center of their investigations, the Global South Center looks at how people and communities in regions affected by environmental, economic, and political disruption are advancing the conversation. “Despite gloom-and-doom empirical realities, the Global South is also where many artistic, interdisciplinary, design, and sustainable solutions foment, not only to adapt to worsening conditions, but to actively resist and refuse what is increasingly a dominant imaginary of planetary disaster.”

Scholarship to Action

The Global South Center’s scholarly work has crossed into the public realm through several projects emerging from pressing issues, from land and water defense in Indigenous territories in the Americas to career pathways for young people of color and immigrants in upstate New York. Currently underway is a project that charts the presence of plastics in oceans and waterways, examining the link between sites of dense pollution and industrial production. “We believe that we must enliven experimental work, conscious urban design projects, decolonial theory and praxis, anti-racist practices, and social movements in the Global South and amongst communities of color in the Global North,” Gómez-Barris says. “It is from these spaces that we will learn to get out of the impasse of developmental thinking that assumes progress is tied to material wealth for the few at the expense of the many.”

Stretching the Conversation

“We are lucky to have an extensive network of artists, scholars, designers, architects, and activists currently engaging with us,” Gómez-Barris says, noting that beyond its events in New York, the Center has held workshops, forums, and seminars in Belgrade, Mexico City, Cairo, Sydney, Melbourne, and Santiago, with more to come. “We feel fortunate to be at an art and design school that values the importance of social context and imagining new worlds through collaboration.”

1 The terms Global North and Global South refer, respectively, to countries where wealth and geopolitical power are concentrated and countries of mostly low income that have experienced political and cultural marginalization.

Quantifying Our Relationship with Our Environment: Interdisciplinary Technology Lab

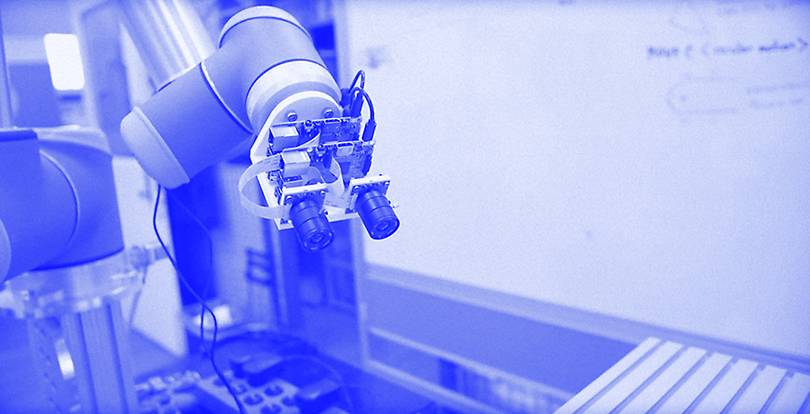

Gathering around a tower of cameras, monitors, and motion-tracking technology in the space where the Interdisciplinary Technology Lab (ITL) conducts its research, the room around us comes alive as a site for potential data—traces of information about our habits of motion and interaction. These points of data are central to the investigations of

ITL’s Medium Analysis Group (MAG)—led by Richard Sarrach, BArch ’01, Director of Interdisciplinary Technology and Adjunct Associate Professor CCE of Undergraduate Architecture; Ted Ngai, Visiting Associate Professor of Undergraduate Architecture; and Scott Sorenson, BArch ’10, Visiting Assistant Professor of Undergraduate Architecture—which is looking at how sophisticated metrics on human behavior could enhance design. By analyzing evidence of how people use space, MAG aims to create “more intelligent feedback loops between the physical and virtual worlds,” as Sarrach puts it, and position architects and urban designers to bring more of the human condition into human environments.

The Site of Inquiry

MAG’s research is spatial prospecting—to collect, analyze, and mine spatial data—to reveal human macro- and microstructures hidden deep in our spatial and temporal dimensions,” Sarrach explains. “We are developing novel ways to combine machine learning, computer vision, photogrammetry, IoT devices,2 industrial design, architecture, and urban design, to allow us to gain insights into the relationship between space, design, and human behavior.”

Habit Mapping

MAG’s research delves into two domains: public and private. Within the public sphere, the researchers use data to look for insights into how design can make social interactions easier. Their work in private spaces pursues information that could aid planning and management. According to Sarrach, the research “proposes a fully automated, autonomous, and anonymous approach to spatial and behavioral tracking using uncalibrated and unordered video footage and Building Information Models.”3 MAG proposes using video footage from existing security camera systems to isolate details about people’s movements in a space. Scanning those recordings, a state-of-the-art machine-learning algorithm detects movements and creates a 3-D dataset, which researchers can translate into a visual heatmap of activity.

Refining Process

The methods MAG is experimenting with strive to improve accuracy and eliminate bias in the way researchers survey how people use spaces and identify patterns in their movements. “Through the extraction of body gestures, we gain a better understanding of how people interact with objects such as urban furniture, sculptures, lawn, trees, and other types of urban objects,” Sarrach says. “This line of research will have a significant impact on the way we think about the design of our built environment—in the end, we are rewriting the design playbook.”

2 IoT: internet of things, the system of interconnected “smart” devices capable of transferring data.

3 Building Information Modeling is a computer-aided design process that captures layers of data about a building within a 3-D model.

Discovering Keys to the Ancient City: Laboratory for Integrative Archaeological Visualization and Heritage

Experiencing places rich with history can be a powerful means to understand where we stand in our society’s present and future, but as the Laboratory for Integrative Archaeological Visualization and Heritage (LIAVH) points out, for fragile sites dating to antiquity, access to that sort of exploration is often out of reach. Interested in what the removal of barriers to entry might mean for scholarly discovery and a community’s sense of belonging to a nation, the LIAVH’s interdisciplinary team seeks out innovative methods to explore the ancient world, with a do-no-harm approach. Led by principal investigators Uzma Z. Rizvi, Associate Professor of Anthropology and Urban Studies, and Can Sucuoglu, Interim Director of the Spatial Analysis and Visualization Initiative (SAVI) at Pratt, and cofounded by Jessie Braden, SAVI’s former director, LIAVH is embarking on its inaugural project, M_LAB, to explore how data mapping can make one of the world’s foremost architectural sites discoverable to all.

Questions of Time and Space

With existing 3-D modeling technology, it is possible to reproduce and observe sites of historical interest altered by the fluctuations of civilization and the physical world—but there is only so far researchers can delve into the human business that once defined these spaces. LIAVH sets that challenge at the center of its inquiry: “Is there a way by which we might plot data points—such as architecture, infrastructure, and artifacts—at different stratigraphic levels,”4 and in so doing, create a new way to visualize and study the development of cities over time?

Story of a Civilization

The group’s inaugural project, M_LAB, takes as its focus MohenjoDaro, an ancient settlement in Pakistan considered to be one of the most significant and influential planned cities of South Asia.5 Starting with one section of the city, M_LAB is mapping information about its spaces and artifacts using existing excavation plans and site reports, weaving together data to create a 4-D model that could help piece together a dynamic picture of a people across time.6 “The interactive tool proposed by LIAVH enables researchers, for example, to understand the historical cultures from an urban-planning perspective by analyzing change at the neighborhood level,” according to Rizvi and Sucuoglu.

Expanding Ancient Narratives

The MohenjoDaro project also addresses another quandary for investigators of the ancient world: The site’s protected status, while vital to its conservation, limits the potential for hands-on study and heritage-related exploration. Rizvi’s research group looks to solve the access problem by noninvasive—that is, virtual—means, with applications beyond MohenjoDaro. LIAVH’s ultimate goal for M_LAB, Rizvi and Sucuoglu say, “is to create an open-source software that could be utilized at any ancient city to create narratives from datasets to reveal archaeological information.”

4 Stratigraphy in archaeology looks at the layers, or strata, of a place through time, with older layers concealed by newer ones.

5 MohenjoDaro is designated a UNESCO World Heritage Centre, preserved for its scholarly and cultural value as the urban center of Indus civilization (third millennium BCE), one of the world’s major ancient civilizations.

6 The well-documented site’s wealth of archaeological details makes it an ideal case study. Data fields M_LAB is mapping include spaces’ area, function, and artifacts; streets’ width, drainage, and slope; and the characteristics of street intersections.

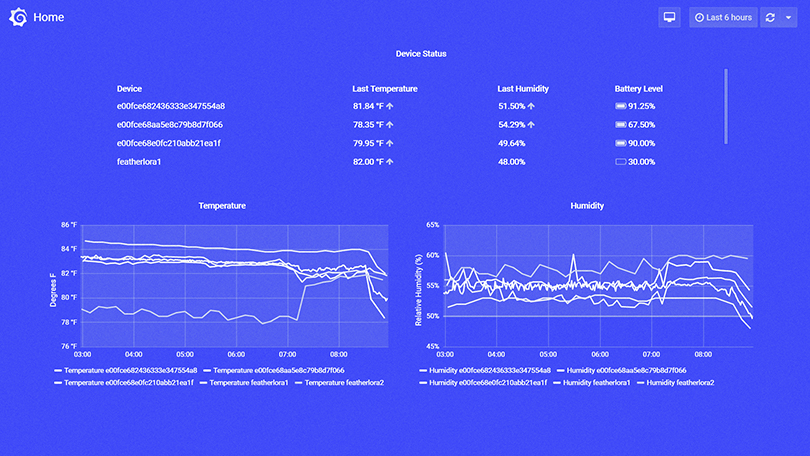

Monitoring with Maker Tech: Environmental Sensing Lab

Technology is computing the space all around us. In one area of the Environmental Sensing Lab, an unassuming plastic briefcase houses a data-collection system gathering information on high-energy particles in the atmosphere. In another, tiny sensors and monitors are relaying measurements of temperature and humidity in the room. Founded by physicist Helio Takai, Interim Dean of the School of Liberal Arts and Sciences, to facilitate his research on urban cosmic rays, the Environmental Sensing Lab investigates how physical computing devices can be used to observe environmental conditions. The lab recently expanded to include Gabrielle Brainard, Visiting Associate Professor of Graduate Architecture and Urban Design, who is collecting data on studios and classrooms in Higgins Hall, and Monica Maceli, Associate Professor in the School of Information, who has been working on a Pratt Research Seed Grant–funded study focused on observing conditions in archives and making the modes of data collection more accessible.

The Field of Exploration

Broadly, Maceli’s research looks at how libraries are using low-cost, open-source, customizable “maker” technologies,7 examining the benefits, challenges, and skills involved. Maceli’s project EnviroPi: An Open Internet-of-Things Approach to Monitoring Archival Collections focuses specifically on how physical computing8 devices can help cultural heritage organizations track the conditions of their archive environments.

Sharing Economy

The rapid pace of development for new physical computing systems has presented Maceli with exciting, widely accessible avenues for solving problems. EnviroPi addresses a particular challenge: how to make monitoring tools available to institutions unable to acquire expensive commercial systems. Maceli’s project experiments with low-cost, easy-to-obtain open-source hardware and software—components that are right at the fingertips of library and collections professionals.

Building the Network

For Maceli, research and teaching go hand in hand. Her exploration of applications for physical computing devices feeds directly into curriculum developments at Pratt, with potential for broader educational influence.9 “These efforts lower the barriers for other institutions interested in offering similar courses and/or topics in the future,” Maceli says. “This is of particular importance to the Library and Information Science field currently, as recent research indicates that there is a small but growing number of maker-related courses offered within Master of Library Science programs, and other programs will likely follow suit.”

7 “Maker” technologies, like sensors, microcontrollers, and single-board computers, enable low-cost, accessible, do-it-yourself construction of digital tools and other personally meaningful technology projects, and have become highly popular in educational contexts to support problem-based learning.

8 Physical computing relates to creating interactive systems, using hardware and software, that sense and respond to the physical world.

9 For example, a new Rapid Prototyping and Physical Computing course at Pratt gives students hands-on experience designing and constructing experimental devices—from a cat-operated thermal bed to a light installation that responds to touch.

Asking the Next Question: Design Clinic

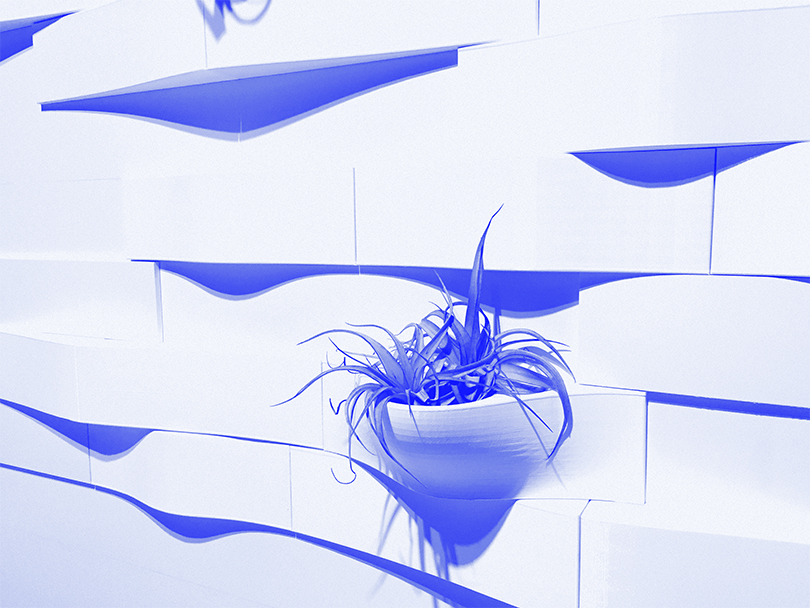

A reclining bench replaces a traditional bathtub. Pockets of moisture-thirsty air plants bloom from a wall tiled in gentle waves. Shifting light, inspired by daybreak, keeps the time. Design Clinic’s Future Bathroom 2025 invites us to imagine how peaceful, restorative, and, ecologically speaking, low-impact, the bathing experience could be. The project, sponsored by American Standard Corporation, exemplifies the concept behind Design Clinic, a program established by Constantin Boym, Chair of Industrial Design, “to investigate the role of reality-based action in today’s design academia,” blurring the line between educational and professional experience for students. In this “internal internship,” faculty and students work side by side to undertake real-life projects for a client, with a process structured around research principles of Pratt methodology.

Themes of Inquiry

“Like patients who come in to see a doctor,” Boym explains, “our clients approach Design Clinic with their ‘problems’ in search of design help.” For American Standard, the challenge was to create a bathroom that would minimize the user’s footprint and enhance their enjoyment of the space. To address this, Boym’s group explored three main areas: how design could conserve water, reduce labor, and create an atmosphere of calm that would give urban users respite from hectic city life.

Fresh Solutions

For Future Bathroom 2025, the design team proposed a gray-water system that routed used shower water to the toilet, which would save some 14 gallons of water per person every day. They proposed a prefabricated “wet wall”10 and fixtures to limit the trade-specific labor it takes to finish a bathroom. This was all balanced with elements that emphasized tranquility for the user: “Bathing and cleansing are no longer considered purely functional hygienic activities,” Boym says. “Our bathroom provided integration of technology with nature, from use of tropical air plants to moderate the humidity, to a show of light that rises like the sun to visualize the length of one’s shower.”

Thinking Forward

“Someone said we could have called Design Clinic ‘The Future Of,’” Boym remarks, noting past work on a future kitchen, the future of takeout, and the future of vinyl, as well as this year’s project on the future of wood, initiated by Associate Professor of Industrial Design Karol Murlak.11 “Opening up new lines of inquiry, envisioning something which has not been done before, acting in a responsible and sustainable way—these are directions of our research.”

10 A “wet wall” contains the pipes and drains in a bathroom behind a solid panel. The idea is that a prefabricated wall and fittings could be installed by a single construction crew.

11 Read more about Murlak’s spring 2019 Design Clinic project, HURRAH!