It was often called a furniture-making class, but instructor Gweny Jin both agreed and disagreed. “I would rather call it the class of ‘making things,’” Jin said in an overview of Family of Things, the Interior Options Lab she taught during her time as the Pratt Institute Interior Design Department’s AICAD Fellow, from 2021 through spring 2023. (AICAD—the Association of Independent Colleges of Art and Design—postgraduate fellows spend up to two years gaining teaching experience at a sponsoring school such as Pratt.)

“The idea of ‘Family of Things’ is for [students] to not only discover their unique linguistic solution to their individual style, taste, and design intent,” Jin continued, “but also to realize it in a sequence of working processes that then can become generative and leads to the potential of the making of a collection of pieces and eventually the making of space.”

This past spring, Jin and her students across four semesters presented hand-crafted pieces developed in Family of Things in the exhibition Ebb and Flow, held in the Juliana Curran Terian Design Center Gallery on Pratt’s Brooklyn campus. Along with the finished work, layered within the space were sketches, in-progress photos that captured stages in the development of each piece, and 36 woodblocks made in the School of Design woodshop that showed “the potential textures, tectonics, and forms one can achieve in the shop,” with the students’ work as inspiration. The show’s curation highlighted the critical thinking, calculation, testing, problem-solving, and revision that are all part of “making things.”

The exhibition itself was designed with these ideas in mind, to evoke the fluctuations and ebb-and-flow motion of the iterative process, in the arrangement of the objects and visuals and in the layout of the space. Shifting air gently moved the hung work, for example, and a corner area invited visitors to pause and have a conversation or reflect on the work.

Jin describes the total curatorial project as “a meeting of different fields,” with four students* of interior design, industrial design, and communications design collaborating with her to realize the exhibition—together, experimenting with the core concept “of the dialogue through making [. . .] , with paper [in the exhibition booklet], with wood, and with photography, each addressing their respective field of specialty/design focus.”

In Ebb and Flow, as both an environment and a collection of works, the creation story behind our things perhaps mirrors the way we make our space in the world. “Creativity flows from the constant dialogue between the hands and the eyes, and it is not always agreeable discussions, it could be arguments, disagreement, or even temporarily unresolvable conflicts,” Jin said. “Design is the outcome of the back-and-forth decisions addressing this beautiful tension.”

The Work

The following is a selection of student works from Family of Things. Quotes are excerpts from reflections students submitted for the exhibition Ebb and Flow.

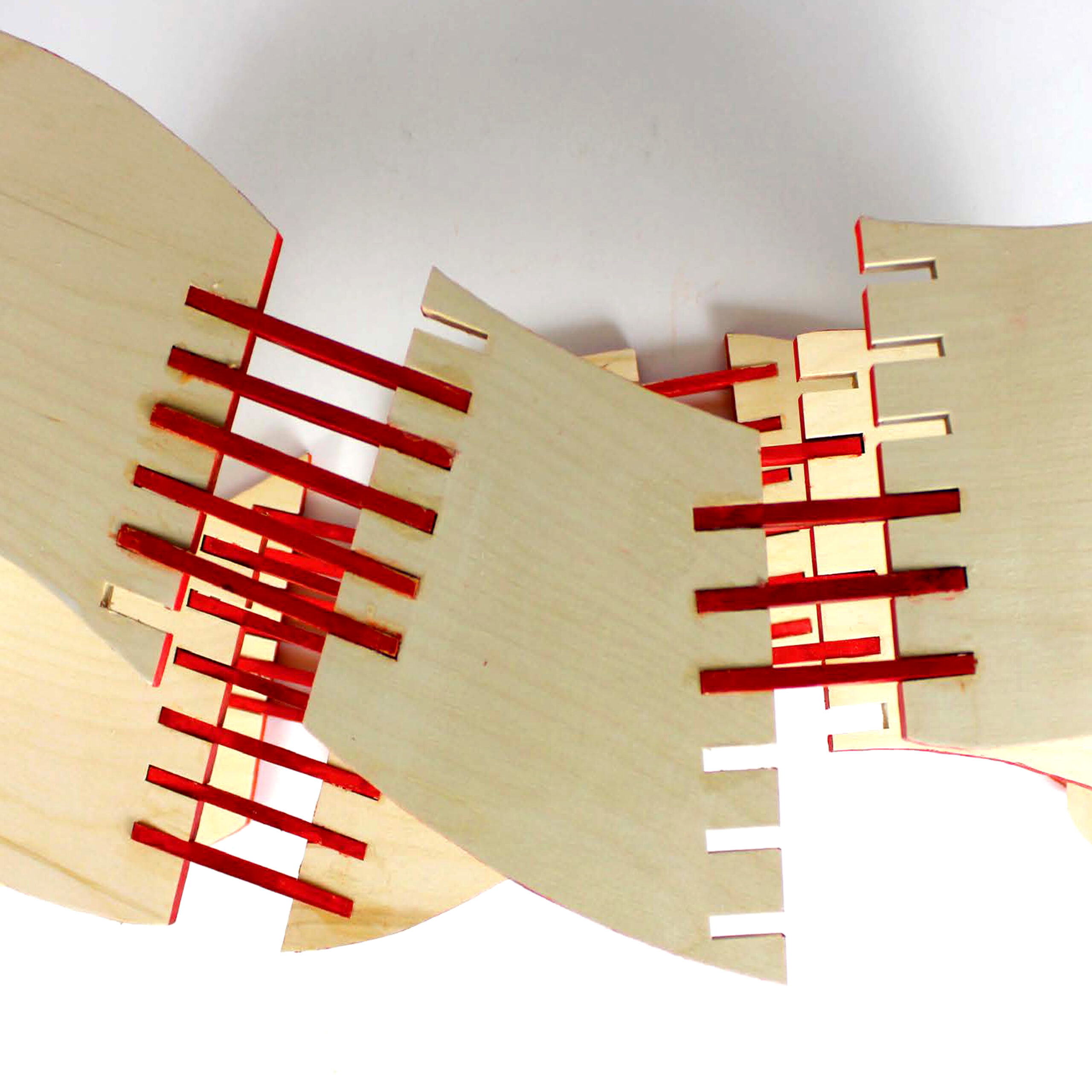

Ziqi Gao, BFA Interior Design ’22

The idea of shelf design comes from sewing fabrics, which makes me wonder how to “sew” harder materials, like wood. Therefore, I tried to connect the shelf components using stitches without touching each other. Next, I explored making a zigzag shelf. The method is to cut a notch at the end of the stitch so the components can be connected at different angles.

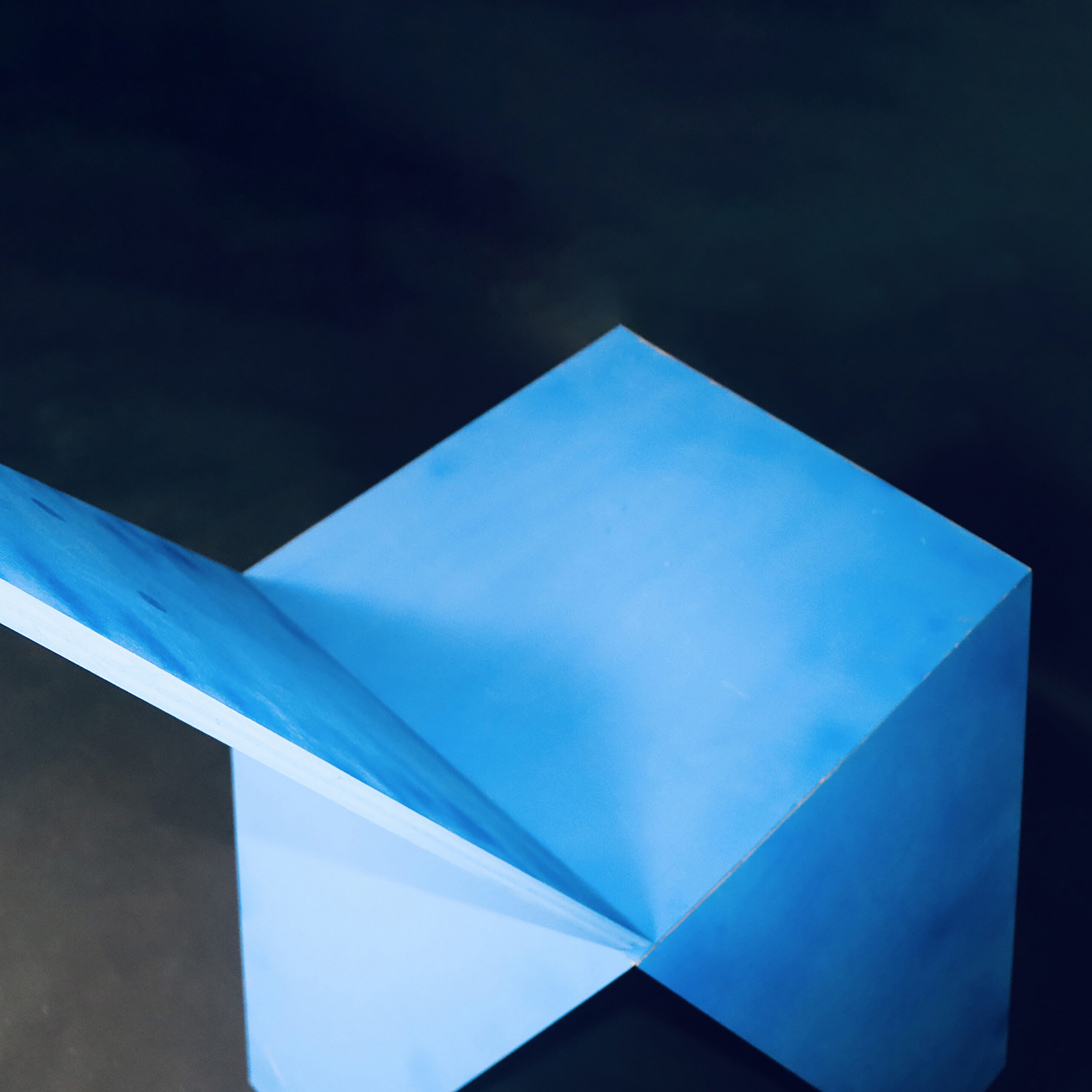

Kaelin Probeck, MFA Interior Design ’23

Thinking doing geometric designs would be an easy task when working in the shop for the first time, I focused on angled supports. However, I discovered that even the cuts that seem straightforward and simple actually take a lot of precision and calculations. After learning how to do angled cuts on the table saw and connecting everything intricately using dominos, I felt more confident about forming angles and assembling them to fit perfectly and the process became very satisfying.

Shuqi Sun, MFA Interior Design ’23

The making process is always full of surprises. The part that broke me down the most was the galloping horse leg. It differs from the other three legs in that it is laterally stressed. But I ignored the grain of the wood, which was cut in one direction when cutting. The result is that its force is perpendicular to the grain of the wood, so it breaks easily. But I didn’t realize this serious problem until it broke. The remedy I took was to use a piece of wood glued to it in the same direction as the force to increase its strength. Fortunately, I succeeded.

In fact, I also encountered many other small difficulties during the process, such as determining the order and position of the chamfer, how to cut the joint precisely, etc. This is actually a learning-by-doing process.

It’s a thousand times easier to see than to make.

It was in the process of making it that I really understood and absorbed something that I thought I had learned. What can be achieved on paper will eventually become shallow, knowing that this matter must be practiced.

Bridge Wei, MFA Interior Design ’23

This furniture design experience was more of an experiment, in my opinion. Initially, I was completely ignorant of woodworking techniques, but after half a semester of instructors and hands-on training I made some noticeable progress. What impressed me more was the furniture design and production process in the second half of the semester. A small node or the cutting of a panel, or even the purchase and splicing of wood, all posed a challenge to me, but in this difficult but interesting process, I learned a lot about woodworking skills and thinking about problems, which made me admire the craftsmanship and spirit of such craftsmen even more. Overall, it was a great experience and not just a furniture design course.

Zhenglong Yang, MFA Interior Design ’22

During the process of manual fabrication, unexpected challenges may arise; even minor issues can potentially impact the entirety of the design. Therefore, it’s crucial to remain adaptable and be able to problem solve on the fly, as unexpected complications are almost inevitable.

One effective way to anticipate potential issues is to create scaled-up or scaled-down models to test the feasibility of a design. This process allows for a deeper understanding of how parts and materials connect. Nonetheless, unforeseen situations may still arise, and one must be ready to address them.

The skills and knowledge I gained from this [class] experience have not only enabled me to bring my designs to life but have also provided me with a deeper understanding and appreciation for the artistry and craftsmanship that goes into creating furniture.

Mina Yoo, MFA Interior Design ’23

This piece [the Slit Chair] was inspired from the idea that everyone has “that chair” in their bedroom where we throw all our garments and accessories that live in the transitional space between the hamper and back into the closet.

After observing and testing various ways to join three planar surfaces together while incorporating positive and negative space within slits made for items to hang on.

The process began by creating negative space slits with a chisel [but it] proved to be difficult to create clean, linear cuts. Eventually moving on to the table saw to clean up the cuts, the downside was very apparent when the rounded edges of the table saw overcut the back side of the material.

It was very interesting to see the many ways to approach one design choice and the pros and cons to each.