It’s not uncommon for professional paths to be anything but linear. For alumna Abbey Miller, BFA Fine Arts (Sculpture and Integrated Practices) ’20, studying at Pratt Institute was not only a stage on that journey that honed lifelong skills and sensibilities but a portal to new fields of practice.

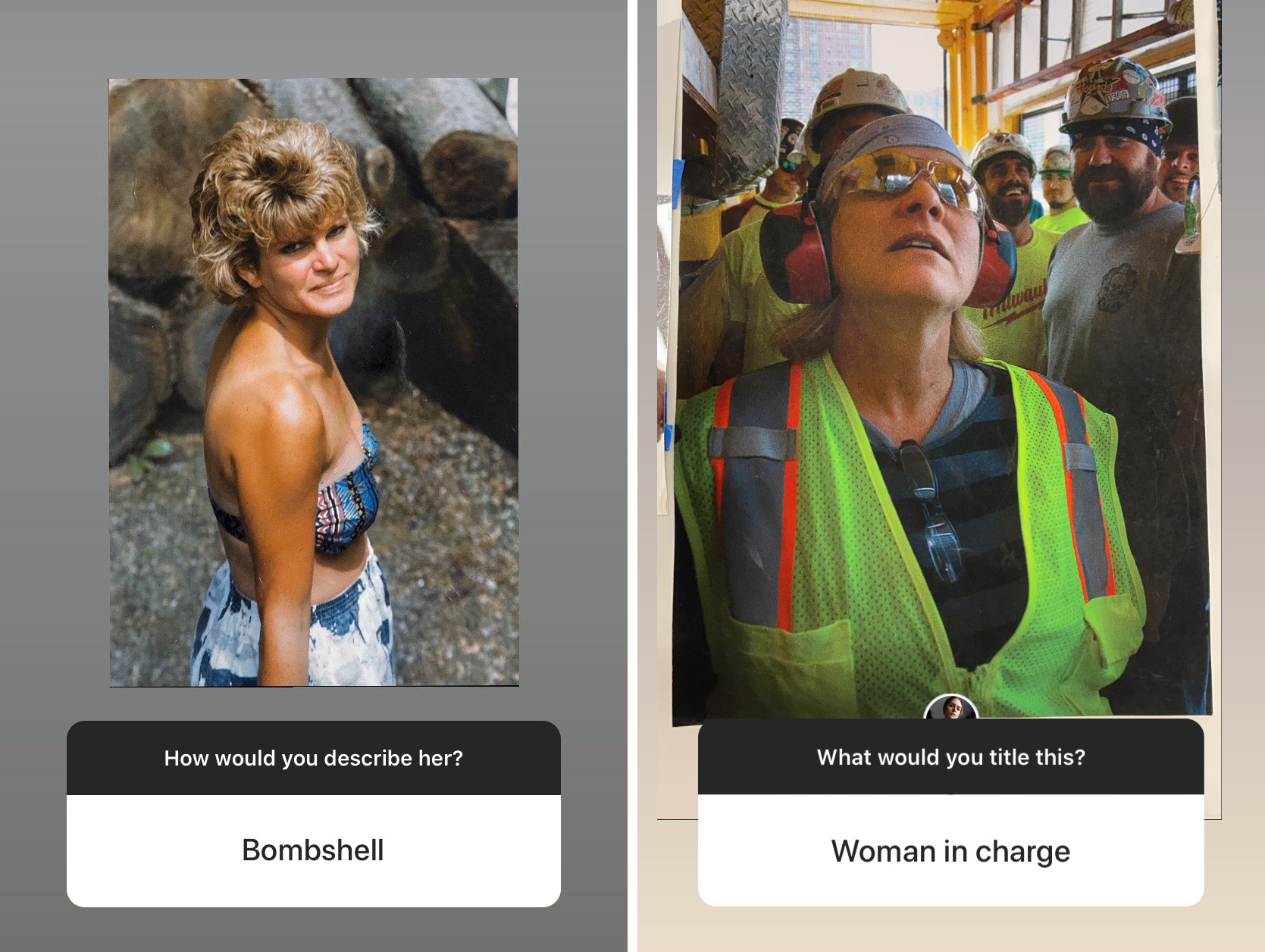

Miller came to Pratt after studying journalism, attracted to the Fine Arts major’s sculpture and integrated practices emphasis for what she calls its translatability—and her work and explorations at Pratt did serve as a springboard. After graduating, Miller made her way to scientific research, now a first-year PhD candidate in applied social and cultural psychology at Florida International University. Her research interests stem from topics she investigated as a fine arts student, including gender, sexuality, and intimate relationships in relation to perception and identity.

Along the way, Miller developed transformational relationships with several mentors, among them, Analia Segal, adjunct professor (CCE) of fine arts and coordinator of the sculpture and integrated practices emphasis, herself a doctoral candidate at Universidad Politécnica de Madrid.

At the start of the academic year, Miller and Segal sat down to discuss their ongoing mentoring relationship and research, investigation, and critical practice across disciplines.

Analia Segal: Should we start at the beginning? You and I started to work together during your junior year at Pratt.

Abbey Miller: Yes, I remember that fondly. I’ll never forget the first time I met you. It was my sophomore year—I was a transfer student, and I was still getting acquainted with Pratt culture, and art school culture. Then, in my junior year when we started working together, things really started to click for me. I felt like I had a professor who pushed me, but also gave me trust and support. I started to investigate the things that I was interested in from a more critical lens, more theory, and more research, rather than the tactile approach that had been presented to me from my earliest exposures to art. I was always passionate about whatever I was investigating, and the topics that I grew to have interest in just accumulated from there.

AS: I’m thinking about how your education in art opened up doors for critical thinking and dimensions of citizenship for you.

AM: You said this to me, and this is something that I share with my students now: your research, whatever field you are in, is a confirmation of an intuition.

I was interested in topics like sexual abuse, sexual exploitation, gender differences. But finding my voice was difficult—what I had the right to say and where I would position myself within a conversation.

We don’t choose how we come into the world, but we do get to choose where we position ourselves in the world and the conversations that we partake in, and how those conversations are enacted—by that I mean, who has a voice, what topics are discussed. My time at Pratt helped me conceptualize where to position myself, and it also helped me to understand how to listen.

“I don’t position myself as the expert, but I am the storyteller. That’s where I want my voice to be.”

Abbey Miller, BFA Fine Arts ’20

AS: So, your BFA was a catalyst that allowed you to dive deeper into subject-forming questions and ideas across and beyond disciplines. It makes me think the learning process is a quest to find a way of transforming our instincts into shareable actions. Art as a field is a place where you’re finding your voice, your drive, and understanding what you have to say and how you can contribute to what is happening in a larger cultural fabric all the time. As you’ve moved forward in your education, you chose a discipline that allows you to have a very different way of thinking about those topics—like you said, you’re still exploring similar issues.

AM: Pratt also gave me the ability to tell stories. At Pratt, that was translated in different mediums. I was a fashion minor. So I would use different [approaches] in fashion. And now as a PhD student, that’s done through research. I don’t position myself as the expert, but I am the storyteller. That’s where I want my voice to be.

AS: That notion of storytelling is an enthralling intersection of artistic and scientific research, which reminds me of Susan Sontag’s notion that we tell stories both to reveal truth but also to spark imagination.

The way that you’re describing your time at Pratt, and with your BFA, it was almost a process of unlearning. In order to find what your place is, you had to unlearn a lot of things. You gave yourself time and space for that to happen, and I think that that’s why you gained the tools to move into this new field, because you embraced that possibility.

Courtesy of Abbey Miller

As a witness of your work in those years, I believe that there was a commonality throughout your work—it has a lot to do with awareness, being in tune with perception, all kinds of perception, thinking that art can be a platform to nurture or develop that sensibility. Is that accurate?

AM: I think that if you’re doing anything, you have to question from what perspective you’re approaching that thing. I’ll speak to art and I’ll speak to psychology.

As an artist, you always have to examine your perceptions, what perspective you’re coming from. The great thing about art is that there are so many different narratives that are coexistent with each other. I like to think that they’re all equally valid, regardless of whatever social structure is pushing forward at the time.

But psychology is different. Psychology, as a field, is Westernized and white and all of the methods and epistemologies and theories that stem from that perspective cater to the people who created it. Not to say that the field hasn’t acknowledged that extremely narrow and ethnocentric viewpoint. But as somebody who came into this [PhD program], constantly questioning—who’s telling the story here, what’s at play?—I never am satisfied with the finality that one narrative is true or applicable. Science is just another way of telling a story. Whatever story is being told by the researcher or whomever, it needs to be contextual.

As I’m doing my research, I’m thinking about my role in it, and that’s why I say I’m a storyteller, I always keep that at the forefront of my mind. When I go into a project, or if I want to run a study, it’s not about my story. It’s about the participants’ stories, and theirs are the perceptions that matter.

So yes, to sum up my response, I think perception is extremely important, and it dictates literally everything that I do.

“The skills you acquire might go through a process of translation or interpretation, depending on the field that you end up making a life in, which may not necessarily be art.”

Analia Segal, Adjunct Professor (CCE) of Fine Arts

AS: Your answer speaks a little bit to a question I had about research as a process of discovery with the potential to transform knowledge and understanding of the world around us. Do you think that artistic research methods and practices that you used at Pratt were helpful and gave you tools for your PhD?

AM: Pratt gave me an endless list of skills. The creative tools, learning how to use all this different software—that is huge. Not a lot of people in my field have that. For example, I can create study stimuli. For the study that I’m doing right now, I’m researching cultural appropriation, and I had to create all of these different logos, some that were culturally appropriative and some that were not. Before I joined this program, [the researchers] would hire a designer to do it, and it cost thousands of dollars. It’s made me an asset to my peers, so I get a lot more collaborations that way—and that kind of thing builds the strength of the community that you’re in.

Also, the literature that I was exposed to during my time at Pratt has given me references to use when creating studies and material to include in my literature reviews.

The work ethic—that’s one of the biggest things. At Pratt, we all had a studio practice, and I learned how to go into the studio and create a space that is conducive to work. Which translates—my studio now is not nearly as exciting as my studio at Pratt, but it is my space, and I’ve created a sanctuary for myself where I feel inspired and excited to go every day to do my work.

So I think those are the three things I would emphasize for students today: the creative skills; the research material itself, literature, history, whatever that means; and studio practice.

Courtesy of Abbey Miller

AS: I think that’s going back to everything we have said, this idea that the skills you acquire might go through a process of translation or interpretation, depending on the field that you end up making a life in, which may not necessarily be art.

AM: When I started looking into the PhD in psychology, it just made sense. I could research the things I was interested in at Pratt, but from a scientific research lens. I actually applied twice. The first time, I applied to 13 institutions, and I didn’t get into any of them. So I had a whole year of crisis. But during that time I reached out to somebody who connected me with somebody else in the lab I am in now, the PWR Lab: Power, Women, and Relationships. I sent the principal investigator, Asia Eaton, an email and introduced myself and my background. She invited me to come to lab meetings to see if I liked it, and I was really interested in the work, so one thing led to another. I joined Dr. Eaton’s lab as a research assistant and started taking on projects—using things I learned at Pratt, like how to self-advocate and pick up new skills, DIY-ing a lot in this new field. It was fun and exciting for me, and when the next application cycle came, [Eaton] encouraged me to apply.

AS: Do you believe your education gave you the courage that’s always needed to undertake anything new for the first time? I think that art gives permission that way.

AM: It definitely gave me courage. You have to have courage to be vulnerable—and you have to make yourself vulnerable. The more vulnerable I was, to a certain degree, the greater the reward I got.

I think my vulnerability really served me when I was strategic in where I implemented it. So I have definitely been vulnerable with my mentors. I’ve opened up to my mentors in ways that I haven’t with anybody else in my life.

“I feel like the role of mentoring ripples. Students become mentors to others.”

Analia Segal, Adjunct Professor (CCE) of Fine Arts

AS: How would you describe the role of mentorship in your education and career trajectory?

AM: So, I knew I had good mentors at Pratt—you, Analia, and I also loved Carlos [Motta, associate professor of interdisciplinary practice]. I think that mentorship is absolutely critical in navigating your career or wherever it is that you want to go. You and Carlos aren’t psychologists, but you are experts in your field. To me, that expertise translates to other areas of life. And it wasn’t just mentoring me as a student. It was mentoring me as a 21-year-old. I think sometimes that was even more valuable to me than academic or career mentorship. It’s the same way with my advisor now. She does sign my paperwork, but we talk about personal things, we keep it real.

AS: The embodiment of artistic practices can be a space for sharing and a scenario to learn about how to coexist, a way of learning how to be two, paraphrasing Luce Irigaray. It also makes me think of the need to emphasize the integration of lived experiences and reciprocity, challenging old methodologies in research in order to find new ways to share it with others. You are very familiar with my approach to sculpture as a medium to write from/with the body, as well as a way of thinking about and through materials. And the significance of the classroom as a space for dialogue that is not only interdisciplinary but also intercultural.

AM: The power dynamics completely changed when I entered your and Carlos’s classes, and that was really empowering for me. It led me to trust my advisors because they trusted me.

AS: I feel like the role of mentoring ripples. Students become mentors to others. For you and me, it’s not something that stayed in an anecdotal moment in time when we connected. We keep in touch, and now you are teaching, and this conversation itself could resonate with students. So, I know that as a student, you did a lot at Pratt—you really took advantage of how rich the experience on campus can be.

“An art degree is everything. You can literally do whatever you want with it.”

Abbey Miller, BFA Fine Arts ’20

AM: You hear this in orientations, there’s a place for everybody. And there really is—and if you don’t find your niche, you can make it. That’s what’s so great about Pratt.

I was an RA, and that’s really when I started to flourish, because I felt the values of being an RA, like being organized and having practical things in check, really complemented the way that I go about my life.

I like to be outside, I like to exercise, I like to take care of myself, I like to eat healthy. This is something that is also emphasized for me now in grad school: Put yourself first. And that means developing healthy habits so you can put the energy that is required from you into whatever it is you’re pursuing. That’s advice I would give students. If you don’t know how, talk to your peers, and there are services available. Talk to people, don’t be afraid to ask for help.

There was a time when I was struggling mentally and I needed somebody to tell me to seek out a counselor. So, having a strong support system also keeps you accountable. I know it’s difficult for some people to surround themselves with people who are positive influences, but as much as you can, do that.

Don’t be afraid to be a little bold, be a little fearless, because it will serve you well. And when it comes to the translation from art to other fields—like psychology, or math, or medicine—I didn’t really understand the possibilities until I went out and did it myself. So I hope this sheds some light. An art degree is everything. You can literally do whatever you want with it.

AS: I’ve been thinking about this idea from the American cognitive psychologist Mark Runco about the creative process’s different stages and phases, which begin with orientation, intense curiosity and information gathering to define the problem, and processing information. I think the BFA degree as practice-as-research gives you orientation and incubation for your ideas, and then they can link to what’s next, bringing work out into the world in different ways.

AM: One more thing is that I’m dedicated in my practice, in my research, to not keeping fields so compartmentalized, so having this conversation—besides the fact that it’s fun, I love to see you—it’s a huge aspect of my work. For my dissertation, I want to find a way to include artists or artist communities in science, so that door is always open. And if I can help students, I’m always here. I’m a resource, so use me.

AS: Just to finalize this discussion of mentorship, I thank you for your trust—I think that it’s vital to sustain relationships throughout time. It’s this idea that you’re net weaving, you’re creating rafts facilitating circulation and connection throughout your life, and they move, they don’t stay at Pratt.