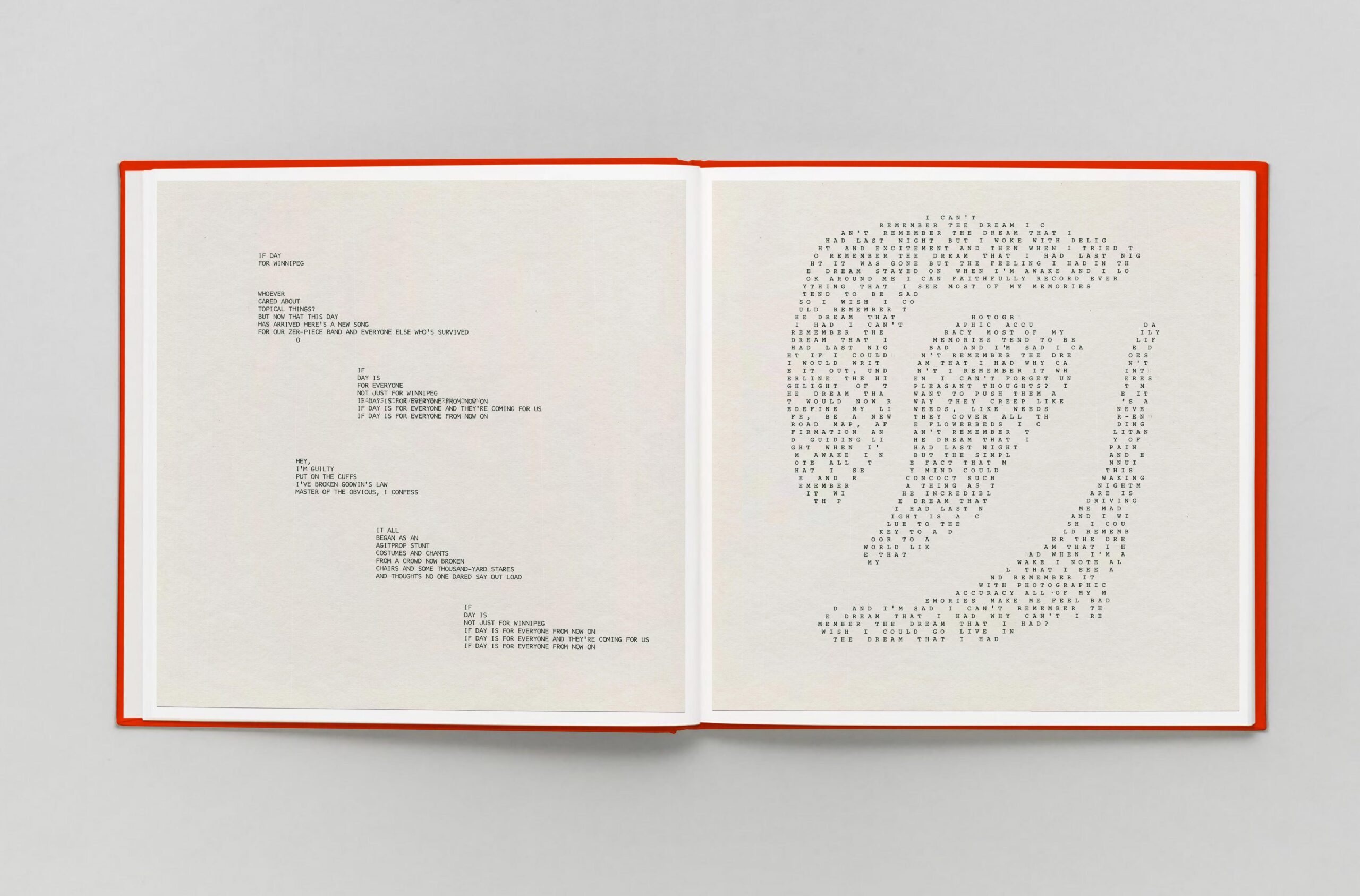

John Flansburgh, BFA Fine Arts (Printmaking) ’84, and his longtime collaborator John Linnell never put a limit on their creative vision. As the songwriters behind the rock band They Might Be Giants, the duo has created a unique strain of eclectic pop music that, since 1982, has earned them two Grammys and a Tony nomination. The band has galvanized listeners with their unconventional sensibility, nesting their songs in colorful live performances, offbeat album designs, and carefully considered music videos that, in Flansburgh’s words, have functioned as “a frame around the whole project.” With the release of BOOK in 2021, the band combined their wide-ranging interests, bringing lyrics from their recent records into a photo-filled, playfully designed art book and an original musical album.

Much of They Might Be Giants’ multifaceted creative approach can be traced back to Flansburgh’s time as a printmaking major at Pratt Institute in the early ’80s (he graduated with honors in 1984). Flansburgh produced the band’s earliest flyers in Pratt’s printmaking facilities, and his fine arts education not only gave him tools to shape the identity of his band but also informed his practice as a musician. For many of They Might Be Giants’ early innovations in music making and distribution—from their performative live shows to their playful Dial-a-Song service, which listeners could call for a new song from the band each day, and which was run out of the apartment Flansburgh lived in while attending Pratt—Flansburgh’s explorations as a student artist served as a key influence.

Following the release of BOOK, Prattfolio spoke to Flansburgh about finding a dedicated cult audience and how the wisdom gained at Pratt has stayed with him throughout his multifaceted artistic career. (This interview has been edited and condensed.)

During your time at Pratt, you balanced your studies with an organic music-making practice with your They Might Be Giants bandmate and then-roommate, John Linnell. How did your student experience influence you as an artist today?

John Flansburgh: I learned an incredible amount from the printmaking program at Pratt, and Foundation year was important to me as a musician because it taught me how to be rigorous with materials. It taught me that if you try to do 10 things in a day, one of them might be interesting, and sometimes that’s better than working on one thing that’s not interesting. That helped me unlock a lot of the mysteries of how to be a creative, productive person.

Also, the first week I was at Pratt I started drinking coffee for the first time, which was a total life changer for me. All of a sudden I had a lot of ideas and I talked really fast. I became a different person, it transformed my life and personality. I recommend it to everyone.

Did you find your academic pursuits and your work on They Might Be Giants informed one another?

JF: I ended up concentrating in printmaking and making a lot of monotypes. Even though you have all day to do it—you can fix things and change things—that way of having at it in a single session was a very transferable skill for writing a song. There are things that I’ve learned about songwriting that help, like the importance of starting a song and trying to finish it the same day. I feel like working at Pratt taught me that if you crack something open and it’s working, it’s nice to get as much out of yourself as you possibly can in that first blast.

You’ve talked about having to overcome the perception of being labeled “quirky” or “comedy rock” early in your career. Did your education prepare you to match the playfulness of the band’s roots with the rigor of an artistic life, and if so, how?

JF: While I was at Pratt, everyone was preoccupied with issues of authenticity. At the same time, the East Village art scene was blowing up, and that was maniacally un-obsessed with authenticity. It seemed more obsessed with veneer, surface, and 24-hour party people.

When we first started, we were playing in clubs, so everything was theatrical, and everything was in the moment. The immediacy of the humor and the songs actually helped us connect and pull the audience into our shows. When we started making records on the Dial-a-Song [telephone service in 1982], it wasn’t that different from our early live shows. We knew people were just hearing the song one time; they weren’t necessarily calling back again and again. There were a lot of things early on that supported a sensationalistic way of working.

But when we started making recordings, we were smart enough to know that we wanted to do something that would hold up a little bit better, and we made some big adjustments in how we arranged the songs to not have them be too cloying.

It’s hard to explain, because almost all good dramas have tons of humor in them, but if you’re writing a song that has some humorous element and it’s too over the top, that ends up being corrosive. It stops listeners from being able to hear the song again and again because it just wears them out. There’s a lightness to most great music, but things that have any kind of comical element are rarer.

You’ve said that telling your parents you’re becoming a full-time rock musician can feel akin to telling them you’ve joined the circus . . .

JF: It’s not a great day with the parents when you tell them that you’ve decided to ruin your life! To be perfectly honest, I don’t think my mother, who has been very supportive in overt ways, thought there was anything so fantastic about me being in a band until we won a Grammy. That was something that she could mention to her friends, and they would be like, “Oh, that’s good! He’s an actual professional,” because nothing we were doing showed up in her world, except maybe when we were on NPR shows.

What as an artist helped you to break out of those preconceived notions of precarity to carve a sustainable path and become the artist you are today?

JF: Our audience has been tremendous in supporting our project. But not just in a “hit song” way. They’re as curious about our left-field work as they are about songs that sound like radio singles. And that’s not always the case.

There’s this thing that I’ve seen happen to all sorts of other bands that never happened to us, where they burned very brightly and were much more commercially successful the moment that they broke as a band. And then in just as surprising a way, the culture said, “We don’t want to think about your band anymore.” If that had happened to us, I don’t think we would have been able to go on, and I’m so grateful it never did.

John and I also have been pretty dogged about just keeping on going. A lot of people burn themselves out and get tired of doing the same kinds of things over and over again. There’ve been some ups and downs, but by and large, we’ve never had to start again. We’ve just been going.

You called the band “our project,” and have said that you see They Might Be Giants as an extended art project. How have you sustained this sort of fluid creative vision for over 40 years? How does BOOK build on that vision?

JF: To me, if you’re in a rock band, the way you package your work is a big part of what you’re presenting. The album cover isn’t just an advertisement for the album. At its best, it’s like a frame around the whole project. Learning how to collaborate with other people on this project, for me, has been rewarding because it’s allowed the scope of the band as a packaged thing to kind of blossom.

John [Linnell] and I have extended our collaboration to working with a backing band, and we also work with graphic designers and photographers and video makers and all sorts of people. We work with Paul Sahre, who is the graphic designer who worked on BOOK and who we’ve done a lot of projects with over the last 10 years. It’s really interesting, finding a way to describe what we’re doing musically and having it be turned into a visual thing. It’s nice to be able to work with other people who take the work to a different level. It’s fun seeing people make cartoons out of your songs too!

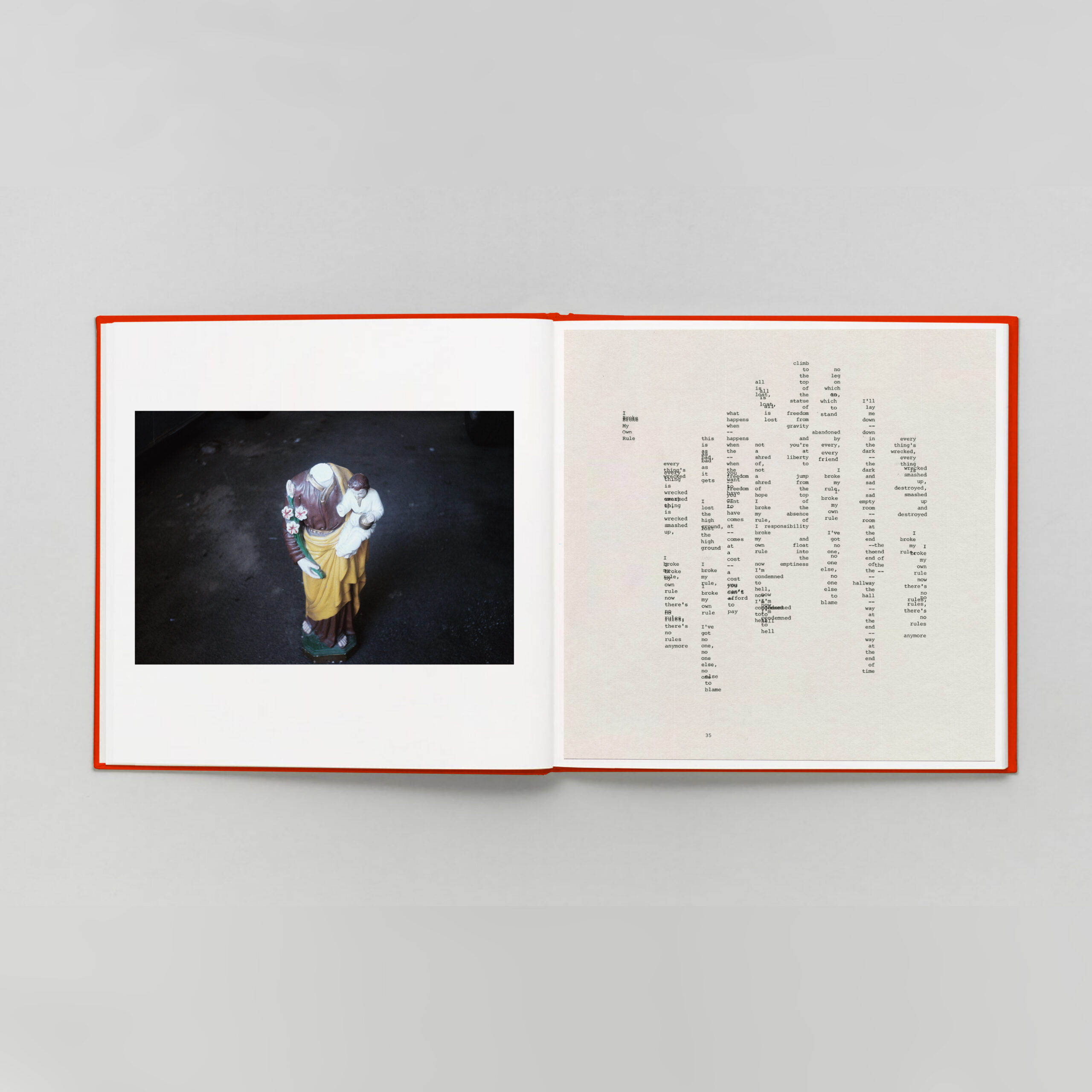

How did you connect with Brian Karlsson, who’s also a Pratt alumnus?

JF: I started working with Brian completely long distance, on cell phone calls and emails [during the pandemic]. Paul Sahre knows somebody in the photography world at Pratt who had a bunch of connections with up-and-coming photographers there, and Brian Karlsson’s work stood out, in part because it was street photography. There’s something kind of egoless about street photography that’s fascinating to me—there are so many different ways street photography lands in the viewer’s mind. If you think about Diane Arbus or Robert Frank, or even Margaret Bourke-White, you can connect with the photographer’s way of seeing the world, but everything also has this one element of remove.

Somehow, that spoke to me, and it connected with the kind of writing that John and I are doing. So it was a very easy decision to make all the photographs in BOOK Karlsson’s work.

I still have yet to meet Brian Karlsson! It’s really weird. I owe him at least one meal in an overpriced restaurant.

What’s one thing you would recommend everyone do on or around Pratt’s campus, whether or not that recommendation still exists?

JF: I’ve always found the structure of the library fascinating. Going inside the library, with the way the cases work through the stories of the floors is kind of remarkable. It’s from that era of architecture when a lot of steel, iron, and glass were being incorporated. That kind of architecture—like the Eiffel Tower, Grand Central—I love, and the library at Pratt is a really good example for me.

Is there any advice you would give young people coming up in art or music making today?

JF: I had a professor who taught color at Pratt who said, “Being an artist is just foisting your obsessions on the world.” I think he was being flip, but I have to say, I think there’s a large element of truth to that because it has to be your goal in a way. If that’s not good enough, if you don’t feel like you’re making a strong enough impression, I don’t know if you’ll ever be satisfied working in a creative field. You have to feel like you’re getting your ideas acknowledged.

I’m reluctant to give advice to people because what people want out of it is so different. I would just anticipate the worst, and get all the pleasure out of it that you possibly can.