When Prattfolio was planning the Summer 2021 issue on the theme of Care, we asked Pratt students and faculty in an email survey how care was influencing their work.

Who and what needed particular care in this moment? How were projects and initiatives responding to challenges to well-being and confronting the immediacy of what might have once felt like distant, abstract crises? What tactics were helping artists, designers, scholars, and educators shape the future? Here is a snapshot of care in the work coming out of Pratt from the responses we received.

For some students, the events of the past year underscored the need for repairing social the fabric and supporting the health of communities as well as tending to the individual body and mind.

Layers of care from the personal to the communal, physical to psychological, intersect in the degree project of Ida Marie Hansen, BArch ’21. In this current moment of pandemic-constrained connectedness, her speculative provocation, titled Soft Order: the Squishscape Residence, examined how social distancing and its “touch deficit” effects might inform an architecture that offers tenderness.

Hansen shared that she developed this concept for a coliving space, winner of Undergraduate Architecture Degree Project Design Award 2021, in an architecture studio focused on psychosocial densities—“considering how changing dynamics impact how we see future ways of organizing,” in her words. In the project, which engaged with feminist discourse around care and maintenance as well as theory on the body, “architecture becomes a surrogate caretaker, providing hugs, wombs, and spaces for joint acts of maintenance and care.”

In addition to the tactile experience, Hansen, who graduated with a minor in social justice/social practice, also explored ideas around cooperative living and its implications for collective care. This emerged from research on single-occupancy apartments and seclusion and loneliness in relation to larger social structures. In Soft Order, “the lonely occupant, and especially the young person who may feel like they can only build a future of permanent belonging through hierarchical relationships, is centered as interdependency is encouraged.”

Hansen also recommended the project of her fellow winner of this year’s Undergraduate Architecture Degree Project Design Award, Onyinyechi Egbochue. Sited in West Oakland, California, Egbochue’s project Seeded Junktion: Healing Earthself addresses issues residents grapple with daily—namely food insecurity and the effects of a profound wealth gap generated by the tech economy’s boom in the region—with a framework for healing.

“For many members from marginalized communities, taking time to heal from generational trauma, ancestral trauma, and internal trauma is one of the most powerful things we can do with our physical time here on Earth,” Egbochue wrote in the project presentation. “Healing, or self-preservation, is an active and revolutionary form of resistance.”

Seeded Junktion takes a playful approach to restoring connection among people and their environment, inspired by the cultural energy of West Oakland, imagining a space where members of the community might reclaim agency and find flourishing. “Seeded Junktion is a guide for food and land sovereignty,” Egobuche explains, “envisioning a future where humankind and the earth are allowed rest and recovery from current destructive practices.”

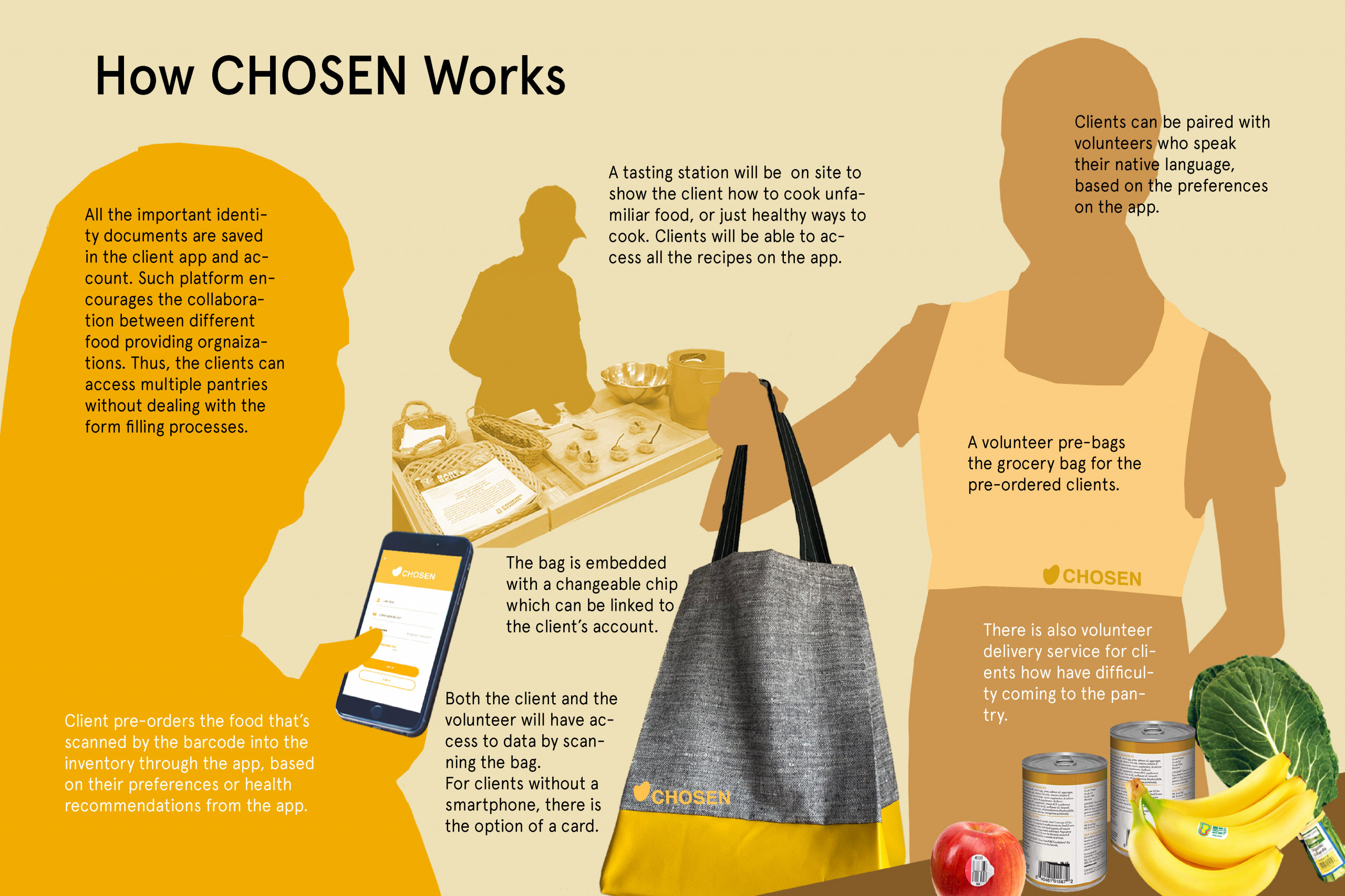

Before the pandemic, Ellen Zhengyi Ren, BID ’21, had spent time volunteering at soup kitchens and food pantries in the city. Through these experiences, she came to understand the nuances of care that services like these can offer individuals who rely upon them, for not only nutrition but often person-to-person connection as well.

“When I was volunteering,” Ren wrote, “one staff worker said to me: ‘Say hi and talk to [the clients]; this might be all the love they’ll get this week.’ This quote stayed with me ever since, and it inspired me to dig deeper into the matter and try to make the food pantry experience better for the people who need it. This created an opportunity to recognize and reinforce a sense of community through more human interactions and individual care.”

With her award-nominated project Chosen, Ren sought to further humanize the pantry pickup process, through a system aiming to shorten wait times and ease access to healthy and nutritious food. During the pandemic, she notes, care for people experiencing food insecurity—whose numbers may have increased in 2020 due to COVID-19—faced significant hurdles as cities locked down. But some groups were able to adapt and make service even more personal, delivering directly to people’s doorsteps, based on the energy and coordination of volunteers, which Ren found inspiring on a number of levels.

“As a designer, I feel that their care and dedication is something we can definitely learn from and add to our own works,” she wrote, also pointing to listening as key. “I have experienced myself when a seemingly brilliant idea turns out to amplify the problem I was trying to solve. My tactic to avoid this situation is to talk to the users early in your process, through as many methods as you can, such as interviews, surveys, and observations.”

Listening has been central too to Dana Hinkson, BFA Communications Design ’23, who found herself asking about the impact of her design at this transformational time. One of the questions that came up in her creative process was “would this cheer someone up?”—and to find out, she made it a practice to gather various perspectives.

One of the listening tactics she has used is getting a group together for a “think tank.” “Having a think tank allows me to hear multiple perceptions of the problem and different solutions,” she said. “The synthesis of those problems and solutions is how I put everything into perspective and find an impactful solution that can benefit as many people as I can.”

To Catherine Chattergoon, a third-year undergraduate architecture major with a minor in social justice/social practice, care is an action word. “This year has been a clear display of the harm of systemic injustice, and if we do not have systems that exert care, we must become the systems we need to change our world,” she wrote. “Art and design have the potential to help us see the world from a different point of view, and I believe that caring can change everything.”

Chattergoon describes approaching her work from a place of care—work that extends from the studio into the Pratt campus community—and she sees compassion as fundamental to its impact. “The heart of architecture lies in connection; it fosters communication and shapes relationships in the built environment,” she said. “Architecture needs to be rooted in care, because we have to be in touch with the complexities of life and how we impact them through our work. . . . I believe in the potential and possibilities of the future; through participatory practices and collective care, we can create equitable futures that can be designed into existence.”

Danni Qu, BFA Communications Design (Illustration) ’21, also centered care in and outside of the studio during her time at Pratt. With a minor in psychology, Qu established a chapter of Active Minds, a mental health awareness club for students, at Pratt. When she became president of the Student Government last academic year, Qu prioritized mental health. For example, with students who were active on campus in mind, she organized a care package campaign with items that could aid in calming, destressing, and feeling connected to one another—items like ear plugs, a sleep mask, and a journal, as well as a letter from her and postcards featuring fellow students’ work from across disciplines.

In her design work, Qu took another approach to centering young people’s mental health with her thesis, Land der Heilung (Land of Healing), a digital therapeutic space. “What I’ve learned is that due to everyday restrictions (on gathering and traveling, mainly) from quarantine, these communities are reaching out more to crisis and mental health support,” Qu shared. “I want to provide a point of entry into a fun, fictitious space where they can relax from the often suffocating feeling of being in the same (and often unfavorable) space for long periods of time. I want to make aware of the type of disconnection one often feels during daily digitized interactions, thus examining how we can break traditional methods of storytelling, digital accessibility, and advocating for mental health wellbeing. I believe there is a lot of potential for this type of integrative practice.”

Elliot Lovegrove, MFA Fine Arts ’22, wrote about how he has seen art making entwining with giving and community care in his practice and others’. “The arts have a long history of being used in ways which run counter to care: wartime propaganda, lavish displays of wealth to maintain power, exhibitions that flaunt technical virtuosity or (perceived) intellectual superiority,” he said. “But there’s another side to artistry and to making—also with deep roots—which is intimately intertwined with care: making a wedding gift for a good friend, or staging and decorating for a banquet to honor a community leader, or preparing a meal for guests, which communicates welcome and celebration.”

Lovegrove found that energy of connection and exchange running through his recent work that incorporates the art of shuttle tatting, a form of lacemaking he learned from his grandmother. “During the first year of my MFA [in 2019], I finally worked out how to integrate tatting with painting,” the medium in which he is trained. “I felt the pull to give away the practice objects I made,” he said. “I tatted on the subway, and in the home I was staying in, and with my classmates as we sat in the auditorium waiting for guest lectures to start. I think the slow, repetitive nature of so many fibers techniques lends itself to these kinds of occasions—and the personal interactions that accompany them. It also means that an excellent or impressive end product often demonstrates commitment more than a stroke of genius, making it a great vehicle for communicating personal value and care.”

These moments of reciprocity have opened up new depths of meaning in Lovegrove’s practice. “As I work on my (formal, gallery-oriented) pieces using tatting,” he wrote, “I’m furthering a real-life connection with my grandma, and hearing about other people’s relatives which the pieces bring to mind, and getting input from strangers on the subway, and starting to become acquainted with the extraordinary community that’s gathered around lacemaking. For me, that’s all valuable—that’s where a lot of the care happens. Learning how to practice art in a way that not only builds on all of that, but generates it, has been one of the biggest gifts and developments for me as an artist.”

Care embedded in materials and practices is also at the center of work by Marissa Giordano, BFA Fashion Design ’21, who wrote about the thoughts behind her fabric choices as well as design concepts. Her process begins with vintage and second-hand garments and deadstock fabric, sourced as a way of responding to high-speed production processes and waste within the fashion industry. Giordano then reshapes these pieces into gestural forms that engage with the ideas around personal stories and our penchant for reinvention, “the eras we go through as people.”

“Sustainability is what I feel needs particular attention and care right now,” she wrote. “All of my garments are androgynous pieces so that they can fit on many bodies in order to continue with the theme of passing down garments and the longterm investment you make in the clothes you wear (both emotionally and physically).”

While she keeps the future in mind, attention and care to an upcycled piece’s origins is also part of Giordano’s thinking. “To deconstruct and reconstruct its form shows the care for the traditional garment it once was as well as how the finishes warp its initial purpose into a more artistic expression of what a garment can become.”

Melissa Chua, a Master of Architecture candidate, has been exploring how space and sound can activate healing. Last year, Chua received support from the Pratt Graduate Student Engagement Fund to develop the Healing Spaces Project, with a podcast in the works as well as a book and physical space prototypes that could activate once society emerges from the pandemic.

Among the healing approaches Chua’s project explores are meditations, breathwork techniques, and insights from thought leaders in care and healing. The project has also formed beta groups for healing and coaching, to “give makers a safe space to shape new ideas and gain feedback in a supportive, intimate environment.”

“A greater emphasis on care begins with an openness to feeling,” Chua wrote. “The meditative, somatic, musical and architectural works of mine that are well-received are those that are conceived with a care for organic exploration and a freedom from linear dimensions and timelines. By shifting our collective mindset from one that strictly values productivity to one that cultivates a care for one another and a championing of unique paths, we can create a more open, less restrained world where ideas can flow and healthy relationships can flourish.”

Jahnavi Nirmal, a graduate student working in interactive arts, noted “it has been extremely important to indulge in self care in these times.” As the chaos and unrest of the world persists, brought into immediate proximity to all of us during the pandemic, anxiety and fear can be daily experiences. “It is important to take a break and be hopeful,” Nirmal said.

This outlook influenced Exhale Positivity, an interactive installation that generates visuals with positive messages when visitors activate a sensor with their breath. Understanding that in the current moment, breath has become a site of concern, Nirmal developed a remote version that sends visuals in real time through a browser accessed at home.

Jahnavi Nirmal’s installation, Exhale Positivity, was conceived for in-person and virtual audiences to experience moments of pause.

Nirmal got help filming the installation from fellow graduate student Raunak Jangid, who also shared recent work in response to our care survey. (Jangid assisted with digital production on this issue of Prattfolio through his role in Digital Communications at Pratt.)

Jangid is currently studying in Pratt’s MS Information Experience Design program. He described moving to the US from India in January 2020, excited to explore a new country, attend classes, meet new people, and take in all the new experiences he knew awaited him in this uncharted territory.

When the stay-at-home order was put in place last spring, shortly after Jangid’s birthday, disappointment hit hard. “This change of lifestyle also affected my work, habits, and diet,” he wrote. Though he started exercising, meditating, and following a diet, and made sure keeping in daily touch with family was part of his routine, but things still felt off kilter. “Even though I was trying to take care of myself, it was never reflecting. I wanted to speak out my emotions and let the world know how I was feeling.”

Jangid started creating a video series and posting the installments on Instagram. “Since my childhood, illustration is something that eases me,” Jangid said. “That is how I take care of myself—letting my feelings out through illustrations. This practice has also had a positive impact on my personal life, be it work, relations, or friendships.”

In those first months of the pandemic, Jangid knew others were feeling similar emotions, separate physically but linked on a human level. “This [project] made me connect with them on a mutual feeling,” he shared. “And this is how I started to take care of my emotional well-being.”

Raunak Jangid’s animation considers the return of unexpected and transformational sensations: “What is that first kiss after the lockdown going to feel like? Will it be like the rain in the desert or the first bloom in spring?”

Alex Montes, BFA Digital Arts (2-D Animation) ’24, who described the respect and kindness they value in their own and others’ practices, reflected on how the past year has put things in perspective. “I’ve learned that we shouldn’t take things for granted, and we should put care into everything we do, since we’ve learned that things can be taken away at any point,” Montes wrote. “It’s caused me to take a minute to think about and make the most of even the little things. A tactic I have put to use is being more mindful of the world around me.”

Acknowledging where we are and what we are experiencing has been central to recent work by Linda Lauro-Lazin, MFA Fine Arts ’17, assistant chair of digital arts and a professor in the department, who shared two projects that confront care and loss, personally and collectively. One of them, Ordinary Reliquaries, was shown earlier this year in the exhibition The Vision of Care, curated by Robert Shane and organized by the Woodstock Art Gallery and Museum to bring together work that highlights the role art plays in maintaining and restoring the world.

Ordinary Reliquaries holds the presence of a beloved person, specifically Lauro-Lazin’s late father, in objects suspended in time and space. “When my father was in hospice, I was with him every day. I cared for him. I helped him with the most ordinary activities (just as he had done for me),” she wrote. “I made these sculptures at Urban Glass in Brooklyn in the months immediately after my father passed. The objects frozen in glass refer to ephemerality and connection through the familiar. The ice-like vessel holds a barely visible final message. The real objects aren’t there. The cast glass is simply empty where the objects would be.”

Another memorial work by Lauro-Lazin, Floating Grace, addresses the ongoing experience of the pandemic with lanterns containing words from people around the world and rituals of their lighting and release on rivers in the Hudson Valley.

The very act of teaching—the art of teaching—is a practice of care itself, and it manifests in a special way at Pratt as the liberal arts intersect with art and design practice. Longtime English and Humanities and Media Studies Department professor Liza Williams, who will be retiring at the end of 2021 after four decades of teaching first-year students, reached out to share how she cherished the honest, enthusiastic, trusting, and often enduring exchanges with her artist students.

“One of the main things I found was that students needed to be heard: that listening was my fundamental responsibility and gift to them,” she wrote. In return, they entrusted her with their written work, “creative, searching, and articulate—and I’ve had ongoing correspondence with many of them since they’ve graduated.”

“Lately I had been organizing my class around experimentation in different writing genres, along the lines of their work in different art genres. This was invigorating for them as writers and me as their ‘stranger-reader.’ They made ‘booklets’ of their finished work, and I treasure the examples they have left me. In that way, I have cared for them, and they have cared for me. Pratt students are quite astonishing in every way.”

For Amanda Huynh 黃珮詩, assistant professor of industrial design, that extra care has meant meeting students where they are. “I’ve always tried to do that in teaching, but in virtual studios, ‘where the students are at’ includes their timezone, the level of lockdown they are experiencing locally, their family obligations, all of it. It’s allowed us to see more of who they are while also being vulnerable ourselves.”

Huynh’s professional practice and research in food design, within an industrial design context, is rooted in care. This, she said, has enabled her to engage with students to imagine a future whose conditions diverge from those we have left behind. “It allows me to discuss deeper issues with my students: issues of environmental racism, access and ability, and the climate crisis,” she wrote. “We hold powerful tools as designers and cannot afford to lose this moment in a misguided attempt to preserve the pre-pandemic routine.”

Huynh shared a concrete exercise she used to help students access that future-oriented frame of mind and invigorate their creativity when “where they are” is also at a challenging point in their process. “I adapted a design exercise to become Future 8s, sketching 8 possibilities over 8 minutes,” she said. “When we found ourselves in a mid-semester rut (what I came to refer to as the ‘Wednesday of the semester’), we kicked off the class with this exercise, and I could feel the energy shift to positivity. What would your project look like in 2031? In a socialist future? What if you could only produce an edible solution? What does your project look like when designed for a six-year-old? The students started to see that I was not limiting them to the current context and the future is far more open.”

Kent Hikida, AIA, associate professor of construction management in the School of Architecture, wrote that his work across roles has focused more than ever on care this past year and a half. “The work of an architect and construction manager is to design and build the physical environments where we spend 90 percent of our time living and working,” he said. “Our focus has always been on the health and well being of the occupants, social justice, and environmental sustainability; and this was emphasized during the past year of the COVID-19 global pandemic and the social upheaval following the murder of George Floyd. As an architect, I worked with my clients to modify their existing spaces to meet the ever-changing Center for Disease Control (CDC) state and local guidelines during COVID-19. As an educator, I modified teaching plans to deliver quality content to support our student learning outcomes online, and to include units on diversity, equity, and inclusion with the profession, and sustainability, which will continue to be included in the course content.”

Hikida emphasized how impactful care starts on a personal level and then extends out. One tactic he used last year during online learning sessions, to positive reviews at evaluation time: posing a question of the day. Opening with questions like what is your favorite ice cream flavor or what is your favorite film was a way of warming everyone up for meaningful work. One-on-one meetings were also invaluable. “This allowed us to develop stronger student-teacher relationships,” he said, “and to build [students’] confidence and skills of self-advocacy outside of the social arena of the full class.”

Those feelings of agency can have a ripple effect. “In architecture, design and construction, and education, our focus on care directly affects the quality of life in the world,” Hikida wrote. “Designing and building healthy spaces promotes well-being for our occupants; and teaching design and construction professionals to be empathetic characters who do well and do good promotes a virtuous cycle of greater caring that embodies the meaning of [the Hebrew phrase] ‘tikkun olam,’ or ‘repair of the world.’”